Evidence-based practice improves patient outcomes and healthcare system return on investment: Findings from a scoping review

Affiliations.

- 1 Helene Fuld Health Trust National Institute for Evidence-Based Practice in Nursing & Healthcare, College of Nursing, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

- 2 St. John Fisher University, Wegmans School of Nursing, Rochester, New York, USA.

- 3 Sinai Hospital, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

- 4 Summa Health System, Akron, Ohio, USA.

- 5 The Ohio State University, College of Nursing, Columbus, Ohio, USA.

- 6 Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York, USA.

- 7 Family CareX, Denver, Colorado, USA.

- 8 Affiliate Faculty, VCU Libraries, Health Sciences Library, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Nursing, Richmond, Virginia, USA.

- PMID: 36751881

- DOI: 10.1111/wvn.12621

Background: Evidence-based practice and decision-making have been consistently linked to improved quality of care, patient safety, and many positive clinical outcomes in isolated reports throughout the literature. However, a comprehensive summary and review of the extent and type of evidence-based practices (EBPs) and their associated outcomes across clinical settings are lacking.

Aims: The purpose of this scoping review was to provide a thorough summary of published literature on the implementation of EBPs on patient outcomes in healthcare settings.

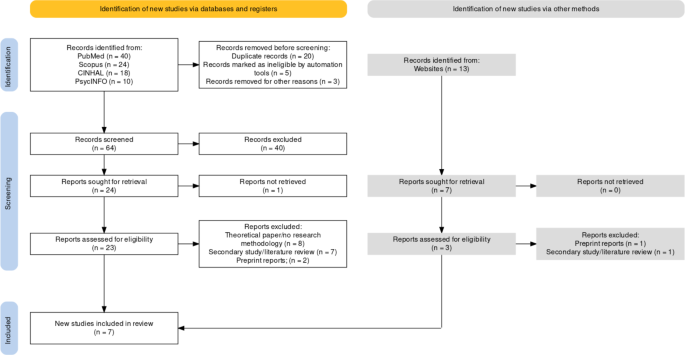

Methods: A comprehensive librarian-assisted search was done with three databases, and two reviewers independently performed title/abstract and full-text reviews within a systematic review software system. Extraction was performed by the eight review team members.

Results: Of 8537 articles included in the review, 636 (7.5%) met the inclusion criteria. Most articles (63.3%) were published in the United States, and 90% took place in the acute care setting. There was substantial heterogeneity in project definitions, designs, and outcomes. Various EBPs were implemented, with just over a third including some aspect of infection prevention, and most (91.2%) linked to reimbursement. Only 19% measured return on investment (ROI); 94% showed a positive ROI, and none showed a negative ROI. The two most reported outcomes were length of stay (15%), followed by mortality (12%).

Linking evidence to action: Findings indicate that EBPs improve patient outcomes and ROI for healthcare systems. Coordinated and consistent use of established nomenclature and methods to evaluate EBP and patient outcomes are needed to effectively increase the growth and impact of EBP across care settings. Leaders, clinicians, publishers, and educators all have a professional responsibility related to improving the current state of EBP. Several key actions are needed to mitigate confusion around EBP and to help clinicians understand the differences between quality improvement, implementation science, EBP, and research.

Keywords: evidence-based decision making; evidence-based practice; healthcare; patient outcomes; patient safety; return on investment.

© 2023 The Authors. Worldviews on Evidence-based Nursing published by Wiley Periodicals LLC on behalf of Sigma Theta Tau International.

Publication types

- Systematic Review

- Delivery of Health Care*

- Evidence-Based Practice* / methods

- Quality Improvement

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Total quality management in the health-care context: integrating the literature and directing future research

Majdi m alzoubi, zm al-hamdan.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: KS HayatiDepartment of Community Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, University Putra Malaysia, UPM Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, 43400, MalaysiaEmail [email protected]

Received 2018 Dec 4; Accepted 2019 Jul 11; Collection date 2019.

This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ ). By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed. For permission for commercial use of this work, please see paragraphs 4.2 and 5 of our Terms ( https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php ).

Synergistic integration of predictors and elements that determine the success of total quality management (TQM) implementations in hospitals has been the bane of theoretical development in the TQM research area. Thus, this paper aims to offer a systematic literature review to provide a foundation on which research on TQM can be built and to identify the predictors of successful TQM in the health-care context.

Materials and methods

A systematic literature survey was adopted in this paper, involving the review of 25 relevant researched articles found in the databases Science Direct, EBSCO, MEDLINE, CINAHL and PubMed.

The systematic literature survey reveals five variables to be core predictors of TQM, signifying how important these variables are in the successful implementation of TQM in the health-care context. Also, it is revealed that the identified core predictors have positive effects on an improved health-care system. However, the systematic survey of the literature reveals a dearth of studies on TQM in the health-care context.

As TQM has become an important management approach for advancing effectiveness in the health-care sector, this kind of research is of value to researchers and managers. Stakeholders in the health sectors should introduce and implement TQM in hospitals and clinics. Nevertheless, this study has limitations, including that the databases and search engines adopted for the literature search are not exhaustive.

Keywords: total quality management, total quality management implementation, health care, commitment, systematic literature review, critical success factors

Introduction

Given the snowballing global economic competition and other external pressures, organizations have been compelled to pursue enduring quality and quality management which will, in turn, enhance their competitive advantage. Quality as a concept has metamorphosed over the years, and it involves objective quality bordering on the characteristics and quality of goods and services that meet implicit and explicit customer demands. It also includes subjective quality which denotes the capability to produce goods and services in the best, effective and efficient manner. 1

Looking at the health-care context, quality has always been aimed at since the time of Florence Nightingale. 2 Given that quality assurance is a requisite for economic survival, 3 and that it is an ethical, legal and social rights matter, 4 the health sector has been worried about it for more than a decade .2 Quality assurance is significant as it concerns customer satisfaction and the reduction of risks connected with health care to a minimum. 5 In the present time, health care has become a developing profession with an approach to care quality via the appraisal and regulation of structure, process and care result components. 6

Given the ever-increasing competitive and dynamic environment in which hospitals operate, and the need to augment hospitals’ performance and health-care quality, researchers 2 , 7 – 9 have conducted considerable research on enhancement of health-care quality. Moreover, given that nurse performance is crucial to the overall performance of the hospital and effective health-care system, there has been a research focus on nurse performance. 7 Nurses represent a large percentage of the health workers in any hospital. Nurses would play a significant role in the implementation of any intervention programs introduced by any hospital.

Moreover, research 8 – 11 has shown that the health-care system is facing a myriad of challenges which include high care cost, swiftly increasing dependence on technology, economic pressure on health organizations, reduction in health-care quality, 8 , 10 fulfillment of patients’ needs, 9 augmented numbers of patients who are suffering from multiple illnesses, increased demand for high-quality care, increased health-care costs and cost-containment pressures (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [OECD] 2007). 11 Some studies have indicated that an active way of surmounting health-care challenges is through an intervention program that will border on quality management (eg, total quality management [TQM]). 12

TQM is a system implemented by the management of an organization to achieve the satisfaction of customers/patients .13 The importance of TQM as a strategy to improve organizational performance has grown in this era of globalization. 14 Numerous research has revealed the role of TQM in the enrichment of system quality and enhancement of both employee and organizational performance. TQM is known for continuous quality improvement, quality management and total quality control. 10 TQM is held to be an innovative approach to the management of organizations. In the medical sector, TQM integrates quality orientation in all processes and procedures in health-care delivery .15 It is now being widely adopted in the medical sector of many countries. The research by Vituri and Évora 2 indicates that the literature on TQM in health sectors reveals that TQM has been fully adopted in some health institutions.

