Persuasive Writing In Three Steps: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

April 14, 2021 by Ryan Law in

Great writing persuades. It persuades the reader that your product is right for them, that your process achieves the outcome they desire, that your opinion supersedes all other opinions. But spend an hour clicking around the internet and you’ll quickly realise that most content is passive, presenting facts and ideas without context or structure. The reader must connect the dots and create a convincing argument from the raw material presented to them. They rarely do, and for good reason: It’s hard work. The onus of persuasion falls on the writer, not the reader. Persuasive communication is a timeless challenge with an ancient solution. Zeno of Elea cracked it in the 5th century B.C. Georg Hegel gave it a lick of paint in the 1800s. You can apply it to your writing in three simple steps: thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

Use Dialectic to Find Logical Bedrock

“ Dialectic ” is a complicated-sounding idea with a simple meaning: It’s a structured process for taking two seemingly contradictory viewpoints and, through reasoned discussion, reaching a satisfactory conclusion. Over centuries of use the term has been burdened with the baggage of philosophy and academia. But at its heart, dialectics reflects a process similar to every spirited conversation or debate humans have ever had:

- Person A presents an idea: “We should travel to the Eastern waterhole because it’s closest to camp.”

- Person B disagrees and shares a counterargument: “I saw wolf prints on the Eastern trail, so we should go to the Western waterhole instead.”

- Person A responds to the counterargument , either disproving it or modifying their own stance to accommodate the criticism: “I saw those same wolf prints, but our party is large enough that the wolves won’t risk an attack.”

- Person B responds in a similar vein: “Ordinarily that would be true, but half of our party had dysentery last week so we’re not at full strength.”

- Person A responds: “They got dysentery from drinking at the Western waterhole.”

This process continues until conversational bedrock is reached: an idea that both parties understand and agree to, helped by the fact they’ve both been a part of the process that shaped it.

Dialectic is intended to help draw closer to the “truth” of an argument, tempering any viewpoint by working through and resolving its flaws. This same process can also be used to persuade.

Create Inevitability with Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

The philosopher Georg Hegel is most famous for popularizing a type of dialectics that is particularly well-suited to writing: thesis, antithesis, synthesis (also known, unsurprisingly, as Hegelian Dialectic ).

- Thesis: Present the status quo, the viewpoint that is currently accepted and widely held.

- Antithesis: Articulate the problems with the thesis. (Hegel also called this phase “the negative.”)

- Synthesis: Share a new viewpoint (a modified thesis) that resolves the problems.

Hegel’s method focused less on the search for absolute truth and more on replacing old ideas with newer, more sophisticated versions . That, in a nutshell, is the same objective as much of content marketing (and particularly thought leadership content ): We’re persuading the reader that our product, processes, and ideas are better and more useful than the “old” way of doing things. Thesis, antithesis, synthesis (or TAS) is a persuasive writing structure because it:

- Reduces complex arguments into a simple three-act structure. Complicated, nuanced arguments are simplified into a clear, concise format that anyone can follow. This simplification reflects well on the author: It takes mastery of a topic to explain it in it the simplest terms.

- Presents a balanced argument by “steelmanning” the best objection. Strong, one-sided arguments can trigger reactance in the reader: They don’t want to feel duped. TAS gives voice to their doubts, addressing their best objection and “giv[ing] readers the chance to entertain the other side, making them feel as though they have come to an objective conclusion.”

- Creates a sense of inevitability. Like a story building to a satisfying conclusion, articles written with TAS take the reader on a structured, logical journey that culminates in precisely the viewpoint we wish to advocate for. Doubts are voiced, ideas challenged, and the conclusion reached feels more valid and concrete as a result.

There are two main ways to apply TAS to your writing: Use it beef up your introductions, or apply it to your article’s entire structure.

Writing Article Introductions with TAS

Take a moment to scroll back to the top of this article. If I’ve done my job correctly, you’ll notice a now familiar formula staring back at you: The first three paragraphs are built around Hegel’s thesis, antithesis, synthesis structure. Here’s what the introduction looked like during the outlining process . The first paragraph shares the thesis, the accepted idea that great writing should be persuasive:

Next up, the antithesis introduces a complicating idea, explaining why most content marketing isn’t all that persuasive:

Finally, the synthesis shares a new idea that serves to reconcile the two previous paragraphs: Content can be made persuasive by using the thesis, antithesis, synthesis framework. The meat of the article is then focused on the nitty-gritty of the synthesis.

Introductions are hard, but thesis, antithesis, synthesis offers a simple way to write consistently persuasive opening copy. In the space of three short paragraphs, the article’s key ideas are shared , the entire argument is summarised, and—hopefully—the reader is hooked.

Best of all, most articles—whether how-to’s, thought leadership content, or even list content—can benefit from Hegelian Dialectic , for the simple reason that every article introduction should be persuasive enough to encourage the reader to stick around.

Structuring Entire Articles with TAS

Harder, but most persuasive, is to use thesis, antithesis, synthesis to structure your entire article. This works best for thought leadership content. Here, your primary objective is to advocate for a new idea and disprove the old, tired way of thinking—exactly the use case Hegel intended for his dialectic. It’s less useful for content that explores and illustrates a process, because the primary objective is to show the reader how to do something (like this article—otherwise, I would have written the whole darn thing using the framework). Arjun Sethi’s article The Hive is the New Network is a great example.

