Using Homework as a Formative Assessment

The role of assessments in education is well-known, but when it comes to formative assessments, particularly in the context of homework, educators' perspectives vary. When using homework as a formative assessment, we enter into the debate surrounding grading homework and its role as a formative assessment tool.

While some argue that formative assessments should not be graded, others emphasize the importance of homework in fostering student mastery. Striking a balance between various assessment forms, from formative to summative, is crucial for effective teaching and learning. Explore the significance of formative assessments and homework in shaping students' academic success and future habits.

Using homework as a formative assessment

Katy Dyer in a post on NWEA—Homework as Formative Assessment—took the position that homework cannot be graded if a teacher wants to use it as a formative assessment. “Formative assessment is not for grading,” adding later, “To say that all homework is formative assessment only depends on the assignment being given and how the teacher uses homework.”

Here’s what Grant Wiggins said in Using Homework as a Formative Assessment :

In short, no matter the pure definition, I don’t think it is accurate to say that formative assessments can’t ever be graded. What matters – what makes a formative assessment formative – is whether I have a chance to get and use feedback in a later version of the ‘same’ performance. It’s only formative if it is ongoing; it’s only summative if it is the final chance, the ‘summing up’ of student performance.

Graded or not, homework is an ideal practice space for student mastery. Teachers can use this space (evaluated or evaluation-free) as a way to see daily student progress.

But can all the assessment forms be balanced or mixed to a certain degree?

Turning student practice into a “Next Generation Assessment”

It’s fair to say that there is a limitation, right wall, when it comes to testing. Finding the right balance of summative and formative assessments is complicated—but perhaps it’s not out of the question particularly when it comes to Standards-Based Instruction. Gee Kin Chou , in Quelling the Controversy Over Technology and Student Testing , mentioned one approach to balancing of assessments—yet admitted it could lead to more testing:

Attendees at NCSA 2014 spoke of a ‘balanced assessment system’ comprised of frequent formative assessments to inform teaching, a few interim assessments throughout the year to check alignment with standards, and the annual summative assessment for accountability.

Gee Kin Chou hints toward the future of assessments, augmented by technology, where the boundaries of summative and formative assessment just may become obscured.

The potential to blend instruction with both formative and summative assessments into one continuous process that engages the student…The cautious hope among many NCSA 2014 attendees is that technology eventually will enable assessments to be fully integrated into instruction, and students will neither know nor care whether the activity is being “graded”; they will just be learning.

It’s fair to say that the future of all assessments is still unknown. What about just looking at formative assessments for what they are?

Why formative assessments & homework matter

Putting more effort into formative assessments seems to be the right approach to take (whether homework is leveraged in the process or not). The question then becomes this: What are the sources of formative assessments and how should we value them?

In a 2006 study , Harris Cooper , a professor of psychology and director of Duke’s Program in Education, reviewed over 60 research studies on homework between 1987 and 2003. He concluded that homework undoubtedly has a positive effect on student achievement and overall success in school. “With only rare exception, the relationship between the amount of homework students do and their achievement outcomes was found to be positive and statistically significant.”

While this may be true, giving students too much homework can be detrimental. Students tend to get burned out and any correlation between homework and higher grades may be diminished.

No matter how technology influences the future of assessments—from formative to interim to summative—it’s clear that all forms of assessment matter and so does homework. Finding the right balance of mixing assessments, and making students responsible for meaningful and balanced homework assignments, seems to be the right approach to take.

And for anyone still skeptical about homework, here’s how Sew Ali at Edudemic, in Why Homework Matters, puts it:

So, even if you don’t buy into the fact that homework will make a child a higher academic achiever in the short term (even though research states otherwise), realize that it just might create a human being with good habits, a rich work ethic, and a success later on in the world outside academia .

Jump to a Section

Contributors, subscribe to our newsletter, related reading.

Join our newsletter

- Schools & Districts

- Integrations

- Pear Assessment

- Pear Practice

- Pear Deck Tutor

- Success Stories

- Advocacy Program

- Resource Center

- Help Center

- Plans & Pricing

- Product Updates

- Security Reporting Program

- Website Terms

- Website Privacy Policy

- Product Terms

- Product Privacy Policy

- Privacy & Trust

- California Residents Notice

Homework: A Few Practice Arrows

What is formative assessment, homework as rehearsal, grading practices, clearer communication, the case for formative assessment.

Premium Resource

O'Connor, K. (2002). How to grade for learning: Linking grades to standards . Glenview, IL: Pearson Education.

Stiggins, R., Arter, J., Chappuis, J., & Chappuis, S. (2004). Classroom assessment for learning: Doing it right—Using it well . Portland, OR: Assessment Training Institute.

ASCD is a community dedicated to educators' professional growth and well-being.

Let us help you put your vision into action., from our issue.

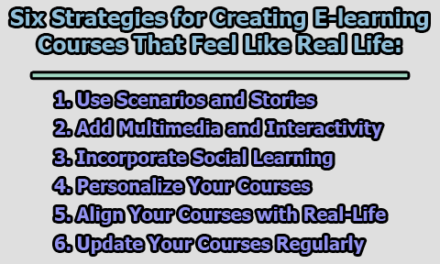

7 Smart, Fast Ways to Do Formative Assessment

Within these methods you’ll find close to 40 tools and tricks for finding out what your students know while they’re still learning.

Your content has been saved!

Formative assessment—discovering what students know while they’re still in the process of learning it—can be tricky. Designing just the right assessment can feel high stakes—for teachers, not students—because we’re using it to figure out what comes next. Are we ready to move on? Do our students need a different path into the concepts? Or, more likely, which students are ready to move on and which need a different path?

When it comes to figuring out what our students really know, we have to look at more than one kind of information. A single data point—no matter how well designed the quiz, presentation, or problem behind it—isn’t enough information to help us plan the next step in our instruction.

Add to that the fact that different learning tasks are best measured in different ways, and we can see why we need a variety of formative assessment tools we can deploy quickly, seamlessly, and in a low-stakes way—all while not creating an unmanageable workload. That’s why it’s important to keep it simple: Formative assessments generally just need to be checked, not graded, as the point is to get a basic read on the progress of individuals, or the class as a whole.

7 Approaches to Formative Assessment

1. Entry and exit slips: Those marginal minutes at the beginning and end of class can provide some great opportunities to find out what kids remember. Start the class off with a quick question about the previous day’s work while students are getting settled—you can ask differentiated questions written out on chart paper or projected on the board, for example.

Exit slips can take lots of forms beyond the old-school pencil and scrap paper. Whether you’re assessing at the bottom of Bloom’s taxonomy or the top, you can use tools like Padlet or Poll Everywhere , or measure progress toward attainment or retention of essential content or standards with tools like Google Classroom’s Question tool , Google Forms with Flubaroo , and Edulastic , all of which make seeing what students know a snap.

A quick way to see the big picture if you use paper exit tickets is to sort the papers into three piles : Students got the point; they sort of got it; and they didn’t get it. The size of the stacks is your clue about what to do next.

No matter the tool, the key to keeping students engaged in the process of just-walked-in or almost-out-the-door formative assessment is the questions. Ask students to write for one minute on the most meaningful thing they learned. You can try prompts like:

- What are three things you learned, two things you’re still curious about, and one thing you don’t understand?

- How would you have done things differently today, if you had the choice?

- What I found interesting about this work was...

- Right now I’m feeling...

- Today was hard because...