The implementation of TQM, upon which the success of TQM hinges, is intricate and complex; it depends on a good combination of certain predictors (ie, critical success factors [CSF]), and its benefits are difficult to accomplish .16 Different means of integrating predictors of TQM, although inconsistent, have emerged in the literature. 17 Some predictors have been considered crucial to TQM success, 18 and thus the exceptional predictors which can be adopted by organizations, irrespective of their industry, type, size or location. 19 These predictors are regarded as the determinants of firm performance via effective implementation of TQM.

Nevertheless, synergistic integration of predictors and elements, otherwise known as CSFs and which determine the success of TQM implementation, has been the bane of theoretical development in the TQM research area. Some of these predictors have been reported, by extant studies, 20 to have a positive impact on performance.

Likewise, substantive problems exist and can hamper theoretical development in the research area. The literature lacks foundation and structure on which the research on TQM in the health-care context is based, and connections between studies on TQM in the health-care context can hardly be drawn. The current state of extant research on TQM in the health-care context indicates that there is a need for more research in the area. 21 New knowledge development regarding identification of fitting predictors for successful TQM that enhance effectiveness in the health-care sector should be developed and where further research needs to be done should be identified.

Considering the extant works on a systematic literature review on predictors of TQM, two English written studies 14 , 22 are discernible, but Hietschold et al 14 focused on CSFs of TQM in general contexts while Aquilani et al 22 focused on the identification of TQM research, implementation of TQM research and impact-of-TQM-on-performance research in general contexts. Besides these two studies, no studies have focused on the systematic literature survey of predictors/elements of TQM in the health-care context.

Therefore, undertaking a systematic literature review in this aspect of research is germane, and this paper is poised to do as such. This paper conducts a systematic literature survey to provide a foundation stone on which research on TQM in the health-care context can be built, to evaluate the current state of evidence for TQM in the health-care context, to reveal inadequacies in the literature and to point to where further research needs to be done.

This research is guided by the following research question: what are the predictors of successful TQM in the health-care context between the period of 2005 and 2016? Like the two previous studies on a systematic literature review of TQM, this paper adopts and applies the three core steps of planning, execution and reporting that constitute a systematic literature survey. 23

This research seeks to obtain the most important predictors of successful TQM in the health-care context. This includes the review of published peer-reviewed works in English-language journals, which were published between 2005 and 2016. The literature was sourced from Science Direct, EBSCO, MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online), CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) and PubMed (US National Library of Medicine).

As part of the process of systematic literature analysis in this paper, a structured search of the academic literature was conducted to find published articles that identified TQM, total quality management, implementation, CSFs, health care and nursing. The keywords used in the search are TQM, total quality management, implementation, critical success factors, health care and nursing.

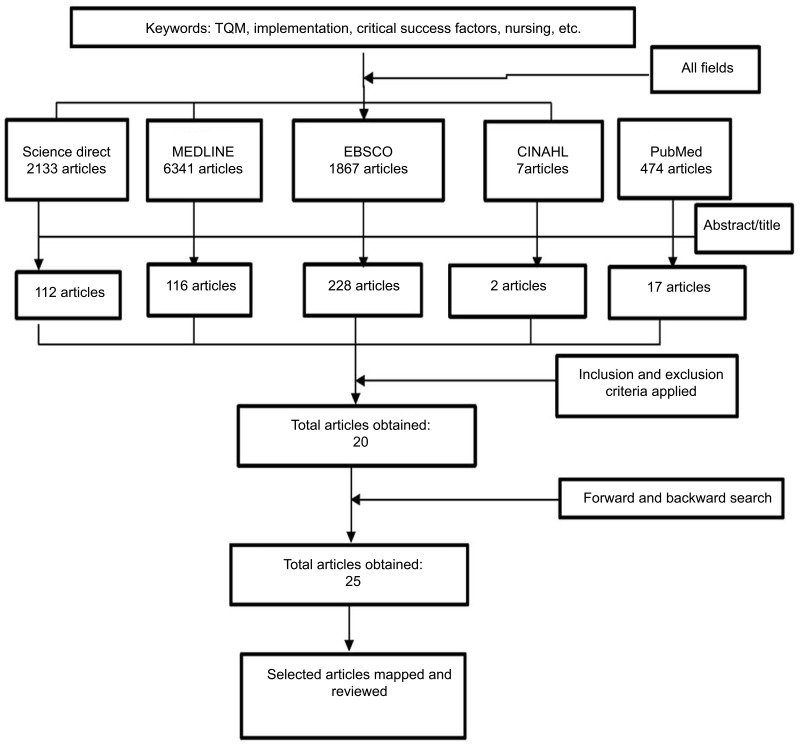

As presented in Figure 1 , a search of Science Direct, MEDLINE, EBSCO, CINAHL and PubMed yielded 2133, 6341, 1867, 7 and 474 articles, respectively. Then, repeated citations, dissertations and case studies were deleted. Via reading of the title and abstract, the remaining articles were narrowed down by relevance. Only peer-reviewed academic and practice articles that focus on total quality management, implementation, CSFs health care and nursing were selected. This exercise yielded a total of 475 articles which were published between 2005 and 2016.

Consort flow chart of systematic review method.

Abbreviation: TQM, total quality management.

Furthermore, inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to narrow down the yielded articles. The inclusion criteria involved articles which were written in English language and published between 2005 and 2016, articles that dwell on implementation and critical factors clearly, articles from any geographical location which examined TQM, TQM principles, TQM tools and methods in the context of the health-care sector, and TQM studies that used a quantitative research approach and quasi-experimental research design. The exclusion criteria involved articles which are written in non-English language and published before 2005 or after 2016, studies in which the population and sample were not health-care workers practicing inside hospitals, gray literature or works that are not published in a peer-reviewed journal, dissertations/theses, proceedings, published abstracts, studies with qualitative research methods, and commentary articles written to convey opinion or stimulate research or discussion, with no research component. By employing these inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 articles were generated. Moreover, to guarantee all-inclusiveness and to widen the scope of the review, a forward and backward search of citations in articles was conducted. This was recognized via the database searches, and 25 articles were finally selected. Thereafter, the 25 generated articles were fully perused.

Likewise, for exhaustive research, the approach adopted in this paper also involved the identification and measurement of predictors (CSFs) of TQM. This was done by identifying the most common or important predictors in the selected 25 works that analyze the existing models and/or scales in other contexts, industries or countries. It also includes recognition of the papers that investigate the influence of TQM implementation and/or the impact of predictors of TQM on performance. Additionally, for a proper review of the selected works, adequate plotting of the development of the line of reasoning, integrating and synthesizing the studies, authors, study design, study population, variables, measures of variables and findings of each selected article were identified and noted down. Figure 1 represents the consort flow chart of the systematic review method.

Findings and discussion

Altogether, 25 researched articles were eventually reviewed. All of the selected 25 articles are based on empirical evidence, although a possible limitation of this systematic review strategy might be the exclusion of qualitative studies in the research. Based on Table 1 , five predictors were identified. These are presented in Table 2 .

Matrix of the reviewed literature

Abbreviations: HR, human resources; TQM, total quality management.

TQM predictors in the reviewed studies

The researched literature on predictors of successful TQM implementation was found to be from various countries but in the same health sector. While some predictors adopted by a few of the researched studies were identified, the most frequent and core predictors were identified and considered. As depicted in Table 2 , education and training, continuous quality improvement, patient focus/satisfaction, top management commitment and teamwork appear to be the core predictors (CSFs) in this review. This finding validates how important these variables are in the successful implementation of TQM in the health-care context.