The article’s primary purpose is to explain why the “old” model of social networks is outmoded and offer a newer, better framework. (It would be equally valid—but less punchy—to publish this with the title “ Why the Hive is the New Network.”) The thesis, antithesis, synthesis structure shapes the entire article:

- Thesis: Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram grew by creating networks “that brought existing real-world relationships online.”

- Antithesis: As these networks grow, the less useful they become, skewing towards bots, “celebrity, meme and business accounts.”

- Synthesis: To survive continued growth, these networks need to embrace a new structure and become hives.

With the argument established, the vast majority of the article is focused on synthesis. After all, it requires little elaboration to share the status quo in a particular situation, and it’s relatively easy to point out the problems with a given idea. The synthesis—the solution that needs to reconcile both thesis and antithesis—is the hardest part to tackle and requires the greatest word count. Throughout the article, Arjun is systematically addressing the “best objections” to his theory and demonstrating why the “Hive” is the best solution:

- Antithesis: Why now? Why didn’t Hives emerge in the first place?

- Thesis: We were limited by technology, but today, we have the necessary infrastructure: “We’re no longer limited to a broadcast radio model, where one signal is received by many nodes. ...We sync with each other instantaneously, and all the time.”

- Antithesis: If the Hive is so smart, why aren’t our brightest and best companies already embracing it?

- Thesis: They are, and autonomous cars are a perfect example: “Why are all these vastly different companies converging on the autonomous car? That’s because for these companies, it’s about platform and hive, not just about roads without drivers.”

It takes bravery to tackle objections head-on and an innate understanding of the subject matter to even identify objections in the first place, but the effort is worthwhile. The end result is a structured journey through the arguments for and against the “Hive,” with the reader eventually reaching the same conclusion as the author: that “Hives” are superior to traditional networks.

Destination: Persuasion

Persuasion isn’t about cajoling or coercing the reader. Statistics and anecdotes alone aren’t all that persuasive. Simply sharing a new idea and hoping that it will trigger an about-turn in the reader’s beliefs is wishful thinking. Instead, you should take the reader on a journey—the same journey you travelled to arrive at your newfound beliefs, whether it’s about the superiority of your product or the zeitgeist-changing trend that’s about to break. Hegelian Dialectic—thesis, antithesis, synthesis— is a structured process for doing precisely that. It contextualises your ideas and explains why they matter. It challenges the idea and strengthens it in the process. Using centuries-old processes, it nudges the 21st-century reader onto a well-worn path that takes them exactly where they need to go.

Ryan is the Content Director at Ahrefs and former CMO of Animalz.

Why ‘Vertical Volatility’ Is the Missing Link in Your Keyword Strategy

Get insight and analysis on the world's top SaaS brands, each and every Monday morning.

Success! Now check your email to confirm your subscription.

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

- Scholarly Community Encyclopedia

- Log in/Sign up

Video Upload Options

- MDPI and ACS Style

- Chicago Style

In philosophy, the triad of thesis, antithesis, synthesis (German: These, Antithese, Synthese; originally: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis) is a progression of three ideas or propositions. The first idea, the thesis, is a formal statement illustrating a point; it is followed by the second idea, the antithesis, that contradicts or negates the first; and lastly, the third idea, the synthesis, resolves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis. It is often used to explain the dialectical method of German philosopher Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, but Hegel never used the terms himself; instead his triad was concrete, abstract, absolute. The thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad actually originated with Johann Fichte.

1. History of the Idea

Thomas McFarland (2002), in his Prolegomena to Coleridge's Opus Maximum , [ 1 ] identifies Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) as the genesis of the thesis/antithesis dyad. Kant concretises his ideas into:

- Thesis: "The world has a beginning in time, and is limited with regard to space."

- Antithesis: "The world has no beginning and no limits in space, but is infinite, in respect to both time and space."

Inasmuch as conjectures like these can be said to be resolvable, Fichte's Grundlage der gesamten Wissenschaftslehre ( Foundations of the Science of Knowledge , 1794) resolved Kant's dyad by synthesis, posing the question thus: [ 1 ]

- No synthesis is possible without a preceding antithesis. As little as antithesis without synthesis, or synthesis without antithesis, is possible; just as little possible are both without thesis.

Fichte employed the triadic idea "thesis–antithesis–synthesis" as a formula for the explanation of change. [ 2 ] Fichte was the first to use the trilogy of words together, [ 3 ] in his Grundriss des Eigentümlichen der Wissenschaftslehre, in Rücksicht auf das theoretische Vermögen (1795, Outline of the Distinctive Character of the Wissenschaftslehre with respect to the Theoretical Faculty ): "Die jetzt aufgezeigte Handlung ist thetisch, antithetisch und synthetisch zugleich." ["The action here described is simultaneously thetic, antithetic, and synthetic." [ 4 ] ]

Still according to McFarland, Schelling then, in his Vom Ich als Prinzip der Philosophie (1795), arranged the terms schematically in pyramidal form.

According to Walter Kaufmann (1966), although the triad is often thought to form part of an analysis of historical and philosophical progress called the Hegelian dialectic, the assumption is erroneous: [ 5 ]

Whoever looks for the stereotype of the allegedly Hegelian dialectic in Hegel's Phenomenology will not find it. What one does find on looking at the table of contents is a very decided preference for triadic arrangements. ... But these many triads are not presented or deduced by Hegel as so many theses, antitheses, and syntheses. It is not by means of any dialectic of that sort that his thought moves up the ladder to absolute knowledge.