Or skip the words completely and have students draw or circle emojis to represent their assessment of their understanding.

2. Low-stakes quizzes and polls: If you want to find out whether your students really know as much as you think they know, polls and quizzes created with Socrative or Quizlet or in-class games and tools like Quizalize , Kahoot , FlipQuiz, Gimkit , Plickers , and Flippity can help you get a better sense of how much they really understand. (Grading quizzes but assigning low point values is a great way to make sure students really try: The quizzes matter, but an individual low score can’t kill a student’s grade.) Kids in many classes are always logged in to these tools, so formative assessments can be done very quickly. Teachers can see each kid’s response, and determine both individually and in aggregate how students are doing.

Because you can design the questions yourself, you determine the level of complexity. Ask questions at the bottom of Bloom’s taxonomy and you’ll get insight into what facts, vocabulary terms, or processes kids remember. Ask more complicated questions (“What advice do you think Katniss Everdeen would offer Scout Finch if the two of them were talking at the end of chapter 3?”), and you’ll get more sophisticated insights.

3. Dipsticks: So-called alternative formative assessments are meant to be as easy and quick as checking the oil in your car, so they’re sometimes referred to as dipsticks . These can be things like asking students to:

- write a letter explaining a key idea to a friend,

- draw a sketch to visually represent new knowledge, or

- do a think, pair, share exercise with a partner.

Your own observations of students at work in class can provide valuable data as well, but they can be tricky to keep track of. Taking quick notes on a tablet or smartphone, or using a copy of your roster, is one approach. A focused observation form is more formal and can help you narrow your note-taking focus as you watch students work.

4. Interview assessments: If you want to dig a little deeper into students’ understanding of content, try discussion-based assessment methods. Casual chats with students in the classroom can help them feel at ease even as you get a sense of what they know, and you may find that five-minute interview assessments work really well. Five minutes per student would take quite a bit of time, but you don’t have to talk to every student about every project or lesson.

You can also shift some of this work to students using a peer-feedback process called TAG feedback (Tell your peer something they did well, Ask a thoughtful question, Give a positive suggestion). When you have students share the feedback they have for a peer, you gain insight into both students’ learning.

For more introverted students—or for more private assessments—use Flipgrid , Explain Everything , or Seesaw to have students record their answers to prompts and demonstrate what they can do.

5. Methods that incorporate art: Consider using visual art or photography or videography as an assessment tool. Whether students draw, create a collage, or sculpt, you may find that the assessment helps them synthesize their learning . Or think beyond the visual and have kids act out their understanding of the content. They can create a dance to model cell mitosis or act out stories like Ernest Hemingway’s “Hills Like White Elephants” to explore the subtext.

6. Misconceptions and errors: Sometimes it’s helpful to see if students understand why something is incorrect or why a concept is hard. Ask students to explain the “ muddiest point ” in the lesson—the place where things got confusing or particularly difficult or where they still lack clarity. Or do a misconception check : Present students with a common misunderstanding and ask them to apply previous knowledge to correct the mistake, or ask them to decide if a statement contains any mistakes at all, and then discuss their answers.

7. Self-assessment: Don’t forget to consult the experts—the kids. Often you can give your rubric to your students and have them spot their strengths and weaknesses.

You can use sticky notes to get a quick insight into what areas your kids think they need to work on. Ask them to pick their own trouble spot from three or four areas where you think the class as a whole needs work, and write those areas in separate columns on a whiteboard. Have you students answer on a sticky note and then put the note in the correct column—you can see the results at a glance.

Several self-assessments let the teacher see what every kid thinks very quickly. For example, you can use colored stacking cups that allow kids to flag that they’re all set (green cup), working through some confusion (yellow), or really confused and in need of help (red).

Similar strategies involve using participation cards for discussions (each student has three cards—“I agree,” “I disagree,” and “I don’t know how to respond”) and thumbs-up responses (instead of raising a hand, students hold a fist at their belly and put their thumb up when they’re ready to contribute). Students can instead use six hand gestures to silently signal that they agree, disagree, have something to add, and more. All of these strategies give teachers an unobtrusive way to see what students are thinking.

No matter which tools you select, make time to do your own reflection to ensure that you’re only assessing the content and not getting lost in the assessment fog . If a tool is too complicated, is not reliable or accessible, or takes up a disproportionate amount of time, it’s OK to put it aside and try something different.

Ask Edutopia AI BETA

Special Education and Inclusive Learning

Mastering Formative and Summative Assessments in the Classroom

Understanding and utilising different types of assessments in education.

As educators, we use various forms of assessment to evaluate student learning, inform our instruction, and provide feedback. Four key types of assessment are formal, informal, summative, and formative. Understanding the distinctions and appropriate uses of each is crucial for effective teaching and learning. According to a 2019 National Center for Education Statistics study, schools that regularly use formative assessments saw a 10-15% improvement in overall student performance on standardized tests.

Formal vs. Informal Assessments

Formal assessments are structured, standardized evaluations that measure specific learning outcomes. These typically include tests, quizzes, projects, presentations, and other planned assessments that all students complete in the same manner. Formal assessments provide concrete data on student performance and progress.

Informal assessments, on the other hand, are more fluid and occur naturally throughout the learning process. These can include observing students during activities, listening to their discussions, reviewing their classwork, asking questions, and gauging their participation. Informal assessments give teachers valuable insights into student understanding and engagement on an ongoing basis.

While formal assessments are often graded, informal assessments usually are not. However, this is not a hard and fast rule – some informal assessments may be graded and some formal ones may not be. The key distinction is the level of structure and standardization.

Formative vs. Summative Assessments

Formative assessments are used to monitor student learning and provide ongoing feedback during the instructional process. Their primary purpose is to identify areas where students are struggling so teachers can adjust their teaching and provide targeted support. Examples include quick quizzes, exit tickets, draft essays, and practice problems.

- Pop quizzes

- Peer evaluations

- One-minute papers

Summative assessments evaluate student learning at the end of an instructional unit against a standard or benchmark. They are used to determine grades, measure progress, and assess cumulative knowledge. Examples include final exams, term papers, capstone projects, and standardized tests.

- Final exams

- Research papers

- Capstone projects

Contrary to some misconceptions, formative assessments can be graded, though they often are not. Summative assessments are typically graded, but this is not always the case. The key difference is when and how they are used in the learning process.

Nuances and Overlap

While these categories are useful, there is often overlap between them. For example:

- A unit test could be both summative (assessing mastery of that unit) and formative (informing instruction for the next unit).

- A graded homework assignment may be formal in structure but formative in purpose.

- An end-of-year standardized test is summative for that year but may be used formatively to plan for the next year.

- Informal observations can provide formative feedback to both students and teachers.

Assessment Type Comparison Chart:

Cultural Considerations: When designing assessments, be mindful of cultural biases. Ensure that questions and examples are inclusive and relevant to all students’ backgrounds.

Assessment Validity and Reliability:

- Validity: Ensure your assessment measures what it’s intended to measure.

- Reliability: Strive for consistency in results across different times or scorers.

Ethical Considerations:

- Maintain student privacy when sharing assessment results.

- Be aware of potential biases in assessment design and scoring.

- Ensure equal access to assessment preparation materials.

Differentiation Strategies:

- Offer multiple formats (e.g., written, oral, visual) for assessments.

- Allow extended time for students who need it.

- Provide scaffolding or simplified language where appropriate.

Assessment Issues Troubleshooting Guide:

Best practices for using assessments.