It is noteworthy that the core predictors (ie, education and training, continuous quality improvement, patient focus/satisfaction, top management commitment and teamwork) identified in this study were among the variables found to be central and frequently used CSFs in the previous systematic-review-based studies. 14 , 21 This validates and confirms the findings of the previous studies.

Moreover, it is found that the most adopted research method in TQM in the health-care context is cross-sectional research; 56% of the reviewed researched articles 41 – 46 used a cross-sectional research design, but 32% of the studies employed a quasi-experimental research approach. This indicates that there is still a need for more research on TQM in the health-care context which will adopt a quasi-experimental research approach, because quasi-experimental research design can be very useful in recognizing general trends from the results, and reduces the difficulty and ethical worries that may be connected with the pre-selection and random assignment of test subjects. On the geographical location aspect, the result of this analysis showed that 28% of the reviewed studies were conducted in Iran while 20% of the reviewed studies were conducted in Jordan; 12% and 8% of the reviewed studies were conducted in Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, respectively. The other studies, 4% each, came from India, Namibia, Turkey, the United States, France and Mauritius.

With regards to the influence of predictors on performance in the researched studies, it is found that all of the selected articles 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 ,. 51 that examined the effects of the core predictors (continuous quality improvement, education and training, patient focus/satisfaction, top management commitment and teamwork) of TQM indicate a positive effect of TQM in the health-care sector.

More so, the findings of this review signify that predictors of TQM implementation will result in higher levels of nurse performance .51 In addition, the literature and empirical evidence have shown that TQM in an organizational process always results in better performance of the organization. TQM focuses on patient satisfaction, organization problem identification, building and promotion of open decision-making among employees. It embraces a holistic strategy that gives room for every worker to share responsibility for the quality of the work done. It makes use of analytical mechanisms, such as flow and statistical charts and checksheets, to gather information about activities in an organization. 52 In the medical sector, TQM aims at embedding orientation of quality in all processes and procedures in the delivery of health services .15

Nevertheless, this literature survey is not an exhaustive review of the literature on TQM as it solely focused on the effect of TQM. Future research should widen the scope of this paper by including studies conducted in other contexts (eg, education, manufacturing, etc) and studies that use different research methods (eg, longitudinal research method, randomized control trial method). While TQM predictors have increased in number to reach a total of 59 TQM practices, 21 TQM predictors in the context of health care are few but growing. Investigating the nature of TQM predictors and the methods used in examining them indicates that researchers may have been keen in searching for new predictors instead of trying to cluster them and identify those that are critical for successful TQM implementation. In addition, research on TQM predictors in the health-care sector is scanty, as noted previously.

Practically, given the identified core TQM predictors in this study, it is evident that hospitals’ management should consider entrenchment of continuous quality improvement, education and training, patient focus/satisfaction top management commitment and teamwork in the implementation of TQM, which will consequently enhance hospital performance. Given that TQM predictors are many and some of them have been considered core in several specific contexts, industries, dimensions, etc, it is held that stakeholders in different sectors/industries should begin to identify the most vital TQM practices that suit their situations, goals, strategies and expected performances.

Conclusion and recommendations

As TQM has become an important management approach for advancing performance, this kind of research is of value to researchers and managers. Nevertheless, this study has limitations, including that the databases and search engines adopted for the literature search are not exhaustive. Although a good number of keywords are used, there can be other likely keywords that can be included.

This work has contributed to the enrichment of the relevant literature and made theoretical and methodological contributions. It has provided a foundation on which research on TQM can be built via review of the work done between 2005 and 2016, plotting the development of the line of reasoning, and integration and synthesis of studies from TQM in the health-care context. It has also contributed by evaluating the current state of evidence regarding TQM, indicating inadequacies in the literature and pointing to where further research needs to be done. Thus, it contributes to the present body of knowledge as well as the research on TQM in the health-care context.

This work has also established that the most adopted research method in health-care-based TQM is cross-sectional research, followed by quasi-experimental research, and the researched studies were mostly conducted in Asia. The findings of the researched literature indicate a positive effect of TQM in the health-care context, indicating that TQM implementation, which contains the identified core predictors, will result in higher levels of performance. Furthermore, TQM implementation can help health-care professionals to gain more qualified behaviors with total commitment to work toward handling the patients, which in the long run will augment their performance.

The findings of the reviewed studies indicate how it would be useful for stakeholders in the health sectors to introduce and implement TQM in the hospitals and clinics, as this would enhance the performance of the health workers and consequently improve organizational performance. Given the limitations of this work, it is sufficed to suggest that future research should widen the scope of this paper by including studies conducted in other contexts and studies that use different research methods, and it should also develop a comprehensive TQM taxonomy to explain how and why TQM practices coalesce within systems that facilitate higher performance.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

- 1. Bonechi L, Carmignani G, Mirandola R. La Gestione Della Qualità Nelle Organizzazioni-dalla Conformità All’eccellenza Gestionale . Edizioni Plus srl; 2004. [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Vituri DW, Évora YDM. Total Quality Management and hospital nursing: an integrative literature review. Rev Bras Enferm . 2015;68(5):945–952. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167.2015680525i [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Antunes M, Sfakiotakis E. Effect of high temperature stress on ethylene biosynthesis, respiration and ripening of ‘Hayward’kiwifruit. Postharvest Biol Technol . 2000;20(3):251–259. doi: 10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00136-8 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Adami C, Ofria C, Collier TC. Evolution of biological complexity. Proc Natl Acad Sci . 2000;97(9):4463–4468. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4463 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. Padilha KG. Iatrogenic occurrences and the quality focus. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem . 2001;9(5):91–96. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692001000500014 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Haddad M, Évora YDM. Qualidade da assistência de enfermagem: a opinião do paciente internado em hospital universitário público. Ciênc Cuid Saúde . 2008;7:45–52. doi: 10.4025/cienccuidsaude.v7i0.6559 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. Wright TA, Bonett DG. The moderating effects of employee tenure on the relation between organizational commitment and job performance: a meta-analysis. J Appl Psychol . 2002;87(6):1183. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.6.1183 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van Den Heede K, et al. Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ . 2012;344:e1717. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1717 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Chang C-S, Chen S-Y, Lan Y-T. Service quality, trust, and patient satisfaction in interpersonal-based medical service encounters. BMC Health Serv Res . 2013;13(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-438 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. McClellan M, Rivlin A. Improving Health while Reducing Cost Growth: What is Possible . Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform at Brookings; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving Performance . World Health Organization; 2000. [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Cummings TG, Worley CG. Organization Development and Change . Cengage learning; 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Srima S, Wannapiroon P, Nilsook PJP-S, Sciences B. Design of total quality management information system (TQMIS) for model school on best practice. 2015;174:2160–2165. [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Hietschold N, Reinhardt R, Gurtner S. Measuring critical success factors of TQM implementation successfully–a systematic literature review. Int J Prod Res . 2014;52(21):6254–6272. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2014.918288 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. MoHSW T. Implementation Guidelines for 5S-KAIZEN-TQM Approaches in Tanzania . Dar es Salaam (Tanzania): Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Mohammad Mosadegh Rad A. The impact of organizational culture on the successful implementation of total quality management. TQM Magazine . 2006;18(6):606–625. doi: 10.1108/09544780610707101 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Ismail Salaheldin S. Critical success factors for TQM implementation and their impact on performance of SMEs. Int J Prod Perform Manage . 2009;58(3):215–237. doi: 10.1108/17410400910938832 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Kumar S, Ghildayal NS, Shah RN. Examining quality and efficiency of the US healthcare system. Int J Health Care Qual Assur . 2011;24(5):366–388. doi: 10.1108/09526861111139197 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Zairi M, Alsughayir AA. The adoption of excellence models through cultural and social adaptations: an empirical study of critical success factors and a proposed model. Total Qual Manage Bus Excellence . 2011;22(6):641–654. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2011.580654 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Sadikoglu E, Olcay H. The effects of total quality management practices on performance and the reasons of and the barriers to TQM practices in Turkey. Adv Decis Sci . 2014;2014:1–17. doi: 10.1155/2014/537605 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Aquilani B, Silvestri C, Ruggieri A, Gatti C. A systematic literature review on total quality management critical success factors and the identification of new avenues of research. Tqm J . 2017;29(1):184–213. doi: 10.1108/TQM-01-2016-0003 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 22. Aquilani B, Silvestri C, Ioppolo G, Ruggieri A. The challenging transition to bio-economies: Towards a new framework integrating corporate sustainability and value co-creation. J Clean Prod . 2018;172:4001–4009. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.03.153 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 23. Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P. Towards a methodology for developing evidence‐informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manage . 2003;14(3):207–222. doi: 10.1111/bjom.2003.14.issue-3 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 24. Irfan S, Ijaz A, Kee D, Awan M. Improving operational performance of public hospital in Pakistan: A TQM based approach. World Appl Sci J . 2012;19(6):904–913. [ Google Scholar ]