Gustav E. Mueller (1958) concurs that Hegel was not a proponent of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and clarifies what the concept of dialectic might have meant in Hegel's thought. [ 6 ]

"Dialectic" does not for Hegel mean "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis." Dialectic means that any "ism" – which has a polar opposite, or is a special viewpoint leaving "the rest" to itself – must be criticized by the logic of philosophical thought, whose problem is reality as such, the "World-itself".

According to Mueller, the attribution of this tripartite dialectic to Hegel is the result of "inept reading" and simplistic translations which do not take into account the genesis of Hegel's terms:

Hegel's greatness is as indisputable as his obscurity. The matter is due to his peculiar terminology and style; they are undoubtedly involved and complicated, and seem excessively abstract. These linguistic troubles, in turn, have given rise to legends which are like perverse and magic spectacles – once you wear them, the text simply vanishes. Theodor Haering's monumental and standard work has for the first time cleared up the linguistic problem. By carefully analyzing every sentence from his early writings, which were published only in this century, he has shown how Hegel's terminology evolved – though it was complete when he began to publish. Hegel's contemporaries were immediately baffled, because what was clear to him was not clear to his readers, who were not initiated into the genesis of his terms. An example of how a legend can grow on inept reading is this: Translate "Begriff" by "concept," "Vernunft" by "reason" and "Wissenschaft" by "science" – and they are all good dictionary translations – and you have transformed the great critic of rationalism and irrationalism into a ridiculous champion of an absurd pan-logistic rationalism and scientism. The most vexing and devastating Hegel legend is that everything is thought in "thesis, antithesis, and synthesis." [ 7 ]

Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) adopted and extended the triad, especially in Marx's The Poverty of Philosophy (1847). Here, in Chapter 2, Marx is obsessed by the word "thesis"; [ 8 ] it forms an important part of the basis for the Marxist theory of history. [ 9 ]

2. Writing Pedagogy

In modern times, the dialectic of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis has been implemented across the world as a strategy for organizing expositional writing. For example, this technique is taught as a basic organizing principle in French schools: [ 10 ]

The French learn to value and practice eloquence from a young age. Almost from day one, students are taught to produce plans for their compositions, and are graded on them. The structures change with fashions. Youngsters were once taught to express a progression of ideas. Now they follow a dialectic model of thesis-antithesis-synthesis. If you listen carefully to the French arguing about any topic they all follow this model closely: they present an idea, explain possible objections to it, and then sum up their conclusions. ... This analytical mode of reasoning is integrated into the entire school corpus.

Thesis, Antithesis, and Synthesis has also been used as a basic scheme to organize writing in the English language. For example, the website WikiPreMed.com advocates the use of this scheme in writing timed essays for the MCAT standardized test: [ 11 ]

For the purposes of writing MCAT essays, the dialectic describes the progression of ideas in a critical thought process that is the force driving your argument. A good dialectical progression propels your arguments in a way that is satisfying to the reader. The thesis is an intellectual proposition. The antithesis is a critical perspective on the thesis. The synthesis solves the conflict between the thesis and antithesis by reconciling their common truths, and forming a new proposition.

- Samuel Taylor Coleridge: Opus Maximum. Princeton University Press, 2002, p. 89.

- Harry Ritter, Dictionary of Concepts in History. Greenwood Publishing Group (1986), p.114

- Williams, Robert R. (1992). Recognition: Fichte and Hegel on the Other. SUNY Press. p. 46, note 37.

- Fichte, Johann Gottlieb; Breazeale, Daniel (1993). Fichte: Early Philosophical Writings. Cornell University Press. p. 249.

- Walter Kaufmann (1966). "§ 37". Hegel: A Reinterpretation. Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-268-01068-3. OCLC 3168016. https://archive.org/details/hegelreinterpret00kauf.

- Mueller, Gustav (1958). "The Hegel Legend of "Thesis-Antithesis-Synthesis"". Journal of the History of Ideas 19 (4): 411–414. doi:10.2307/2708045. https://dx.doi.org/10.2307%2F2708045

- Mueller 1958, p. 411.

- marxists.org: Chapter 2 of "The Poverty of Philosophy", by Karl Marx https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1847/poverty-philosophy/ch02.htm

- Shrimp, Kaleb (2009). "The Validity of Karl Marx's Theory of Historical Materialism". Major Themes in Economics 11 (1): 35–56. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/mtie/vol11/iss1/5/. Retrieved 13 September 2018.

- Nadeau, Jean-Benoit; Barlow, Julie (2003). Sixty Million Frenchmen Can't Be Wrong: Why We Love France But Not The French. Sourcebooks, Inc.. p. 62. https://archive.org/details/sixtymillionfren00nade_041.

- "The MCAT writing assignment.". Wisebridge Learning Systems, LLC. http://www.wikipremed.com/mcat_essay.php. Retrieved 1 November 2015.