- Use a variety of assessment types to get a well-rounded picture of student learning.

- Align assessments closely with learning objectives and instructional methods.

- Use formative assessments frequently to monitor progress and adjust teaching.

- Provide clear expectations and criteria for formal and summative assessments.

- Use assessment data to inform instruction and provide targeted support.

- Involve students in the assessment process through self-evaluation and peer feedback.

- Balance the use of graded and ungraded assessments to motivate without overstressing students.

- Consider the purpose of each assessment when deciding whether to grade it.

- Use summative assessments as opportunities for students to demonstrate mastery in authentic ways.

- Reflect on assessment results to improve both teaching and assessment practices.

Effective use of various assessment types is crucial for supporting student learning and improving instruction. By understanding the nuances of formal, informal, formative, and summative assessments, teachers can create a comprehensive assessment strategy that provides valuable insights and promotes student success. Remember, the ultimate goal of any assessment should be to enhance the learning process and outcomes for all students.

Actionable Steps:

Audit your current assessment practices. Incorporate at least one new assessment type into your next unit. Collect student feedback on assessment methods. Collaborate with colleagues to share effective assessment strategies. Regularly review and adjust your assessment approach based on student outcomes.

Please share if you enjoyed this post.

Discover more from special education and inclusive learning.

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Classification

- Physical Education

- Travel and Tourism

- BIBLIOMETRICS

- Banking System

- Real Estate

Select Page

The Use of Formative and Summative Assessments in the Classroom

Posted by Md. Harun Ar Rashid | Aug 30, 2023 | Teaching & Learning

The Use of Formative and Summative Assessments in the Classroom:

In the realm of education, assessments play a pivotal role in shaping the learning journey of students, providing valuable insights into their progress and understanding. Formative and summative assessments stand as two cornerstone pillars in this process, each serving distinct yet interconnected purposes. Formative assessments involve ongoing, real-time evaluations that facilitate immediate feedback and guide instructional strategies (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Hattie & Timperley, 2007). On the other hand, summative assessments encapsulate the cumulative learning outcomes at specific points in time, often determining the degree of mastery attained by students (Gullickson & Ellwein, 1985; Nitko, 2001). This article embarks on the use of formative and summative assessments in the classroom.

1. Formative Assessment: Nurturing Continuous Learning Through Timely Feedback:

1.1 Definition and Purpose: Formative assessment, often referred to as “assessment for learning,” is a pedagogical approach that involves the ongoing assessment of student understanding and progress throughout the learning process (Black & Wiliam, 1998). Unlike traditional evaluations that occur at the end of a unit or course, formative assessments are integrated into the instructional cycle, providing both educators and learners with immediate feedback to guide further learning (Sadler, 1989). The primary purpose of formative assessment is to inform instruction, enabling educators to adapt their teaching methods based on students’ evolving needs, strengths, and challenges (Heritage, 2007).

1.2 Characteristics of Effective Formative Assessments: Effective formative assessments possess several key characteristics that contribute to their ability to enhance learning outcomes (Hattie & Timperley, 2007):

- Immediacy: Formative assessments are conducted in real-time, allowing educators to identify misconceptions and gaps in understanding while the learning is still ongoing.

- Actionable Feedback: Feedback provided in formative assessments is specific, constructive, and actionable, guiding students toward areas that need improvement and strategies for enhancement.

- Student Involvement: Formative assessments often engage students actively in the assessment process, encouraging them to self-assess, reflect, and set learning goals.

- Varied Formats: They encompass a range of formats, including quizzes, polls, discussions, assignments, and observations, catering to diverse learning styles and objectives.

- Informing Instruction: The insights gained from formative assessments are immediately used to adjust instructional strategies, reteach concepts, or introduce additional resources.

1.3 Benefits of Formative Assessments: Formative assessments offer numerous benefits to both educators and students:

- Personalized Learning: They allow educators to tailor their teaching to the individual needs and strengths of each student.

- Motivation: Regular feedback fosters a sense of achievement and progress, motivating students to remain engaged and active in their learning journey.

- Reduced Achievement Gaps: By identifying and addressing learning gaps early on, formative assessments help in minimizing achievement disparities among students.

- Higher-Level Thinking: They encourage critical thinking and metacognition as students analyze their own learning process.

- Improved Teaching Strategies: Educators can refine their instructional methods based on real-time insights, leading to more effective teaching.

- Continuous Improvement: Both educators and students experience ongoing growth as formative assessments drive continuous learning and refinement.

1.4 Challenges and Misconceptions: Despite their evident benefits, formative assessments also come with challenges that need careful consideration:

- Time Management: Integrating frequent formative assessments requires strategic planning to ensure they complement the curriculum without overwhelming students.

- Grading Burden: Providing timely feedback can be time-consuming, posing a challenge for educators, particularly in larger classes.

- Validity and Reliability: Ensuring the validity and reliability of formative assessments can be challenging due to their informal nature.

- Misalignment: If not well-aligned with learning objectives, formative assessments might miss the mark in effectively guiding learning.

2. Strategies for Implementing Formative Assessment:

Formative assessment strategies are a cornerstone of effective teaching practices, enabling educators to gauge student progress, adjust instruction, and provide timely feedback. These strategies create a dynamic and responsive learning environment that fosters growth and continuous improvement. Here, we delve into various practical strategies for implementing formative assessments in the classroom:

2.1 Classroom Discussions and Questioning Techniques: Engaging students in discussions and using effective questioning techniques are powerful ways to formatively assess their understanding. Teachers can pose open-ended questions that encourage critical thinking and class participation. Incorporating techniques like Think-Pair-Share or Socratic seminars promotes peer interaction, idea exchange, and reflective learning (Birenbaum & Dochy, 1996; Mercer & Littleton, 2007).

2.2 Quizzes and Polls: Frequent low-stakes quizzes and polls provide valuable insights into student comprehension and retention. These can be administered in various formats, such as multiple-choice questions, short answer questions, or even interactive online platforms. Instant feedback on quiz results enables students to identify areas that require further review (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006; Davenport & Davenport, 1985).

2.3 Peer and Self-Assessment: Peer and self-assessment foster metacognitive skills and encourage students to take ownership of their learning. Through guided rubrics, students can evaluate their own work or that of their peers, identifying strengths and areas for improvement. This process not only enhances their understanding but also nurtures collaboration and communication skills (Andrade & Du, 2005; Falchikov & Goldfinch, 2000).

2.4 Feedback and Feedforward Mechanisms: Timely and constructive feedback is a hallmark of formative assessment. Teachers can provide written or verbal feedback that focuses on specific learning objectives and offers guidance on improvement. Additionally, incorporating feedforward, which suggests strategies for future growth, empowers students to actively enhance their performance (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Sadler, 1989).

2.5 Learning Journals and Reflective Activities: Integrating learning journals or reflective activities into the curriculum encourages students to synthesize their learning experiences. These personal accounts provide insight into individual progress, challenges, and emerging insights. Through these reflections, teachers can identify common misconceptions and adjust instructional approaches accordingly (Moon, 2001; Schön, 1987).