- 25. Mrayyan MT, Al‐Faouri I. Predictors of career commitment and job performance of Jordanian nurses. J Nurs Manag . 2008;16(3):246–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00797.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 26. Danial Z. Effect of Total Quality Management in Determining the Educational Needs of Critical Wards Nurses . 2009. [ Google Scholar ]

- 27. Awases MH, Bezuidenhout MC, Roos JH. Factors affecting the performance of professional nurses in Namibia. Curationis . 2013;36(1):1–8. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v36i1.108 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 28. Al-Ahmadi H. Factors affecting performance of hospital nurses in Riyadh Region, Saudi Arabia. Int J Health Care Qual Assur . 2009;22(1):40–54. doi: 10.1108/09526860910927943 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 29. Kim K, Han Y, Kwak Y, Kim J-S. Professional quality of life and clinical competencies among Korean nurses. Asian Nurs Res . 2015;9(3):200–206. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2015.03.002 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 30. AbuAlRub RF, AL‐ZARU IM. Job stress, recognition, job performance and intention to stay at work among Jordanian hospital nurses. J Nurs Manag . 2008;16(3):227–236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2007.00810.x [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 31. Güleryüz G, Güney S, Aydın EM, Aşan Ö. The mediating effect of job satisfaction between emotional intelligence and organisational commitment of nurses: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud . 2008;45(11):1625–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.02.004 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 32. Lashgari MH, Arefanian S, Mohammadshahi A, Khoshdel AR. Effects of the total quality management implication on patient satisfaction in the Emergency Department of Military Hospitals. J Arch Mil Med . 2015;3(1). doi: 10.5812/jamm [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 33. Navipour H, Nayeri ND, Hooshmand A, Zargar MT. An investigation into the effects of quality improvement method on patients’ satisfaction: a semi experimental research in Iran. Acta Med Iran . 2011;49(1):38–43. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 34. Mosadeghrad AM. Developing and validating a total quality management model for healthcare organisations. TQM J . 2015;27(5):544–564. doi: 10.1108/TQM-04-2013-0051 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 35. Mohammad Mosadeghrad A. Why TQM does not work in Iranian healthcare organisations. Int J Health Care Qual Assur . 2014;27(4):320–335. doi: 10.1108/IJHCQA-11-2012-0110 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 36. Mosadeghrad AM. Implementing strategic collaborative quality management in healthcare sector. Int J Strat Change Manage . 2012;4(3/4):203–228. doi: 10.1504/IJSCM.2012.051846 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 37. Jones KJ, Skinner AM, High R, Reiter-Palmon R. A theory-driven, longitudinal evaluation of the impact of team training on safety culture in 24 hospitals. BMJ Qual Saf . 2013;22(5):394–404. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000939 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 38. Ullah JH, Ahmed R, Malik JI, Khan MA. Outcome of 7-S, TQM technique for healthcare waste management. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak . 2011;21(12):731–734. doi: 12.2011/JCPSP.731734 [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 39. Padma P, Rajendran C, Sai Lokachari P. Service quality and its impact on customer satisfaction in Indian hospitals: Perspectives of patients and their attendants. Benchmarking . 2010;17(6):807–841. doi: 10.1108/14635771011089746 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 40. Ramseook-Munhurrun P, Munhurrun V, Panchoo A. Total Quality Management Adoption in a Public Hospital: Evidence from Mauritius . 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- 41. Alaraki MS. The impact of critical total quality management practices on hospital performance in the ministry of health hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Qual Manage Healthcare . 2014;23(1):59–63. doi: 10.1097/QMH.0000000000000018 [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 42. Al-Shdaifat EA. Implementation of total quality management in hospitals. J Taibah Univ Med Sci . 2015;10(4):461–466. doi: 10.1016/j.jtumed.2015.05.004 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 43. Larber M, Savis S. Factors affecting nurses organizational commitment. Obzornik Zdravstvene Nege . 2014;48(4):294–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- 44. Duggirala M, Rajendran C, Anantharaman R. Patient-perceived dimensions of total quality service in healthcare. Benchmarking . 2008;15(5):560–583. doi: 10.1108/14635770810903150 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 45. Naser Alolayyan M, Anuar Mohd Ali K, Idris F. The influence of total quality management (TQM) on operational flexibility in Jordanian hospitals: medical workers’ perspectives. Asian J Qual . 2011;12(2):204–222. doi: 10.1108/15982681111158751 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 46. Sweis RJ, Al-Mansour A, Tarawneh M, Al-Dweik G. The impact of total quality management practices on employee empowerment in the healthcare sector in Saudi Arabia: a study of King Khalid Hospital. Int J Prod Qual Manage . 2013;12(3):271–286. doi: 10.1504/IJPQM.2013.056149 [ DOI ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 47. Kumar R, Somrongthong R, Ahmed J. Impact of waste management training intervention on knowledge, attitude and practices of teaching hospital workers in Pakistan. Pak J Med Sci . 2016;32(3):705. doi: 10.12669/pjms.323.9903 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 48. Sagy M. Optimizing patient care processes in a children’s hospital using Six Sigma. JCOM . 2009;16:9. [ Google Scholar ]

- 49. Denker AG. Transformational Leadership in Nursing: A Pilot Nurse Leader Development Program . 2014. [ Google Scholar ]

- 50. François P, Vinck D, Labarère J, Reverdy T, Peyrin J-C. Assessment of an intervention to train teaching hospital care providers in quality management. BMJ Qual Saf . 2005;14(4):234–239. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2004.011924 [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 51. El-Tohamy AE-MA, Al Raoush AT. The impact of applying total quality management principles on the overall hospital effectiveness: an empirical study on the HCAC accredited governmental hospitals in Jordan. Eur Sci J . 2015;11(10). [ Google Scholar ]

- 52. Kaluzny AD, McLaughlin CP, Simpson K. Applying total quality management concepts to public health organizations. Public Health Rep . 1992;107(3):257. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (446.8 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Busse R, Klazinga N, Panteli D, et al., editors. Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies [Internet]. Copenhagen (Denmark): European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2019. (Health Policy Series, No. 53.)