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Advisory Board

Understanding Hegel’s Dialectical Method: Thesis, Antithesis, Synthesis

Imagine a world where every idea, belief, or concept you hold is continually challenged by its opposite. This dynamic tension and resolution lead to progress and change. Sounds intriguing, right? This is the essence of Hegel’s dialectical method, a philosophical approach that has significantly shaped Western thought. Today, we’ll unravel this fascinating method and explore how it can offer a deeper understanding of both ideas and history.

Table of Contents

- What is Hegel’s dialectical method?

- The origins: Inspiration from Socrates

- Applying the dialectical method to ideas and history

- Evolution of ideas

- Historical development

- Examples in contemporary context

- Technology and society

- Environmental sustainability

- The significance of Hegel’s dialectical method

- Criticisms and limitations

What is Hegel’s dialectical method? 🔗

Hegel’s dialectical method, inspired by Socratic dialogues, is a framework for understanding the evolution of ideas through a three-step process: thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. Here’s a closer look at each component:

- Thesis: This is the initial idea or proposition. It represents a starting point or an established belief.

- Antithesis: As the thesis exists, it naturally gives rise to its opposite, the antithesis. This opposing force challenges the thesis, creating conflict or contradiction.

- Synthesis: The conflict between the thesis and antithesis is resolved through synthesis, a higher level of understanding that integrates elements of both. This synthesis then becomes the new thesis, and the process begins anew.

This continuous cycle of contradiction and resolution drives progress and change, according to Hegel.

The origins: Inspiration from Socrates 🔗

Hegel’s dialectical method owes much to the Socratic method of dialogue. Socrates, the classical Greek philosopher, engaged in conversations where he would question and challenge participants to refine their ideas. This process of questioning and contradiction is a precursor to Hegel’s more structured dialectical method.

Applying the dialectical method to ideas and history 🔗

Hegel believed that the dialectical method could explain not only the development of ideas but also the unfolding of history. Let’s explore some of the key applications of this method:

Evolution of ideas 🔗

Hegel applied the dialectical method to understand the progression of human thought. Here are some examples:

- From family to state: Hegel viewed the family as the thesis, representing unity and togetherness. As individuals pursue their interests, the family structure gives rise to civil society (antithesis), characterized by individualism and competition. The resolution of this conflict is the state (synthesis), which harmonizes personal interests with collective well-being.

- From despotism to constitutional monarchy: In political thought, Hegel saw despotism (thesis) as an initial form of government with absolute power. The desire for freedom and democracy (antithesis) challenged this, leading to the synthesis of a constitutional monarchy, which balances authority with individual rights.

Historical development 🔗

Hegel’s dialectical method also provides a lens to view historical progress. He argued that history unfolds through a series of dialectical movements, where each age or epoch contains contradictions that drive humanity toward greater freedom and self-awareness. For example:

- Ancient empires: The centralized power of ancient empires (thesis) eventually faced opposition from the rise of individual liberties and democratic principles (antithesis).

- Modern state: The synthesis of these opposing forces is the modern state, which aims to balance centralized authority with individual rights and freedoms.

Examples in contemporary context 🔗

Hegel’s dialectical method isn’t just confined to historical and philosophical discussions; it can also be seen in contemporary contexts:

Technology and society 🔗

The rapid advancement of technology (thesis) has transformed our lives but also created challenges like privacy concerns and job displacement (antithesis). The ongoing synthesis involves finding ways to harness technology for social good while addressing its drawbacks.

Environmental sustainability 🔗

Industrial growth and economic development (thesis) have led to environmental degradation (antithesis). The synthesis lies in sustainable development practices that aim to balance economic progress with environmental preservation.

The significance of Hegel’s dialectical method 🔗

Hegel’s dialectical method offers several valuable insights:

- Understanding complexity: It helps us appreciate the complexity of ideas and historical events by recognizing the interplay of opposing forces.

- Encouraging critical thinking: The method encourages us to question established beliefs and consider alternative perspectives.

- Promoting progress: By highlighting the importance of resolving contradictions, it fosters a mindset of continuous improvement and innovation.

Criticisms and limitations 🔗

While Hegel’s dialectical method has been influential, it is not without its critics:

- Determinism: Some argue that Hegel’s view of history as a predetermined process undermines human agency and the role of chance.

- Abstractness: Critics also point out that the method can be highly abstract and difficult to apply to concrete situations.

- Eurocentrism: Hegel’s historical analysis has been criticized for its Eurocentric bias, overlooking non-Western perspectives and contributions.

Conclusion 🔗

Hegel’s dialectical method, with its dynamic interplay of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, provides a powerful framework for understanding the evolution of ideas and history. By recognizing the role of contradictions and their resolution, we can gain deeper insights into the complexities of our world and foster a mindset of continuous progress. Whether applied to philosophy, politics, or contemporary issues, Hegel’s method remains a valuable tool for critical thinking and innovation.

What do you think? How can we apply Hegel’s dialectical method to address current global challenges? Can you identify examples of thesis-antithesis-synthesis in your own life or society?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 0 / 5. Vote count: 0

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Western Political Thought (Plato to Marx)

1 Significance of Western Political Thought

- What is Political Thought?