3. Summative Assessment:

Summative assessment serves as a culminating evaluation that gauges students’ overall mastery of learning objectives and curriculum content at specific points in time. Unlike formative assessment, which focuses on ongoing feedback and instructional adjustments, summative assessment provides a snapshot of students’ achievements and informs decisions about their progression and attainment. Below, we explore the key aspects of summative assessment, its purpose, design, benefits, and challenges:

3.1 Purpose and Characteristics: Summative assessments are typically conducted at the end of a learning period, module, or course to measure the extent to which students have met established educational standards and objectives. They offer a comprehensive overview of students’ knowledge, skills, and competencies, allowing educators and institutions to make informed decisions about students’ progress and readiness for further learning opportunities.

3.2 Differentiating from Formative Assessment: While both formative and summative assessments are essential components of effective instruction, they serve distinct purposes. Formative assessments focus on guiding instruction, offering ongoing feedback, and fostering learning adjustments, while summative assessments emphasize evaluating students’ overall achievement and determining whether learning goals have been met.

3.3 Benefits of Summative Assessments:

- Measuring Mastery: Summative assessments provide a clear measure of students’ mastery of the material covered throughout the learning period.

- Accountability: They offer a basis for evaluating teaching effectiveness, curriculum alignment, and institutional accountability.

- Feedback for Improvement: Summative assessment results can be used to refine future instructional strategies and curriculum design.

- Credentialing: Summative assessments often play a role in certifying students’ readiness for advancement, such as moving from one grade level to another or earning a degree.

3.4 Effective Summative Assessment Design:

- Clear Learning Objectives: Clearly defined and aligned learning objectives are essential for designing meaningful summative assessments.

- Assessment Methods: Choose appropriate assessment methods such as exams, research projects, presentations, or performance evaluations.

- Rubrics: Develop detailed rubrics to guide consistent and transparent evaluation, helping both students and assessors understand performance expectations.

- Reliability and Validity: Ensure that assessments are reliable (yield consistent results) and valid (measure what they are intended to measure).

3.5 Limitations and Challenges:

- Pressure and Stress: Summative assessments can induce anxiety and stress in students, potentially impacting their performance.

- Limited Context: They might not fully capture the nuances of a student’s learning journey, as they focus on specific outcomes at a given point.

- Inadequate Feedback: Summative assessments often provide limited feedback for improvement, as they are outcome-oriented.

3.6 Addressing Challenges:

- Balanced Approach: Combine formative and summative assessment strategies to provide a more holistic view of student learning.

- Feedback Integration: Offer constructive feedback along with summative assessment results to guide students’ growth.

- Diverse Assessment Methods: Incorporate a mix of assessment methods to accommodate different learning styles and abilities.

3.7 Ethical Considerations:

- Fairness and Equity: Ensure assessments are fair, unbiased, and accommodate diverse learners.

- Avoiding High-Stakes: Mitigate the negative impact of high-stakes summative assessments by incorporating varied assessment methods.

4. Effective Summative Assessment Design:

Designing effective summative assessments is a critical aspect of the educational process. These assessments provide a comprehensive overview of students’ learning outcomes and help educators make informed decisions about their progress. To ensure the validity, reliability, and fairness of summative assessments, careful planning and thoughtful design are essential. Here are the key considerations for creating impactful summative assessments:

4.1 Clear Learning Objectives: Begin by establishing clear and specific learning objectives that align with the curriculum. These objectives serve as the foundation for designing assessment tasks that accurately measure what students are expected to have learned. Clear objectives also guide students’ focus and help them understand the purpose of the assessment.

4.2 Assessment Methods Selection: Choose assessment methods that align with the learning objectives and allow students to demonstrate their understanding effectively. Common summative assessment methods include:

- Written Exams: Traditional tests with a mix of multiple-choice, short answer, and essay questions.

- Projects: Assignments that require students to apply knowledge and skills to real-world scenarios.

- Presentations: Students showcase their understanding through oral communication and visual aids.

- Performance Assessments: Practical demonstrations of skills or processes.

4.3 Development of Rubrics: Create detailed and transparent rubrics that outline the criteria and performance expectations for each assessment task. Rubrics not only guide the grading process but also provide students with a clear understanding of what is expected, enhancing their performance and reducing subjectivity in evaluation.

4.4 Reliability and Validity: Ensure the assessments are reliable and valid. Reliability refers to the consistency of results, meaning that if the assessment were administered multiple times, it would yield similar outcomes. Validity ensures that the assessment measures what it is intended to measure. Both reliability and validity enhance the credibility of assessment results.

4.5 Authenticity and Real-World Relevance: Craft assessment tasks that mirror real-world scenarios, encouraging students to apply their knowledge and skills in meaningful ways. Authentic assessments not only engage students but also better prepare them for practical challenges they may encounter beyond the classroom.

4.6 Alignment with Bloom’s Taxonomy: Design assessments that address various cognitive levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. This ensures a balanced assessment that assesses not only basic knowledge but also higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis, and evaluation.

4.7 Timing and Scheduling: Consider the appropriate timing for administering summative assessments. Avoid scheduling multiple high-stakes assessments close together, as this can overwhelm students and affect their performance. Also, allow sufficient time for students to prepare and review the material.

4.8 Accommodations and Accessibility: Ensure that the assessment design accommodates diverse learners, including those with special needs or different learning styles. Provide necessary accommodations to create an equitable testing environment for all students.

4.9 Pilot Testing: Before administering summative assessments, conduct pilot tests to identify potential issues with questions, instructions, or timing. Pilot testing helps refine the assessment design and ensures that the assessment accurately measures what it intends to.

4.10 Feedback and Continuous Improvement: After the assessment, provide meaningful feedback to students that highlights their strengths and areas for improvement. Additionally, gather feedback from students about the assessment experience to continually improve the assessment design and administration.

5. Balancing Formative and Summative Assessment Strategies:

Achieving a harmonious integration of formative and summative assessment strategies is essential for promoting holistic student learning and growth. While formative assessments provide ongoing feedback and support instructional adjustments, summative assessments offer a final evaluation of student achievement. Here, we delve into the significance of striking a balance between these two assessment types and explore strategies for effective implementation:

5.1 Complementary Roles for Enhanced Learning: Viewed as dynamic counterparts rather than isolated entities, formative and summative assessments converge to enhance learning outcomes. Formative assessments, such as classroom discussions, quizzes, and peer evaluations, facilitate real-time feedback and encourage student engagement. They allow educators to gauge individual and collective understanding, enabling timely interventions and instructional adjustments. In contrast, summative assessments, such as end-of-unit exams or final projects, provide a comprehensive evaluation of the learning journey. They offer insights into the depth of knowledge attained, enabling educators to make informed decisions about student progression and achievement (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

5.2 Integration into the Educational Fabric: To strike the right balance, integrate formative assessments seamlessly into instructional practices. Use questioning techniques that stimulate critical thinking and encourage active participation. Leverage technology to administer online quizzes and polls that provide instant feedback, allowing students to gauge their progress. Engage in classroom discussions that serve as formative assessments in real time, offering insight into comprehension levels and promoting dialogue among peers. These strategies not only facilitate learning but also inform adjustments that prepare students for summative evaluations (Heritage, 2007; Mercer & Littleton, 2007).

5.3 Transitioning from Learning to Evaluation: While formative assessments guide learning, summative assessments encapsulate its culmination. Constructing effective summative assessments requires meticulous planning. Begin by defining clear learning objectives aligned with curriculum standards. Select assessment methods, ranging from written exams to practical projects, that accurately measure students’ grasp of the subject matter. Develop comprehensive rubrics that outline performance criteria, ensuring transparent and consistent evaluation. By aligning assessments with higher-order thinking skills, such as analysis and synthesis, educators encourage deeper understanding and application of knowledge (Bloom et al., 1956; Brookhart, 2013).