Improving healthcare quality in Europe: Characteristics, effectiveness and implementation of different strategies [Internet].

3 measuring healthcare quality.

Wilm Quentin , Veli-Matti Partanen , Ian Brownwood , and Niek Klazinga .

3.1. Introduction

The field of quality measurement in healthcare has developed considerably in the past few decades and has attracted growing interest among researchers, policy-makers and the general public (Papanicolas & Smith, 2013 ; EC, 2016 ; OECD, 2019 ). Researchers and policy-makers are increasingly seeking to develop more systematic ways of measuring and benchmarking quality of care of different providers. Quality of care is now systematically reported as part of overall health system performance reports in many countries, including Australia, Belgium, Canada, Italy, Mexico, Spain, the Netherlands, and most Nordic countries. At the same time, international efforts in comparing and benchmarking quality of care across countries are mounting. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the EU Commission have both expanded their efforts at assessing and comparing healthcare quality internationally (Carinci et al., 2015 ; EC, 2016 ). Furthermore, a growing focus on value-based healthcare (Porter, 2010 ) has sparked renewed interest in the standardization of measurement of outcomes (ICHOM, 2019 ), and notably the measurement of patient-reported outcomes has gained momentum (OECD, 2019 ).

The increasing interest in quality measurement has been accompanied and supported by the growing ability to measure and analyse quality of care, driven, amongst others, by significant changes in information technology and associated advances in measurement methodology. National policy-makers recognize that without measurement it is difficult to assure high quality of service provision in a country, as it is impossible to identify good and bad providers or good and bad practitioners without reliable information about quality of care. Measuring quality of care is important for a range of different stakeholders within healthcare systems, and it builds the basis for numerous quality assurance and improvement strategies discussed in Part II of this book. In particular, accreditation and certification ( see Chapter 8 ), audit and feedback ( see Chapter 10 ), public reporting ( see Chapter 13 ) and pay for quality ( see Chapter 14 ) rely heavily on the availability of reliable information about the quality of care provided by different providers and/or professionals. Common to all strategies in Part II is that without robust measurement of quality, it is impossible to determine the extent to which new regulations or quality improvement interventions actually work and improve quality as expected, or if there are also adverse effects related to these changes.

This chapter presents different approaches, frameworks and data sources used in quality measurement as well as methodological challenges, such as risk-adjustment, that need to be considered when making inferences about quality measures. In line with the focus of this book ( see Chapter 1 ), the chapter focuses on measuring quality of healthcare services, i.e. on the quality dimensions of effectiveness, patient safety and patient-centredness. Other dimensions of health system performance, such as accessibility and efficiency, are not covered in this chapter as they are the focus of other volumes about health system performance assessment ( see , for example, Smith et al., 2009 ; Papanicolas & Smith, 2013 ; Cylus, Papanicolas & Smith, 2016 ). The chapter also provides examples of quality measurement systems in place in different countries. An overview of the history of quality measurement (with a focus on the United States) is given in Marjoua & Bozic ( 2012 ). Overviews of measurement challenges related to international comparisons are provided by Forde, Morgan & Klazinga ( 2013 ) and Papanicolas & Smith ( 2013 ).

3.2. How can quality be measured? From a concept of quality to quality indicators

Most quality measurement initiatives are concerned with the development and assessment of quality indicators (Lawrence & Olesen, 1997 ; Mainz, 2003 ; EC, 2016 ). Therefore, it is useful to step back and reflect on the idea of an indicator more generally. In the social sciences, an indicator is defined as “a quantitative measure that provides information about a variable that is difficult to measure directly” (Calhoun, 2002 ). Obviously, quality of care is difficult to measure directly because it is a theoretical concept that can encompass different aspects depending on the exact definition and the context of measurement.

Chapter 1 has defined quality of care as “the degree to which health services for individuals and populations are effective, safe and people-centred”. However, the chapter also highlighted that there is considerable confusion about the concept of quality because different institutions and people often mean different things when using it. To a certain degree, this is inevitable and even desirable because quality of care does mean different things in different contexts. However, this context dependency also makes clarity about the exact conceptualization of quality in a particular setting particularly important, before measurement can be initiated.

In line with the definition of quality in this book, quality indicators are defined as quantitative measures that provide information about the effectiveness, safety and/or people-centredness of care. Of course, numerous other definitions of quality indicators are possible (Mainz, 2003 ; Lawrence & Olesen, 1997 ). In addition, some institutions, such as the National Quality Forum (NQF) in the USA, use the term quality measure instead of quality indicator . Other institutions, such as the NHS Indicator Methodology and Assurance Service and the German Institute for Quality Assurance and Transparency in Health Care (IQTIG), define further attributes of quality indicators (IQTIG, 2018 ; NHS Digital, 2019a ). According to these definitions, quality indicators should provide:

- a quality goal, i.e. a clear statement about the intended goal or objective, for example, inpatient mortality of patients admitted with pneumonia should be as low as possible;

- a measurement concept, i.e. a specified method for data collection and calculation of the indicator, for example, the proportion of inpatients with a primary diagnosis of pneumonia who died during the inpatient stay; and

- an appraisal concept, i.e. a description of how a measure is expected to be used to judge quality, for example, if inpatient mortality is below 10%, this is considered to be good quality.

Often the terms measures and indicators are used interchangeably. However, it makes sense to reserve the term quality indicator for measures that are accompanied by an appraisal concept (IQTIG, 2018 ). This is because measures without an appraisal concept are unable to indicate whether measured values represent good or bad quality of care. For example, the readmission rate is a measure for the number of readmissions. However, it becomes a quality indicator if a threshold is defined that indicates “higher than normal” readmissions, which could, in turn, indicate poor quality of care. Another term that is frequently used interchangeably with quali ty indicator , in particular in the USA, is quality metric . However, a quality metric also does not necessarily define an appraisal concept, which could potentially distinguish it from an indicator. At the same time, the term qua l ity metric is sometimes used more broadly for an entire system that aims to evaluate quality of care using a range of indicators.

Operationalizing the theoretical concept of quality by translating it into a set of quality indicators requires a clear understanding of the purpose and context of measurement. Chapter 2 has introduced a five-lens framework for describing and classifying quality strategies. Several of these lenses are also useful for better understanding the different aspects and contexts that need to be taken into account when measuring healthcare quality. First, it is clear that different indicators are needed to assess the three dimensions of quality, i.e. effectiveness, safety and/or patient-centredness, because they relate to very different concepts, such as patient health, medical errors and patient satisfaction.

Secondly, quality measurement has to differ depending on the concerned function of the healthcare system, i.e. depending on whether one is aiming to measure quality in preventive, acute, chronic or palliative care. For example, changes in health outcomes due to preventive care will often be measurable only after a long time has elapsed, while they will be visible more quickly in the area of acute care. Thirdly, quality measurement will vary depending on the target of the quality measurement initiative, i.e. payers, provider organizations, professionals, technologies and/or patients. For example, in some contexts it might be useful to assess the quality of care received by all patients covered by different payer organizations (for example, different health insurers or regions) but more frequently quality measurement will focus on care provided by different provider organizations. In international comparisons, entire countries will constitute another level or target of measurement.

In addition, operationalizing quality for measurement will always require a focus on a limited set of quality aspects for a particular group of patients. For example, quality measurement may focus on patients with hip fracture treated in hospitals and define aspects of care that are related to effectiveness (for example, surgery performed within 24 hours of admission), safety (for example, anticoagulation to prevent thromboembolism), and/or patient-centredness of care (for example, patient was offered choice of spinal or general anaesthesia) (Voeten et al., 2018 ). However, again, the choice of indicators – and also potentially of different appraisal concepts for indicators used for the same quality aspects – will depend on the exact purpose of measurement.