- Distinction between Political Thought, Political Theory and Political Philosophy

- Relationship between Political Thought and Political Science

- Framework of Political Thought

- Western Political Thought, Political Institutions and Political Procedures

- Western Political Thought, Political Idealism and Political Realism

- Characteristic Features of the Great Works of Western Political Thought

- Relevance of Western Political Thought

- The Man and His Times

- His Methodology

- Socratic Base

- Theory of Ideas

- Theory of Justice

- Scheme of Education

- Community of Wives and Property

- Ideal State: The Ruling Class/Philosophic Ruler

- Plato’s Adversaries

- Plato’s Place in Western Political Theory

3 Aristotle

- Introduction

- Introducing Aristotle

- Philosophical Foundations of Aristotle’s Political Theory

- Plato and Aristotle

- Politics and Ethics

- Property, Family and Slavery

- Theory of Revolution

- Theory of State

- Evaluation of Aristotle’s Political Theory

4 St. Augustine & St. Thomas Aquinas

- Life and Work

- Civitas Dei Versus Civites Terrena

- Justice and the State

- State, Property, War and Slavery

- Augustine’s Influence

- St. Thomas Aquinas and the Grand Synthesis

- Law and the State

- Church and the State

5 Niccolo Machiavelli

- Machiavelli: A Child of His Time

- Methods of Machiavelli’s Study

- Machiavelli’s Political Thought

- Concept of Universal Egoism

- The “Prince”

- Machiavelli’s Classification of Forms of Government

- The Doctrine of Aggrandisement

6 Thomas Hobbes

- Life and Times

- The State of Nature and Natural Rights

- Laws of Nature and the Covenant

- The Covenant and the Creation of the Sovereign

- Rights and Duties of the Sovereign

- The Church and the State

- Civil Law and Natural Law

7 John Locke

- Life and Works

- Some Philosophical Problems

- Social Contract and Civil Society

- Consent, Resistance and Toleration

- The Lockean Legacy

8 Jean Jacques Rousseau

- Revolt against Reason

- Critique of Civil Society

- Social Contract

- Theory of General Will

- General Will as the Sovereign

- Critical Appreciation

9 Edmund Burke

- Restraining Royal Authority

- East India Company

- American Colonies

- Criticism of the French Revolution

- Critique of Natural Rights and Social Contract

- Limits of Reason

- Citizenship and Democracy

- Religion and Toleration

- Criticisms of Burke

10 Immanuel Kant

- Representative of the Enlightenment

- Kant’s “Copernican Revolution in Metaphysics”

- Transcendental-Idealist View of Human Reason

- Formulations of the Categorical Imperative

- The Universal Law of Right (Recht) or Justice

- Property, Social Contract, and the State

- Perpetual Peace

- Concluding Comments

11 Jeremy Bentham

- Utilitarian Principles

- Bentham’s Political Philosophy

- The Panopticon

12 Alexis de Tocqueville

- On Democracy, Revolution and the Modern State

- Women and Family

13 J.S. Mill

- Equal Rights for Women

- The Importance of Individual Liberty

- Representative Government

- Beyond Utilitarianism

14 George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel

- Spiritual Ancestry

- Dialectical Method

- Philosophy of History

- Theory of Freedom of the Individual

15 Karl Marx

- Theory of Alienation

- Theory of Historical Materialism

- Theory of Class War

- Theory of Surplus Value

- Dictatorship of the Proletariat

- Vision of a Communist Society

Share on Mastodon

- Organizations

- Planning & Activities

- Product & Services

- Structure & Systems

- Career & Education

- Entertainment

- Fashion & Beauty

- Political Institutions

- SmartPhones

- Protocols & Formats

- Communication

- Web Applications

- Household Equipments

- Career and Certifications

- Diet & Fitness

- Mathematics & Statistics

- Processed Foods

- Vegetables & Fruits

Difference Between Thesis and Antithesis

• Categorized under Miscellaneous | Difference Between Thesis and Antithesis

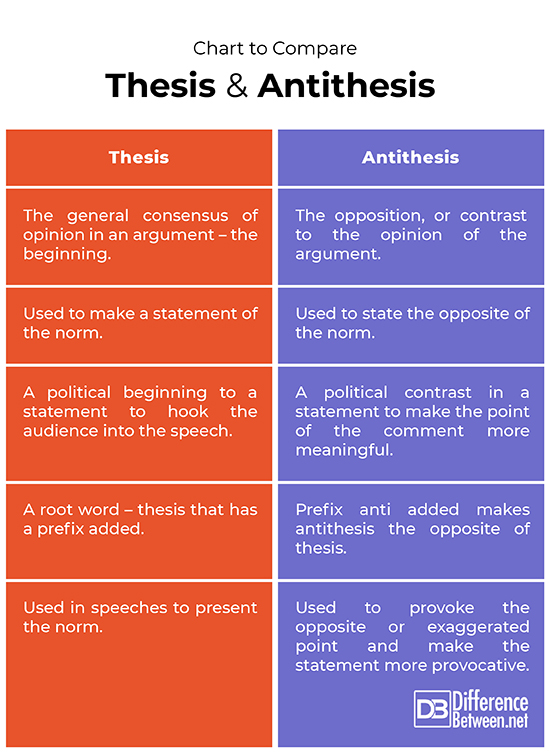

Thesis and antithesis are literary techniques used to make a point during a debate or a lecture or discourse about a topic. The thesis is the theory or the definition of the point under discussion. Antithesis is the exact opposite of the point made in the thesis. Anti is a prefix meaning against. The antithesis therefore goes against the thesis to create an opposition effect. The antithesis creates a clash of ideas or opinions and is a rhetorical device used to sway the opinions of the reader. The two opposite statements highlight a point in literature, politics and other forums of debate. Hearing the two sides of an argument has to have more impact on the reader or listener. The two opposing ideas make the writer’s point more definite and obvious.