5.4 Feedback as a Bridge: Formative assessments bridge the gap between learning and evaluation by providing students with constructive feedback. This feedback loop informs students of their strengths and areas for improvement, equipping them to refine their understanding and approach. By infusing summative assessments with this formative element, educators acknowledge the iterative nature of learning and empower students to approach final evaluations as opportunities for growth. Integrating formative feedback into summative evaluations enhances student self-awareness, which, in turn, cultivates a sense of ownership over their learning (Popham, 2008; Sadler, 1989).

5.5 Cultivating Lifelong Learning: The harmony between formative and summative assessments fosters a culture of lifelong learning. Students understand that their learning journey encompasses not only knowledge acquisition but also continuous improvement. By experiencing the interplay of formative and summative assessments, students develop metacognitive skills, adaptability, and resilience—attributes that serve them beyond the classroom. Educators are instrumental in fostering this mindset by illustrating how both assessment types contribute to personal and intellectual growth (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

5.6 Tailoring for Diverse Learners: Effective balance requires recognizing and accommodating diverse learners’ needs. Inclusive assessment practices ensure that both formative and summative assessments consider variations in learning styles, abilities, and backgrounds. Providing flexible assessment methods, offering reasonable accommodations, and valuing multiple forms of expression contribute to equitable evaluation and meaningful learning experiences for all students.

5.7 Constant Evolution: The art of balancing formative and summative assessments involves constant refinement. Educators should continually reflect on their assessment strategies, seek feedback from students, and collaborate with peers to share best practices. This iterative process enriches assessment literacy, enhances instructional practices, and aligns assessment strategies with evolving educational goals.

6. Technology and Assessment: Enhancing Educational Evaluation in the Digital Age

In the contemporary landscape of education, technology has revolutionized various aspects of teaching and learning. One area that has witnessed significant transformation is assessment. Technological advancements have introduced innovative tools and methodologies that enrich the assessment process, offering educators new opportunities to gather data, provide feedback, and enhance student learning outcomes. Here, we delve into the intricate relationship between technology and assessment, exploring its benefits, challenges, and ethical considerations:

6.1 Digital Tools for Varied Assessment Formats: Technology offers a wide array of tools to diversify assessment formats. Online platforms enable educators to create quizzes, surveys, and interactive assignments that engage students and provide instant feedback. These tools accommodate different learning styles and allow for adaptive assessment, where questions adjust based on students’ responses, providing a tailored evaluation experience (Deng & Yuen, 2011; Clariana & Wallace, 2002).

6.2 Automated Grading and Feedback: One of the notable advantages of technology is the automation of grading and feedback processes. Online assessment platforms can automatically score multiple-choice questions and even analyze written responses using natural language processing. This efficiency frees up educators’ time, allowing them to focus on more nuanced aspects of teaching, such as providing detailed feedback and guiding students toward improvement (Tao & Gunter, 2016).

6.3 E-Portfolios and Multimedia Presentations: Technology enables the creation of electronic portfolios (e-portfolios), which showcase students’ growth over time through a collection of artifacts, reflections, and self-assessments. E-portfolios provide a holistic view of students’ skills and competencies, demonstrating their progress in various dimensions of learning. Similarly, multimedia presentations allow students to showcase their understanding in dynamic ways, incorporating visuals, audio, and interactive elements (Cambridge, 2001).

6.4 Peer Collaboration and Review: Digital tools facilitate peer collaboration and review, fostering active learning and enhancing assessment practices. Online platforms enable students to collaboratively work on projects, offering insights into each other’s perspectives and learning styles. Peer review mechanisms allow students to assess and provide feedback on their peers’ work, promoting critical thinking, communication skills, and a deeper understanding of subject matter (Falchikov, 2005; Dreon et al., 2010).

6.5 Challenges and Ethical Considerations: While technology enriches assessment practices, it also presents challenges that must be navigated thoughtfully. Concerns related to digital equity and access need to be addressed to ensure that all students have equal opportunities for success. Moreover, educators should be cautious about overreliance on automated grading, as complex skills and higher-order thinking may not be accurately evaluated by algorithms alone. Ethical considerations include safeguarding student data privacy and maintaining academic integrity in online assessments (Carey, 2016; Hodges et al., 2017).

6.6 Personalized Learning and Analytics: Technology enables the collection of vast amounts of data on student performance, which can be harnessed for personalized learning experiences. Learning analytics provide insights into students’ progress, preferences, and challenges, enabling educators to tailor instruction to individual needs. Adaptive learning platforms use data to deliver content and assessments that align with each student’s proficiency level, optimizing learning outcomes (Siemens & Long, 2011; Lonn & Teasley, 2009).

6.7 Hybrid Assessment Environments: The synergy between technology and assessment has given rise to hybrid assessment environments that blend traditional methods with digital tools. Educators can design assessments that incorporate both online quizzes and in-class presentations, allowing students to demonstrate their understanding through diverse mediums. This approach caters to different learning preferences and integrates technology seamlessly into the learning experience.

7. Feedback and Student Engagement: Nurturing Learning through Constructive Guidance

Feedback serves as a cornerstone of effective education, fostering student engagement, growth, and achievement. When strategically incorporated into the learning process, feedback not only provides students with valuable insights into their progress but also cultivates a sense of ownership over their learning journey. This symbiotic relationship between feedback and student engagement forms a powerful duo that propels learning to new heights. Here, we delve into the intricate dynamics of how feedback enhances student engagement and strategies for optimizing this relationship:

7.1 The Essence of Constructive Feedback: Feedback encompasses more than just providing answers or grades—it’s a nuanced process that offers guidance and insights into students’ performance. Constructive feedback highlights strengths while pinpointing areas for improvement, encouraging a growth mindset. Timely and specific feedback is particularly effective in guiding students toward mastery by focusing on learning objectives (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Sadler, 1989).

7.2 Feedback as a Catalyst for Engagement: Effective feedback sparks engagement by fostering a dynamic interaction between students and their learning. When students receive feedback that is personalized, relevant, and actionable, they are more likely to invest in the learning process. Feedback fuels curiosity and encourages exploration, as students strive to understand concepts deeply and achieve better outcomes (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Black & Wiliam, 1998).

7.3 Timely Nature and Formative Impact: Timely feedback is a potent catalyst for student engagement. When students receive feedback during their learning journey—rather than solely after summative assessments—they can make adjustments in real-time. Formative feedback that occurs while students are actively working on tasks enhances their sense of agency and commitment to the learning process (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Shute, 2008).

7.4 Peer and Self-Assessment: Engaging students in peer and self-assessment cultivates metacognitive skills and ownership over their learning. Peer assessment promotes active involvement and encourages students to critically evaluate their peers’ work, fostering a deeper understanding of the subject matter. Self-assessment empowers students to reflect on their progress, set goals, and take responsibility for their learning journey (Falchikov & Goldfinch, 2000; Andrade & Du, 2005).

7.5 Feedback Diversity: Employ a diverse range of feedback methods to engage students effectively. Written comments, verbal discussions, audio recordings, and visual annotations offer various avenues for delivering feedback that resonates with individual learning preferences. Personalizing the feedback process enhances its impact on students’ motivation and learning outcomes (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Carless & Boud, 2018).