3.3. Different purposes of quality measurement and users of quality information

It is useful to distinguish between two main purposes of quality measurement: The first purpose is to use quality measurement in quality assurance systems as a summative mec h anism for external accountability and verification. The second purpose is to use quality measurement as a formative mechanism for quality improvement. Depending on the purpose, quality measurement systems face different challenges with regard to indicators, data sources and the level of precision required.

Table 3.1 highlights the differences between quality assurance and quality improvement (Freeman, 2002 ; Gardner, Olney & Dickinson, 2018 ). Measurement for quality assurance and accountability is focused on identifying and overcoming problems with quality of care and assuring a sufficient level of quality across providers. Quality assurance is the focus of many external assessment strategies ( see also Chapter 8 ), and providers of insufficient quality may ultimately lose their licence and be prohibited from providing care. Assuring accountability is one of the main purposes of public reporting initiatives ( see Chapter 13 ), and measured quality of care may contribute to trust in healthcare services and allow patients to choose higher-quality providers.

The purpose of quality measurement: quality assurance versus quality improvement.

Quality measurement for quality assurance and accountability makes summative judgements about the quality of care provided. The idea is that “real” differences will be detected as a result of the measurement initiative. Therefore, a high level of precision is necessary and advanced statistical techniques may need to be employed to make sure that detected differences between providers are “real” and attributable to provider performance. Otherwise, measurement will encounter significant justified resistance from providers because its potential consequences, such as losing the licence or losing patients to other providers, would be unfair. Appraisal concepts of indicators for quality assurance will usually focus on assuring a minimum quality of care and identifying poor-quality providers. However, if the purpose is to incentivize high quality of care through pay for quality initiatives, the appraisal concept will likely focus on identifying providers delivering excellent quality of care.

By contrast, measurement for quality improvement is change oriented and quality information is used at the local level to promote continuous efforts of providers to improve their performance. Indicators have to be actionable and hence are often more process oriented. When used for quality improvement, quality measurement does not necessarily need to be perfect because it is only informative. Other sources of data and local information are considered as well in order to provide context for measured quality of care. The results of quality measurement are only used to start discussions about quality differences and to motivate change in provider behaviour, for example, in audit and feedback initiatives ( see Chapter 10 ). Freeman ( 2002 ) sums up the described differences between quality improvement and quality assurance as follows: “Quality improvement models use indicators to develop discussion further, assurance models use them to foreclose it.”

Different stakeholders in healthcare systems pursue different objectives and as a result they have different information needs (Smith et al., 2009 ; EC, 2016 ). For example, governments and regulators are usually focused on quality assurance and accountability. They use related information mostly to assure that the quality of care provided to patients is of a sufficient level to avoid harm – although they are clearly also interested in assuring a certain level of effectiveness. By contrast, providers and professionals are more interested in using quality information to enable quality improvement by identifying areas where they deviate from scientific standards or benchmarks, which point to possibilities for improvement ( see Chapter 10 ). Finally, patients and citizens may demand quality information in order to be assured that adequate health services will be available in case of need and to be able to choose providers of good-quality care ( see Chapter 13 ). The stakeholders and their purposes of quality measurement have, of course, an important influence on the selection of indicators and data needs ( see below).

While the distinction between quality assurance and quality improvement is useful, the difference is not always clear-cut. First, from a societal perspective, quality assurance aims at stamping out poor-quality care and thus contributes to improving average quality of care. Secondly, proponents of several of the strategies that are included under quality assurance in Table 3.1 , such as external assessment ( see also Chapter 8 ) or public reporting ( see also Chapter 13 ), in fact claim that these strategies do contribute to improving quality of care and assuring public trust in healthcare services. In fact, as pointed out in the relevant chapters, the rationale of external assessment and public reporting is that these strategies will lead to changes within organizations that will ultimately contribute to improving quality of care. Clearly, there also need to be incentives and/or motivations for change, i.e. while internal quality improvement processes often rely on professionalism, external accountability mechanisms seek to motivate through external incentives and disincentives – but this is beyond the scope of this chapter.

3.4. Types of quality indicators

There are many options for classifying different types of quality indicators (Mainz, 2003 ). One option is to distinguish between rate-based indicators and simple count-based indicators, usually used for rare “sentinel” events. Rate-based indicators are the more common form of indicators. They are expressed as proportions or rates with clearly defined numerators and denominators, for example, the proportion of hip fracture patients who receive antibiotic prophylaxis before surgery. Count-based indicators are often used for operationalizing the safety dimension of quality and they identify individual events that are intrinsically undesirable. Examples include “never events”, such as a foreign body left in during surgery or surgery on the wrong side of the body. If the measurement purpose is quality improvement, each individual event would trigger further analysis and investigation to avoid similar problems in the future.

Another option is to distinguish between generic and disease-specific indicators. Generic indicators measure aspects of care that are relevant to all patients. One example of a generic indicator is the proportion of patients who waited more than six hours in the emergency department. Disease-specific indicators are relevant only for patients with a particular diagnosis, such as the proportion of patients with lung cancer who are alive 30 days after surgery.

Yet other options relate to the different lenses of the framework presented in Chapter 2 . Indicators can be classified depending on the dimension of quality that they assess, i.e. effectiveness, patient safety and/or patient-centredness (the first lens); and with regard to the assessed function of healthcare, i.e. prevention, acute, chronic and/or palliative care (the second lens). Furthermore, it is possible to distinguish between patient-based indicators and event-based indicators. Patient-based indicators are indicators that are developed based on data that are linked across settings, allowing the identification of the pathway of care provided to individual patients. Event-based indicators are related to a specific event, for example, a hospital admission.

However, the most frequently used framework for distinguishing between different types of quality indicators is Donabedian’s classification of structure, process and outcome indicators (Donabedian, 1980 ). Donabedian’s triad builds the fourth lens of the framework presented in Chapter 2 . The idea is that the structures where health care is provided have an effect on the processes of care, which in turn will influence patient health outcomes. Table 3.2 provides some examples of structure, process and outcome indicators related to the different dimensions of quality.

Examples of structure, process and outcome quality indicators for different dimensions of quality.

In general, structural quality indicators are used to assess the setting of care, such as the adequacy of facilities and equipment, staffing ratios, qualifications of medical staff and administrative structures. Structural indicators related to effectiveness include the availability of staff with an appropriate skill mix, while the availability of safe medicines and the volume of surgeries performed are considered to be more related to patient safety. Structural indicators for patient-centredness can include the organizational implementation of a patients’ rights charter or the availability of patient information. Although institutional structures are certainly important for providing high-quality care, it is often difficult to establish a clear link between structures and clinical processes or outcomes, which reduces, to a certain extent, the relevance of structural measures.

Process indicators are used to assess whether actions indicating high-quality care are undertaken during service provision. Ideally, process indicators are built on reliable scientific evidence that compliance with these indicators is related to better outcomes of care. Sometimes process indicators are developed on the basis of clinical guidelines ( see also Chapter 9 ) or some other golden standard. For example, a process indicator of effective care for AMI patients may assess if patients are given aspirin on arrival. A process indicator of safety in surgery may assess if a safety checklist is used during surgery, and process indicators for patient-centredness may analyse patient-reported experience measures (PREMs). Process measures account for the majority of most quality measurement frameworks (Cheng et al., 2014 ; Fujita, Moles & Chen, 2018 ; NQF, 2019a ).