Definition of Thesis

The thesis is the beginning of the study or debate. It is the introduction to the topic. The thesis is the normal way of looking at the subject matter. The thesis is the accepted way of thinking or viewing an issue to be discussed or written about. It is often the theory that is presented by philosophers and usually believed by the majority. A thesis can be used in a written document or as a speech. The thesis study looks at the positive side of the topic to be presented or discussed. The subject matter is usually what readers consider normal. In a political context it may be what is seen as the status quo. Not necessarily the right situation for the times politically, but what has been the norm, and what has been established before change must take place.

Definition of Antithesis

The antithesis is the opposite or opposition to the thesis. Anti being the prefix, and when it is added to thesis, spells antithesis. Anti changes the meaning of the word thesis. Opposition or an opposing statement or word, is the role that the antithesis plays. The antithesis helps to bring out the reason behind a debate or an emotive statement. Looking at the opposing theme and comparing the thesis and the antithesis highlights the mental picture through the anti aspect of the word antithesis. For example, when Neil Armstrong told the world he had made one small step for man and a giant leap for mankind he used the normal step he took as the thesis, and used the antithesis as a giant leap to create the picture of how great this step was for mankind. This created a memorable image, and shows the enormity of the first man walking on the moon. Antithesis is a form of rhetoric and a useful way of persuading people and igniting emotional reactions. Antithesis has been used by writers and politicians to stir emotions and bring home an important point.

What is the connection between Thesis, Antithesis and synthesis?

Thesis, together with antithesis results in a synthesis, according to philosopher Hegel. Hegel’s dialectics is a philosophical method involving a contradictory series of events between opposing sides. He describes the thesis as being the starting point, the antithesis is the reaction and the synthesis is the outcome from the reaction. Karl Marx used this philosophy to explain how communism came about. According to Marx’s theory:

The thesis was capitalism, the way Russia was run at the time.

The antithesis was the Proletariat, the industrial workers and labor force, at that time. The Proletariat decided to revolt against the capitalists, because they were being exploited. This reaction is the antithesis, or the opposition.

The synthesis results from these two groups opposing one another and there is an outcome, a synthesis. The outcome is a new order of things and new relationships. The new order was Communism. I t was a direct result of the antithesis or political opposition. The connection is therefore between the perceived ‘normal’ or starting point against the opposition, the antithesis, to create a new order of doing things.

How is Thesis and Antithesis used in literary circles?

Dramatic effect and contrasts of character are created through an antithesis. The writer uses the normal character matched with the completely opposite character to create an understanding or the different personalities or the different environment. Snow White and the wicked queen, who is the stepmother, are a shining example of antithesis. Hamlet’’s soliloquy, to be or not to be, sums up his dilemma at the time and creates a confusion of thought. Charles Dickens uses this rhetorical technique in a Tale of Two Cities as he describes ‘It was the best of times and the worst of times,’ when chapter one begins. The reader is immediately drawn into the story and the upsetting times of the French Revolution that is the scene for the book.

How are Thesis and Antithesis used in the political arena?

Well known politicians have used thesis and antithesis in their propaganda and speeches to rouse their followers. The well known Gettysburg address, given by Abraham Lincoln, used the antithesis of little and long at Gettysburg at the dedication to national heroism. Lincoln said:

“The world will little note, nor long remember, what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here.” This speech has gone down in history as one of the most important speeches and it has definitely been remembered.

Antithesis in a speech helps to advertise sentiments and rally crowds together due to its emotional power. Martin Luther King used antithesis to sway a crowd by saying unless people chose to live together as brothers they would surely perish as fools.

How does Thesis and Antithesis form part of a debate?

Formal debates make good use of the opposition concept brought about by the use of antithesis. The debate will start with the presentation of the thesis, followed by the antithesis and summed up in the synthesis. For example, a debate about eating meat could open with the points for eating meat. The next section of the debate argues for not eating meat and finally the points for and against could sum up eating meat, but as small portions of a persons dietary needs. The conflict of the argument comes between the thesis and the antithesis. The summary for the listeners to take away is the synthesis of the points made in the debate.

What makes Antithesis a rhetorical device?

The antithesis conjures up a more emotive response because of the opposition factor. Adding in the opposite or exaggerated form of a word in a statement makes more impact for the listener. In the event of a man walking on the moon, for example, this was not just a small event happening when a rocket went to the moon. No, this was a gigantic expedition to another planet. Whether it was intentional or not this statement has stood the test of time. It has become one of the most well known quotes highlighting a particular event. The clever use of the antithesis of a giant leap as part of the statement has made these words stand out in asthey marked this occasion. They bring the impact of these steps to the world as a great vision and achievement for mankind.

Chart to compare Thesis and Antithesis

Summary of Thesis and Antithesis:

- Thesis and antithesis are literary devices that highlight themes or emotional rhetorical situations.

- Well known events, using thesis and antithesis, show how this form of rhetoric creates an emotional response from readers or audiences. Neil Armstrong’s comment upon landing and walking on the moon for the first time in history is a shining example.