7.6 Clear Communication and Dialogue: Effective feedback hinges on clear communication. Frame feedback in a constructive and supportive manner, focusing on specific actions rather than the individual. Encourage an ongoing dialogue where students can seek clarification, ask questions, and collaborate to improve their understanding. Such interactions foster a sense of partnership and a shared commitment to learning (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Carless, 2006).

7.7 Incorporating Feedforward: Taking feedback a step further, incorporate feedforward—guidance on how to enhance future performance. By suggesting actionable steps for improvement, feedforward transforms feedback into a roadmap for growth. Students not only grasp where they can improve but also gain insights into how to achieve those improvements (Sadler, 1989; Carless, 2015).

7.8 Feedback Literacy: Educate students on how to effectively interpret and utilize feedback. Cultivate feedback literacy by teaching students how to analyze comments, extract meaningful insights, and implement suggested improvements. Empowering students with these skills fosters a proactive approach to learning and fuels intrinsic motivation (Price et al., 2011; Winstone & Carless, 2019).

8. Adapting Assessments for Diverse Learners: Fostering Inclusivity and Equity

In today’s diverse educational landscape, adapting assessments to accommodate the varied needs, strengths, and learning styles of students is crucial. As educators strive to create inclusive and equitable learning environments, tailoring assessments becomes a cornerstone of fostering meaningful engagement and ensuring that all learners can showcase their true potential. Here, we explore the multifaceted process of adapting assessments for diverse learners, examining strategies, considerations, and benefits:

8.1 Understanding Diverse Learners: Begin by recognizing that diversity encompasses a range of factors, including cultural backgrounds, learning abilities, linguistic skills, and individual preferences. Cultivating a deep understanding of your students’ profiles enables you to make informed decisions about how to adapt assessments effectively (Gay, 2010; Tomlinson, 2014).

8.2 Universal Design for Learning (UDL): UDL principles advocate for designing assessments that cater to diverse learners from the outset. UDL encourages multiple means of representation, engagement, and expression, accommodating varied learning preferences. By incorporating flexibility, multimedia, and varied modes of assessment, educators create assessments that resonate with a wider spectrum of students (CAST, 2018; Meyer et al., 2014).

8.3 Varied Assessment Formats: Offer diverse assessment formats that provide options for students to demonstrate their understanding. While some students might excel in written exams, others may thrive through oral presentations, visual projects, or practical demonstrations. Diversifying assessment formats taps into students’ strengths and allows them to showcase their mastery in ways that align with their abilities (McTighe & O’Connor, 2005; Rodgriguez & Baud, 2011).

8.4 Flexible Timelines: Recognize that diverse learners may require different amounts of time to complete assessments. Providing flexible timelines or extended time for certain students can alleviate stress and ensure that they have an equitable opportunity to demonstrate their learning without the pressure of time constraints (Burgstahler, 2015; Stowell & Bennett, 2010).

8.5 Alternative Assessment Modalities: Leverage technology to create alternative assessment modalities that cater to specific needs. Screen readers, voice recognition software, and captioning tools enhance accessibility for students with visual or auditory impairments. These adaptations empower students to engage with assessments independently (Burgstahler & Cory, 2008; Higgins & Boone, 2019).

8.6 Clear Assessment Instructions: Craft assessment instructions that are clear, concise, and accessible to all students. Avoid ambiguous language or jargon that might confuse learners. Providing step-by-step guidance ensures that students understand the task requirements and can focus on demonstrating their knowledge (Herrington & Herrington, 2006; Fluckiger et al., 2010).

8.7 Collaborative Assessments: Promote collaboration by designing assessments that involve group work or peer evaluations. Collaborative assessments not only accommodate social learners but also foster an inclusive environment where students can benefit from diverse perspectives and experiences (Boud & Lee, 2005; Light et al., 2009).

8.8 Personalized Accommodations: Work closely with students to determine personalized accommodations based on their unique needs. Individualized education plans (IEPs) or accommodations documents provide valuable insights into the support required for each student. Establish a partnership with learners to ensure that the adaptations are aligned with their preferences and comfort (Rose & Meyer, 2002; Beed & Coutts, 2018).

8.9 Cultivating a Growth Mindset: Promote a growth mindset among students by emphasizing that adaptations are not indicative of limitations but rather tools that enable them to succeed. Normalize the process of seeking assistance, embracing adaptations, and advocating for one’s learning needs (Dweck, 2006; National Center on Universal Design for Learning, 2011).

8.10 Ongoing Reflection and Improvement: Reflect on the effectiveness of adapted assessments and gather feedback from diverse learners. Continuously refine your approach by incorporating insights from students’ experiences and adjusting adaptations accordingly. This iterative process demonstrates a commitment to inclusivity and constant enhancement (Archer et al., 2010; Harrell & Bower, 2015).

9. Assessment for Learning Progression: Guiding Students on the Path to Mastery

Assessment for learning progression is a dynamic process that empowers educators to monitor and guide students’ growth over time. It involves using assessments as tools to track individual progress, identify learning gaps, and adapt instructional strategies accordingly. This approach shifts the focus from mere evaluation to active guidance, fostering a culture of continuous improvement and providing students with the scaffolding they need to achieve mastery. Here, we delve into the intricate details of assessment for learning progression, exploring its principles, methodologies, and benefits:

9.1 Principles of Assessment for Learning Progression: At the core of assessment for learning progression lies the principle of personalized learning. Educators recognize that each student follows a unique trajectory of development and understanding. Assessment strategies are designed to illuminate the individual steps students take along their learning journeys, allowing educators to tailor support and interventions to meet their specific needs (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Sadler, 1989).

9.2 Tracking Learning Over Time: Assessment for learning progression involves consistently assessing students’ understanding at different points in time. This ongoing tracking provides a panoramic view of their growth, revealing patterns of achievement and areas that require additional attention. Regular assessments highlight not only the destination (final mastery) but also the trajectory of learning (progression) (Popham, 2008; Wiliam, 2011).

9.3 Diagnosing Learning Gaps: One of the primary goals of assessment for learning progression is to diagnose learning gaps. By analyzing assessment data, educators can identify specific concepts or skills that students struggle to grasp. This diagnostic approach allows for targeted interventions, enabling students to bridge these gaps and move forward in their learning (Black & Wiliam, 1998; Hattie, 2012).

9.4 Formative Feedback and Support: Feedback is a linchpin of assessment for learning progression. Timely, specific, and actionable feedback guides students toward improvement. Educators leverage formative assessment data to provide insights into strengths, areas for growth, and strategies for enhancement. This personalized guidance supports students as they progress toward mastery (Sadler, 1989; Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

9.5 Adjusting Instructional Strategies: The data gleaned from assessment for learning progression inform instructional decisions. Educators adapt teaching methods, pacing, and resources based on students’ progress. This responsive approach ensures that students receive the right level of challenge and support, maximizing their potential for achievement (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006; Heritage, 2007).

9.6 Individualized Learning Pathways: Assessment for learning progression paves the way for individualized learning pathways. It acknowledges that students advance at different rates and might require diverse strategies to achieve mastery. These pathways are not predefined but rather emerge as educators dynamically tailor instruction to meet students where they are (Tomlinson, 2014; Wiggins & McTighe, 2005).

9.7 Portfolio and Artifact-Based Assessment: Portfolios and artifact-based assessments are integral to tracking learning progression. Students curate their work over time, showcasing their development and growth. These collections provide a tangible record of progress, allowing both educators and students to reflect on the journey toward mastery (Cambridge, 2001; Darling-Hammond & Adamson, 2010).