Finally, outcome indicators provide information about whether healthcare services help people stay alive and healthy. Outcome indicators are usually concrete and highly relevant to patients. For example, outcome indicators of effective ambulatory care include hospitalization rates for preventable conditions. Indicators of effective inpatient care for patients with acute myocardial infarction often include mortality rates within 30 days after admission, preferably calculated as a patient-based indicator (i.e. capturing deaths in any setting outside the hospital) and not as an event-based indicator (i.e. capturing death only within the hospital). Outcome indicators of patient safety may include complications of treatment, such as hospital acquired infections or foreign bodies left in during surgery. Outcome indicators of patient-centredness may assess patient satisfaction or patients’ willingness to recommend the hospital. Outcome indicators are increasingly used in quality measurement programmes, in particular in the USA, because they are of greater interest to patients and payers (Baker & Chassin, 2017 ).

3.5. Advantages and disadvantages of different types of indicators

Different types of indicators have their various strengths and weaknesses:

- Generic indicators have the advantage that they assess aspects of healthcare quality that are relevant to all patients. Therefore, generic indicators are potentially meaningful for a greater audience of patients, payers and policy-makers.

- Disease-specific indicators are better able to capture different aspects of healthcare quality that are relevant for improving patient care. In fact, most aspects of healthcare quality are disease-specific because effectiveness, safety and patient-centredness mean different things for different groups of diseases. For example, prescribing aspirin at discharge is an indicator of providing effective care for patients after acute myocardial infarction. However, if older patients are prescribed aspirin for extended periods of time without receiving gastro-protective medicines, this is an indicator of safety problems in primary care (NHS BSA, 2019 ).

Likewise, structure, process and outcome indicators each have their comparative strengths and weaknesses. These are summarized in Table 3.3 . The strength of structural measures is that they are easily available, reportable and verifiable because structures are stable and easy to observe. However, the main weakness is that the link between structures and clinical processes or outcomes is often indirect and dependent on the actions of healthcare providers.

Strengths and weaknesses of different types of indicators.

Process indicators are also measured relatively easily, and interpretation is often straightforward because there is often no need for risk-adjustment. In addition, poor performance on process indicators can be directly attributed to the actions of providers, thus giving clear indication for improvement, for example, by better adherence to clinical guidelines (Rubin, Pronovost & Diette, 2001 ). However, healthcare is complex and process indicators usually focus only on very specific procedures for a specific group of patients. Therefore, hundreds of indicators are needed to enable a comprehensive analysis of the quality of care provided by a professional or an institution. Relying only on a small set of process indicators carries the risk of distorting service provision towards a focus on measured areas of care while disregarding other (potentially more) important tasks that are harder to monitor.

Outcome indicators place the focus of quality assessments on the actual goals of service provision. Outcome indicators are often more meaningful to patients and policy-makers. The use of outcome indicators may also encourage innovations in service provision if these lead to better outcomes than following established processes of care. However, attributing health outcomes to the services provided by individual organizations or professionals is often difficult because outcomes are influenced by many factors outside the control of a provider (Lilford et al., 2004 ). In addition, outcomes may require a long time before they manifest themselves, which makes outcome measures more difficult to use for quality measurement (Donabedian, 1980 ). Furthermore, poor performance on outcome indicators does not necessarily provide direct indication for action as the outcomes may be related to a range of actions of different individuals who worked in a particular setting at a prior point in time.

3.6. Aggregating information in composite indicators

Given the complexity of healthcare provision and the wide range of relevant quality aspects, many quality measurement systems produce a large number of quality indicators. However, the availability of numerous different indicators may make it difficult for patients to select the best providers for their needs and for policy-makers to know whether overall quality of healthcare provision is improving. In addition, purchasers may struggle with identifying good-quality providers if they do not have a metric for aggregating conflicting results from different indicators. As a result, some users of quality information might base their decisions on only a few selected indicators that they understand, although these may not be the most important ones, and the information provided by many other relevant indicators will be lost (Goddard & Jacobs, 2009 ).

In response to these problems, many quality measurement initiatives have developed methods for combining different indicators into composite indicators or composite scores (Shwartz, Restuccia & Rosen, 2015 ). The use of composite indicators allows the aggregation of different aspects of quality into one measure to give a clearer picture of the overall quality of healthcare providers. The advantage is that the indicator summarizes information from a potentially wide range of individual indicators, thus providing a comprehensive assessment of quality. Composite indicators can serve many purposes: patients can select providers based on composite scores; hospital managers can use composite indicators to benchmark their hospitals against others, policy-makers can use composite indicators to assess progress over time, and researchers can use composite indicators for further analyses, for example, to identify factors associated with good quality of care. Table 3.4 summarizes some of the advantages and disadvantages of composite indicators.

Advantages and disadvantages of composite indicators.

The main disadvantages of composite indicators include that there are different (valid) options for aggregating individual indicators into composite indicators and that the methodological choices made during indicator construction will influence the measured performance. In addition, composite indicators may lead to simplistic conclusions and disguise serious failings in some dimensions. Furthermore, because of the influence of methodological choices on results, the selection of constituting indicators and weights could become the subject of political dispute. Finally, composite indicators do not allow the identification of specific problem areas and thus they need to be used in conjunction with individual quality indicators in order to enable quality improvement.

There are at least three important methodological choices that have to be made to construct a composite indicator. First, individual indicators have to be chosen to be combined in the composite indicator. Of course, the selection of indicators and the quality of chosen indicators will be decisive for the reliability of the overall composite indicator. Secondly, individual indicators have to be transformed into a common scale to enable aggregation. There are many methods available for this rescaling of the results, including ranking, normalizing (for example, using z-scores), calculating the proportion of the range of scores, and grouping scores into categories (for example, 5 stars) (Shwartz, Restuccia & Rosen, 2015 ). All of these methods have their comparative advantages and disadvantages and there is no consensus about which one should be used for the construction of composite indicators.

Thirdly, weights have to be attached to the individual indicators, which signal the relative importance of the different components of the composite indicator. Potentially, the ranking of providers can change dramatically depending on the weights given to individual indicators (Goddard & Jacobs, 2009 ). Again, several options exist. The most straightforward way is to use equal weights for every indicator but this is unlikely to reflect the relative importance of individual measures. Another option is to base the weights on expert judgement or preferences of the target audience. Further options include opportunity-based weighting, also called denominator-based weights because more weight is given to indicators for more prevalent conditions (for example, higher weights for diabetes-related indicators than for acromegaly-related indicators), and numerator-based weights which give more weight to indicators covering a larger number of events (for example, higher weight on medication interaction than on wrong-side surgery). Finally, yet another option is to use an all-or-none approach at the patient level, where a score of one is given only if all requirements for an individual patient have been met (for example, all five recommended pre-operative processes were performed).

Again, there is no clear guidance on how best to construct a composite indicator. However, what is important is that indicator construction is transparent and that methodological choices and rationales are clearly explained to facilitate understanding. Furthermore, different choices will provide different incentives for improvement and these need to be considered during composite construction.

3.7. Selection of indicators

A wide range of existing indicators is available that can form the basis for the development of new quality measurement initiatives. For example, the National Quality Forum (NQF) in the USA provides an online database with more than a thousand quality indicators that can be searched by type of indicator (structure, process, outcome), by clinical area (for example, dental, cancer or eye care), by target of measurement (for example, provider, payer, population), and by endorsement status (i.e. whether they meet the NQF’s measure evaluation criteria) (NQF, 2019a ). The OECD Health Care Quality Indicator Project provides a list of 55 quality indicators for cross-country analyses of the quality of primary care, acute care and mental care, as well as patient safety and patient experiences (OECD HCQI, 2016 ). The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has developed a broad set of indicators for hospitals, primary care, patient safety and patient experience, among others (ACSQHC, 2019 ).