- The use of thesis and antithesis in literature enable the author to give more emphasis to an event or a theme in a story or play.

- Karl Marx used the thesis, antithesis and conclusion of a synthesis, to explain the evolution of communism.

- Using this format in debate helps to understand how two opposing ideals, around one debatable topic, can help the speakers provide their arguments. The debate is then wrapped up in a synthesis of ideas and the conclusion of the debate leading to a consensus of opinion.

- When well known politicians make a statement using thesis and antithesis, the statement is more powerful. These rhetorical statements become part of our history and become famous for the impact they made using just a few words to express a life changing situation.

- Recent Posts

- Difference Between Lagoon and Bay - October 20, 2021

- Difference Between Futurism and Preterism - August 12, 2021

- Difference Between Dichotomy and Paradox - August 7, 2021

Sharing is caring!

- Pinterest 3

Search DifferenceBetween.net :

- Difference Between Antithesis and Oxymoron

- Difference Between Thesis and Dissertation

- Difference Between Analysis and Synthesis

- Difference Between Full Moon and New Moon

- Difference Between Lunar Eclipse And New Moon

Cite APA 7 Wither, C. (2020, November 23). Difference Between Thesis and Antithesis. Difference Between Similar Terms and Objects. https://www.differencebetween.net/miscellaneous/difference-between-thesis-and-antithesis/. MLA 8 Wither, Christina. "Difference Between Thesis and Antithesis." Difference Between Similar Terms and Objects, 23 November, 2020, https://www.differencebetween.net/miscellaneous/difference-between-thesis-and-antithesis/.

Leave a Response

Name ( required )

Email ( required )

Please note: comment moderation is enabled and may delay your comment. There is no need to resubmit your comment.

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

References :

Advertisments, more in 'miscellaneous'.

- Difference Between Caucus and Primary

- Difference Between an Arbitrator and a Mediator

- Difference Between Cellulite and Stretch Marks

- Difference Between Taliban and Al Qaeda

- Difference Between Kung Fu and Karate

Top Difference Betweens

Get new comparisons in your inbox:, most emailed comparisons, editor's picks.

- Difference Between MAC and IP Address

- Difference Between Platinum and White Gold

- Difference Between Civil and Criminal Law

- Difference Between GRE and GMAT

- Difference Between Immigrants and Refugees

- Difference Between DNS and DHCP

- Difference Between Computer Engineering and Computer Science

- Difference Between Men and Women

- Difference Between Book value and Market value

- Difference Between Red and White wine

- Difference Between Depreciation and Amortization

- Difference Between Bank and Credit Union

- Difference Between White Eggs and Brown Eggs

What Is the Difference between Thesis and Antithesis?

Thesis and antithesis can be distinguished because they tend to involve completely opposed or conflicting ideas. They are used in many different settings, such as in literature and philosophical discourse. In some cases, they are used to make a point about an idea in a single comment or phrase, while in others, the two are sustained throughout an entire work, as when two characters are shown to have completely opposed characteristics over the course of a story. In philosophy, they are often combined into a synthesis that provides a new way of looking at the world.

Opposition is the defining feature that distinguishes thesis from antithesis in any given work. The two are commonly used in literature to demonstrate the opposition between two different ideas, actions, or characters. When Neil Armstrong first set foot on the moon, for instance, he described the action as “one small step for (a) man; one giant leap for mankind.” This use demonstrates the opposition inherent in the fact that, while Armstrong’s physical action was only a single step by a single man, it represented a tremendous leap forward and a momentous occasion for celebration on the part of mankind as a whole.

Writers may use thesis and antithesis in many different ways and for a variety of different reasons. In some cases, the techniques are used to demonstrate that two ideas, actions, or objects that appear unrelated are, in fact, inherently opposed to each other. In other cases, it may be used to point out contradictions in ideas that appear, upon casual examination, to agree with each other. In literature, the two are often embodied in characters. Two characters, such as a main character and a main villain or a character and his foil, are shown to embody ideas and to possess traits that are opposed at a fundamental level.

Thesis and antithesis also are often used in philosophical discussions in order to reach new conclusions about accepted ways of thinking. First, the thesis or accepted way of thinking or acting, is expressed. Next, an antithesis is proposed that demonstrates conflicts or problems with the original thesis. The third step is referred to as synthesis. The thesis and the problems and objections are combined in order to form a new worldview that more effectively or logically suggests a new manner of thought or action.

Literature Review Survival Library Guide: Thesis, antithesis and synthesis

- What is a literature review?

- Thesis, antithesis and synthesis

- 1. Choose your topic

- 2. Collect relevant material

- 3. Read/Skim articles

- 4. Group articles by themes

- 5. Use citation databases

- 6. Find agreement & disagreement

- Review Articles - A new option on Google Scholar

- How To Follow References

- Newspaper archives

- Aditi's Humanities Referencing Style Guide

- Referencing and RefWorks

- New-version RefWorks Demo

- Tracking Your Academic Footprint This link opens in a new window

- Finding Seminal Authors and Mapping the Shape of the Literature

- Types of Literature Review, including "Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide"

- Research Data Management

- Tamzyn Suleiman's guide to Systematic Reviews

- Danielle Abrahamse's Search String Design and Search Template

Thesis, antithesis, synthesis

The classic pattern of academic arguments is:

Thesis, antithesis, synthesis.