9.8 Student Agency and Goal Setting: Assessment for learning progression empowers students to take ownership of their learning. By actively participating in the assessment process, setting goals, and monitoring their own progress, students become co-creators of their educational journeys. This agency enhances motivation and engagement (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Zimmerman, 2002).

9.9 Cultivating a Growth Mindset: The process of assessment for learning progression nurtures a growth mindset. Students understand that learning is a continuous journey and that setbacks are opportunities for improvement. Embracing challenges and persisting through difficulties become essential components of the learning experience (Dweck, 2006; Hattie & Timperley, 2007).

9.10 Celebrating Success and Reflecting on Growth: Assessment for learning progression involves celebrating successes and reflecting on growth. Recognizing achievements, no matter how incremental, reinforces the value of effort and the progress made. It also encourages metacognition—students begin to recognize their learning strategies and how they contribute to their progress (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Price et al., 2011).

10. Teacher Professional Development on Assessment: Nurturing Expertise for Effective Evaluation

Teacher professional development on assessment is a pivotal component of enhancing educational practices and student learning outcomes. As the landscape of education evolves, educators need to continually refine their assessment strategies to align with best practices, innovative methodologies, and the diverse needs of their students. Professional development in assessment equips teachers with the knowledge, skills, and tools they need to create meaningful, accurate, and equitable assessment experiences. Here, we delve into the comprehensive landscape of teacher professional development on assessment, exploring its importance, strategies, and impact:

10.1 The Importance of Assessment Professional Development: Assessment is an integral facet of education that demands continuous refinement and improvement. Teacher professional development in assessment acknowledges the dynamic nature of evaluation practices and equips educators with the capacity to navigate the complexities of designing, administering, and interpreting assessments. This development ensures that teachers remain adept at fostering deep learning, accurate evaluation, and informed instructional decisions (Pellegrino et al., 2001; Stiggins & Chappuis, 2005).

10.2 Key Areas of Assessment Professional Development:

- Assessment Literacy: Equip teachers with a comprehensive understanding of assessment principles, terminology, and methodologies. This literacy empowers educators to critically evaluate assessments, select appropriate formats, and interpret results accurately.

- Data Analysis: Train teachers in data analysis techniques that enable them to glean insights from assessment results. Teachers learn how to identify learning trends, diagnose student needs, and tailor instruction accordingly.

- Designing Effective Assessments: Educate teachers in the art of crafting assessments that align with learning objectives, measure desired outcomes, and promote critical thinking and problem-solving.

- Providing Constructive Feedback: Train educators to deliver feedback that guides student growth and learning. Effective feedback focuses on strengths, offers actionable insights, and fosters a growth mindset.

- Equity and Inclusion: Highlight the importance of equitable assessment practices that accommodate diverse learners. Educators learn to minimize biases and provide fair assessment opportunities for all students (Popham, 2006; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

10.3 Delivery Strategies for Assessment Professional Development:

- Workshops and Seminars: Offer interactive workshops that combine theory, hands-on practice, and collaborative discussions. These sessions allow educators to explore new assessment methodologies and strategies.

- Online Modules: Provide self-paced online modules that educators can access anytime, anywhere. These modules can delve into specific assessment topics and cater to different learning preferences.

- Peer Learning Communities: Foster communities of practice where educators share insights, challenges, and success stories related to assessment. Collaborative learning enhances collective expertise.

- Coaching and Mentoring: Pair experienced educators with novices for personalized guidance on assessment practices. Coaching relationships facilitate one-on-one support and skill development.

- Incorporate Real-World Examples: Embed real-world assessment examples and case studies into professional development activities. This contextualizes learning and demonstrates practical application (Guskey, 2000; Guskey & Sparks, 2001).

10.4 Impact of Assessment Professional Development:

- Enhanced Instructional Decision-Making: Teachers equipped with robust assessment skills make informed decisions on instructional strategies, adapting their approaches to meet student needs.

- Improved Student Learning Outcomes: Effective assessments aligned with learning goals contribute to improved student performance and mastery of subject matter.

- Reduced Achievement Gaps: Equitable assessment practices diminish achievement gaps by providing all students with fair opportunities to demonstrate their knowledge and skills.

- Cultivation of Reflective Practitioners: Assessment professional development nurtures a culture of reflection, as educators continually evaluate their practices and strive for improvement.

- Teacher Satisfaction and Retention: Empowered teachers who feel confident in their assessment practices experience greater job satisfaction and are more likely to remain in the profession (Yoon et al., 2007; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

10.5 Sustaining Professional Development: To ensure the longevity and efficacy of assessment professional development, establish a culture of continuous improvement. Encourage ongoing learning through peer collaboration, encourage educators to share insights and challenges, and provide access to updated resources and research (Guskey & Yoon, 2009; Darling-Hammond et al., 2017).

At the end of the day, we can say that in school, there are two types of tests that help us learn better. The first type is called “formative” tests. These tests happen while we’re learning new things. They’re like small clues that show us if we’re understanding the lessons or if we need to try harder. Formative tests help us improve as we go along. The second type is called “summative” tests. These are the big tests we take at the end of a topic or school term. They show how well we’ve learned everything. Both types of tests are important because they help teachers teach us better and help us show what we’ve learned. When teachers use both types of tests together, it makes learning more interesting and helps us become better students.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is the difference between formative and summative assessments?

Formative assessments happen during learning to help students understand and improve. They’re like checkpoints that show where you’re doing well and where you need more practice. Summative assessments are bigger tests that happen at the end of a lesson or a period. They measure how much you’ve learned overall.

How do formative assessments help students learn better?

Formative assessments give students feedback while they’re learning. This helps them see their progress and figure out what they need to work on. It’s like getting tips to do better as you go along.

Why are summative assessments important?

Summative assessments show how well you’ve learned everything by the end of a lesson or period. They give a final picture of what you know and what you still need to practice. Teachers use these tests to see if their teaching methods are working and to give grades.

How can teachers use formative assessments in the classroom?

Teachers can use short quizzes, discussions, or even asking questions during class as formative assessments. These help them understand how well students are grasping the material, so they can adjust their teaching to help students improve.

What are some examples of summative assessments?

Summative assessments include final exams, end-of-term projects, and standardized tests. These tests give a clear picture of how much students have learned over a longer period.

Can formative and summative assessments be used together?

Absolutely! Using both types of assessments together is very helpful. Formative assessments show how students are doing while they learn, and summative assessments give a final overview. This helps teachers and students work together to achieve better results.

How do assessments help teachers improve their teaching methods?

Assessments give teachers insights into what’s working and what needs improvement. If many students are struggling with a certain topic, teachers can adjust their teaching methods to help everyone understand better.

Do assessments only measure academic subjects?

No, assessments can measure various skills and knowledge. They can include things like presentations, creative projects, or even practical skills. Assessments help measure what students have learned in different areas.

How do assessments benefit students?

Assessments help students see their progress, identify areas for improvement, and build confidence. They also prepare students for real-world situations where they need to show what they’ve learned.

What’s the role of technology in assessments?

Technology can make assessments more engaging and efficient. Online quizzes, interactive activities, and digital tools can provide immediate feedback and help students learn in a more interactive way.

How can teachers make sure assessments are fair for all students?

Teachers should consider students’ diverse needs and learning styles when creating assessments. Providing options, giving clear instructions, and being open to questions help ensure that assessments are fair and accessible to everyone.