The English Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) includes 77 indicators for evaluating the quality of primary care (NHS Employers, 2018 ), and these indicators have inspired several other countries to develop their own quality indicators for primary care. The NHS also publishes indicators for the assessment of medication safety (NHS BSA, 2019 ). In addition, several recent reviews have summarized available quality indicators for different areas of care, for example, palliative care (Pfaff & Markaki, 2017 ), mental health (Parameswaran, Spaeth-Rublee & Alan Pincus, 2015 ), primary care for patients with serious mental illnesses (Kronenberg et al., 2017 ), cardiovascular care (Campbell et al., 2008 ), and for responsible use of medicines (Fujita, Moles & Chen, 2018 ). Different chapters in this book will refer to indicators as part of specific quality strategies such as public reporting ( see Chapter 13 ).

In fact, there is a plethora of indicators that can potentially be used for measurement for the various purposes described previously ( see section above: Different purposes of quality measurement and users of quality information). However, because data collection and analysis may consume considerable resources, and because quality measurement may have unintended consequences, initiatives have to carefully select (or newly develop) indicators based on the identified quality problem, the interested stakeholders and the purpose of measurement (Evans et al., 2009 ).

Quality measurement that aims to monitor and/or address problems related to specific diseases, for example, cardiovascular or gastrointestinal diseases, or particular groups of patients, for example, geriatric patients or paediatric patients, will likely require disease-specific indicators. By contrast, quality measurement aiming to address problems related to the organization of care (for example, waiting times in emergency departments), to specific providers (for example, falls during inpatient stays), or professionals (for example, insufficiently qualified personnel) will likely require generic indicators. Quality problems related to the effectiveness of care are likely to require rate-based disease-specific indicators, while safety problems are more likely to be addressed through (often generic) sentinel event indicators. Problems with regard to patient-centredness will likely require indicators based on patient surveys and expressed as rates.

The interested stakeholders and the purpose of measurement should determine the desired level of detail and the focus of measurement on structures, processes or outcomes. This is illustrated in Table 3.5 , which summarizes the information needs of different stakeholders in relation to their different purposes. For example, governments responsible for assuring overall quality and accountability of healthcare service provision will require relatively few aggregated composite indicators, mostly of health outcomes, to monitor overall system level performance and to assure value for money. By contrast, provider organizations and professionals, which are mostly interested in quality improvement, are likely to demand a high number of disease-specific process indicators, which allows identification of areas for quality improvement.

Information needs of health system stakeholders with regard to quality of care.

Another issue that needs to be considered when choosing quality indicators is the question of finding the right balance between coverage and practicality. Relying on only a few indicators causes some aspects of care quality to be neglected and potentially to distract attention away from non-measured areas. It may also be necessary to have more than one indicator for one quality aspect, for example, mortality, readmissions and a PREM. However, maintaining too many indicators will be expensive and impractical to use. Finally, the quality of quality indicators should be a determining factor in selecting indicators for measurement.

3.8. Quality of quality indicators

There are numerous guidelines and criteria available for evaluating the quality of quality indicators. In 2006 the OECD Health Care Quality Indicators Project published a list of criteria for the selection of quality indicators (Kelley & Hurst, 2006 ). A relatively widely used tool for the evaluation of quality indicators has been developed at the University of Amsterdam, the Appraisal of Indicators through Research and Evaluation (AIRE) instrument (de Koning, Burgers & Klazinga, 2007 ). The NQF in the USA has published its measure evaluation criteria, which form the basis for evaluations of the eligibility of quality indicators for endorsement (NQF, 2019b ). In Germany yet another tool for the assessment of quality indicators – the QUALIFY instrument – was developed by the Federal Office for Quality Assurance (BQS) in 2007, and the Institute for Quality Assurance and Transparency in Health Care (IQTIG) defined a similar set of criteria in 2018 (IQTIG, 2018 ).

In general, the criteria defined by the different tools are quite similar but each tool adds certain aspects to the list. Box 3.1 summarizes the criteria defined by the various tools grouped along the dimensions of relevance, scientific soundness, feasibility and meaningfulness. The relevance of an indicator can be determined based on its effect on health or health expenditures, the importance that it has for the relevant stakeholders, the potential for improvement (for example, as determined by available evidence about practice variation), and the clarity of the purpose and the healthcare context for which the indicator was developed. The latter point is important because many of the following criteria are dependent on the specific purpose.

Criteria for indicators.

For example, the desired level for the criteria of validity, sensitivity and specificity will differ depending on whether the purpose is external quality assurance or internal quality improvement. Similarly, if the purpose is to assure a minimum level of quality across all providers, the appraisal concept has to focus on minimum acceptable requirements, while it will have to distinguish between good and very good performers if the aim is to reward high-quality providers through a pay for quality approach ( see Chapter 14 ).

Important aspects that need to be considered with regard to feasibility of measurement include whether previous experience exists with the use of the measure, whether the necessary information is available or can be collected in the required timeframe, whether the costs of measurement are acceptable, and whether the data will allow meaningful analyses for relevant subgroups of the population (for example, by socioeconomic status). Furthermore, the meaningfulness of the indicator is an important criterion, i.e. whether the indicator allows useful comparisons, whether the results are user-friendly for the target audience, and whether the distinction between high and low quality is meaningful for the target audience.

3.9. Data sources for measuring quality

Many different kinds of data are available that can potentially be used for quality measurement. The most often used data sources are administrative data, medical records of providers and data stored in different – often disease-specific – registers, such as cancer registers. In addition, surveys of patients or healthcare personnel can be useful to gain additional insights into particular dimensions of quality. Finally, other approaches, such as direct observation of a physician’s activities by a qualified colleague, are useful under specific conditions (for example, in a research context) but usually not possible for continuous measurement of quality.

There are many challenges with regard to the quality of the available data. These challenges can be categorized into four key aspects: (1) completeness, (2) comprehensiveness, (3) validity and (4) timeliness. Completeness means that the data properly include all patients with no missing cases. Comprehensiveness refers to whether the data contain all relevant variables needed for analysis, such as diagnosis codes, results of laboratory tests or procedures performed. Validity means that the data accurately reflect reality and are free of bias and errors. Finally, timeliness means that the data are available for use without considerable delay.

Data sources differ in their attributes and have different strengths and weaknesses, which are presented below and summarized in Table 3.6 . The availability of data for research and quality measurement purposes differs substantially between countries. Some countries have more restrictive data privacy protection legislation in place, and also the possibility of linking different databases using unique personal identifiers is not available in all countries (Oderkirk, 2013 ; Mainz, Hess & Johnsen, 2019 ). Healthcare providers may also use patient data only for internal quality improvement purposes and prohibit transfer of data to external bodies. Nevertheless, with the increasing diffusion of IT technology in the form of electronic health records, administrative databases and clinical registries, opportunities of data linkage are increasing, potentially creating new and better options for quality measurement.

Strengths and weaknesses of different data sources.

3.9.1. Administrative data

Administrative data are not primarily generated for quality or research purposes but by definition for administrative and management purposes (for example, billing data, routine documentation) and have the advantage of being readily available and easily accessible in electronic form. Healthcare providers, in particular hospitals, are usually mandated to maintain administrative records, which are used in many countries for quality measurement purposes. In addition, governments usually have registers of births and deaths that are potentially relevant for quality measurement but which are often not used by existing measurement systems.