Can assessments encourage students to keep learning?

Yes, assessments can motivate students to keep improving. When students see their progress and understand where they need to focus, it encourages them to work harder and keep learning.

Are assessments only for grading purposes?

Assessments are more than just grades. They’re tools for learning and growth. Grades are one part of assessments, but the main goal is to help students learn better and become more skilled.

How can teachers balance both types of assessments in the classroom?

Balancing formative and summative assessments involves using formative assessments to guide teaching and provide ongoing feedback, and then using summative assessments to measure overall learning. This balance helps create a complete learning experience.

Can assessments help students become better learners?

Yes, assessments help students understand their strengths and weaknesses. This self-awareness makes them better at setting goals, improving their study habits, and becoming more effective learners.

How can students benefit from both formative and summative assessments?

Formative assessments help students understand their progress and make improvements while learning. Summative assessments show how much they’ve learned over time. Together, they help students succeed in their studies and beyond.

What’s the role of feedback in assessments?

Feedback is a crucial part of assessments. It helps students understand what they did well and where they need to improve. Constructive feedback guides their learning journey.

How can assessments contribute to a positive learning environment?

Assessments help create a supportive learning environment where students know their progress is valued. By using assessments to guide teaching and celebrate achievements, students feel motivated and engaged in their learning.

References:

- Airasian, P. W. (1997). Classroom Assessment. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Andrade, H. L., & Du, Y. (2005). Student Responses to Criteria-Referenced Self-Assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 30(2), 131-147.

- Beed, P. L., & Coutts, J. (2018). The Challenges and Opportunities of Differentiating Instruction for Inclusive Learning Environments in Higher Education. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 14(1), 23-41.

- Birenbaum, M., & Dochy, F. (1996). Alternatives in Assessment of Achievements, Learning Processes, and Prior Knowledge. Boston, MA: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-148.

- Boud, D., & Lee, A. (2005). Peer Learning as Pedagogic Discourse for Research Education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(5), 501-516.

- Brookhart, S. M. (2013). How to Create and Use Rubrics for Formative Assessment and Grading. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H., & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Handbook I: Cognitive Domain. New York, NY: Longmans, Green & Co.

- Burgstahler, S. (2015). Universal Design in Higher Education: From Principles to Practice. Harvard Education Press.

- Burgstahler, S., & Cory, R. (2008). Universal Design in Higher Education: Promising Practices. DO-IT, University of Washington.

- Cambridge, D. (2001). Portfolios and assessment: An introduction. Assessment in Education, 8(3), 265-268.

- Carey, T. (2016). A brief history of computerized adaptive testing. Research & Practice in Assessment, 11, 5-18.

- Carless, D. (2006). Differing perceptions in the feedback process. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 219-233.

- Carless, D. (2015). Excellence in University Assessment: Learning from Award-Winning Practice. Routledge.

- Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The Development of Student Feedback Literacy: Enabling Uptake of Feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315-1325.

- (2018). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.2. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Clariana, R. B., & Wallace, P. (2002). On-line assessment of learning in a human-computer interaction course. Computers & Education, 39(3), 271-280.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Adamson, F. (2010). Beyond Basic Skills: The Role of Performance Assessment in Achieving 21st Century Standards of Learning. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wilhoit, G., & Pittenger, L. (2014). Assessing deeper learning: A survey of performance assessment and mastery tracking tools. Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

- Davenport, J. H., & Davenport, J. L. (1985). Automated Feedback and Revision in Writing Instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(4), 395-407.

- Deng, L., & Yuen, A. H. K. (2011). Towards a framework for educational affordances of blogs. Computers & Education, 56(2), 441-451.

- Dreon, O., Kerper, R. M., & Landis, J. (2010). Digital storytelling: A tool for teaching and learning in the YouTube generation. Middle School Journal, 41(2), 220-227.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House.

- Falchikov, N., & Goldfinch, J. (2000). Student Peer Assessment in Higher Education: A Meta-Analysis Comparing Peer and Teacher Marks. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 287-322.

- Falchikov, N. (2005). Improving assessment through student involvement: Practical solutions for aiding learning in higher and further education. Psychology Press.

- Fluckiger, J., Vigil, Y. M., Pasco, R., & Danielson, K. (2010). Does the Sequence of Verbal and Visual Information Matter in Multimedia Learning? Journal of Educational Multimedia and Hypermedia, 19(1), 89-104.

- Gullickson, A. R., & Ellwein, M. C. (1985). Summative and Formative Assessment by Teachers. Journal of Educational Research, 78(5), 297-304.

- Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. Teachers College Press.

- Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin Press.

- Guskey, T. R., & Sparks, D. (2001). Linking professional development to improvements in student learning. ASCD.

- Guskey, T. R., & Yoon, K. S. (2009). What works in professional development? Phi Delta Kappan, 90(7), 495-500.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112.

- Heritage, M. (2007). Formative Assessment: What Do Teachers Need to Know and Do? Phi Delta Kappan, 89(2), 140-145.

- Hattie, J. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning. Routledge.

- Higgins, K. L., & Boone, R. (2019). Students’ Preferences for Accommodations in Online Courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 20(3), 1-15.

- Herrington, J., & Herrington, A. (2006). Authentic Mobile Learning in Higher Education. Paper presented at the 23rd Annual Conference of the Australasian Society for Computers in Learning in Tertiary Education, Sydney, Australia.

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2017). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review, 27.

- Light, G., Cox, R., & Calkins, S. (2009). Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: The Reflective Professional. SAGE Publications.

- Lonn, S., & Teasley, S. D. (2009). Saving time or innovating practice: Investigating perceptions and uses of Learning Management Systems. Computers & Education, 53(3), 686-694.

- Mercer, N., & Littleton, K. (2007). Dialogue and the Development of Children’s Thinking: A Sociocultural Approach. London, UK: Routledge.

- Meyer, A., Rose, D. H., & Gordon, D. (2014). Universal Design for Learning: Theory and Practice. CAST.

- McTighe, J., & O’Connor, K. (2005). Seven Practices for Effective Learning. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 10-17.

- Moon, J. A. (2001). Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice. London, UK: Routledge.

- National Center on Universal Design for Learning. (2011). Universal Design for Learning Guidelines version 2.0. Retrieved from http://udlguidelines.cast.org

- Nitko, A. J. (2001). Educational Assessment of Students (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane-Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self-regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 199-218.

- Pellegrino, J. W., Chudowsky, N., & Glaser, R. (Eds.). (2001). Knowing what students know: The science and design of educational assessment. National Academies Press.

- Popham, W. J. (2008). Transformative Assessment. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Popham, W. J. (2006). Assessment literacy for teachers: Faddish or fundamental? Theory into Practice, 45(1), 4-11.

- Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., & O’Donovan, B. (2011). Feedback: All that effort, but what is the effect? Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(6), 687-696.

- Rodriguez, M. C., & Baud, J. (2011). Beyond the Written Word: Developing a Multimodal Classroom Literacy. The Reading Teacher, 65(6), 416-426.

- Roediger, H. L., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006). Test-Enhanced Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249-255.

- Rose, D. H., & Meyer, A. (2002). Teaching Every Student in the Digital Age: Universal Design for Learning. ASCD.

- Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119-144.

- Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on Formative Feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153-189.

- Siemens, G., & Long, P. (2011). Penetrating the fog: Analytics in learning and education. EDUCAUSE Review, 46(5), 30-32.