An Idea (Thesis) is proposed, an opposing Idea (Antithesis) is proposed, and a revised Idea incorporating (Synthesis) the opposing Idea is arrived at. This revised idea sometimes sparks another opposing idea, another synthesis, and so on…

If you can show this pattern at work in your literature review, and, above all, if you can suggest a new synthesis of two opposing views, or demolish one of the opposing views, then you are almost certainly on the right track.

Next topic: Step 1: Choose your topic

- << Previous: What is a literature review?

- Next: 1. Choose your topic >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lib.uct.ac.za/litreviewsurvival

Understanding Dialectical Method: An Introduction and Survey

The dialectical method is one of the most profound and transformative approaches in philosophy. Used to explore the nature of truth, ideas, and reality, it has shaped the thinking of some of the greatest minds in history. But what exactly is this method? How did it evolve, and why does it remain so significant in both philosophical inquiry and modern thought? In this blog, we’ll dive into the origins of the dialectical method, tracing its evolution from the ancient Greeks to its speculative applications in the work of philosophers like Hegel. By understanding this method, we’ll gain insight into how philosophers have used it to explore complex concepts, challenge assumptions, and evolve their understanding of the world.

Table of Contents

- What is the dialectical method?

- Historical roots of the dialectical method

- Plato’s contribution

- The evolution of dialectics in classical philosophy

- Aristotle’s logical dialectic

- Dialectics and modern philosophy

- Kant’s dialectic: The critique of reason

- Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel: Dialectic as the unfolding of reality

- Dialectical method across philosophical frameworks

- Dialectics in Marxism

- Dialectics in contemporary philosophy

What is the dialectical method? 🔗

The dialectical method is a way of thinking that involves examining and reconciling contradictions within ideas or concepts. It’s not just about identifying contradictions; it’s about understanding how these contradictions can lead to a deeper, more complex understanding of reality. In essence, dialectics is a process of evolution through conflict—an ongoing back-and-forth between opposing forces or ideas that ultimately leads to resolution and growth. In philosophy, this method has been used to explore everything from the nature of truth to the understanding of history, society, and even the cosmos itself.

Historical roots of the dialectical method 🔗

The roots of dialectical thinking can be traced back to ancient Greece, where early philosophers first grappled with the idea of how knowledge progresses and how reality can be understood. The most notable early figure to use dialectics was Socrates, who used a method known as the Socratic method. This method involved engaging in dialogue with others, asking questions that would help reveal contradictions in their beliefs, and guiding them toward a clearer, more precise understanding. While Socrates didn’t formalize the dialectical method as we know it today, his approach laid the groundwork for later developments.

Plato’s contribution 🔗

Plato, Socrates’ student, expanded on his teacher’s method of dialectical questioning in his dialogues. However, Plato’s dialectical method was far more formalized and aimed at uncovering abstract, universal truths. In works like “The Republic,” Plato used dialectic as a method to explore the nature of justice, virtue, and the ideal state. Plato’s dialectic was less about resolving contradictions and more about uncovering the forms—eternal, unchanging truths that lay behind the material world. For Plato, the dialectical process was a way to move from the physical world of appearances to the world of ideas, where true knowledge could be found.

The evolution of dialectics in classical philosophy 🔗

After Plato, dialectical thinking underwent a significant transformation, particularly in the hands of Aristotle. Aristotle’s contribution was to make dialectic a tool for logical argumentation and examination of opposing views. He developed formal logic as a way of identifying contradictions in arguments and resolving them. Aristotle’s dialectic was more concerned with how language and logic could be used to explore different perspectives, rather than revealing universal truths about the nature of reality. This shift represented a move away from abstract idealism toward a more empirical, logical approach to understanding the world.

Aristotle’s logical dialectic 🔗

Aristotle formalized dialectical reasoning in his work “Topics,” where he introduced a system of syllogistic logic. The dialectic in Aristotle’s system was about identifying opposing arguments and testing them through logical reasoning. In this sense, dialectics became more about the methodical evaluation of arguments to determine their validity, rather than discovering eternal forms. Aristotle’s approach laid the foundation for the kind of philosophical analysis that would be crucial in later philosophical traditions, particularly during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment.

Dialectics and modern philosophy 🔗

The dialectical method saw a significant resurgence in modern philosophy, particularly with the rise of German Idealism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Philosophers like Kant, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel applied dialectical reasoning in radically new ways. Instead of seeing dialectic as a way to analyze logical contradictions, they used it to understand the development of ideas, history, and the unfolding of reality itself.

Kant’s dialectic: The critique of reason 🔗

Immanuel Kant’s work in the 18th century represented a turning point in philosophy. Kant argued that while we can never know things as they are in themselves, we can still make sense of our experience of the world through the categories of our mind. In his “Critique of Pure Reason,” Kant used dialectical reasoning to explore the limits of human knowledge. His idea was that contradictions arise when we try to apply our categories (such as space, time, and causality) to concepts that lie beyond human experience. For Kant, dialectics was not just a way to resolve logical contradictions but a method of investigating the limits of human understanding itself.

Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel: Dialectic as the unfolding of reality 🔗

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel took dialectics in an even more speculative direction. For these philosophers, dialectical thinking was not just a method for examining contradictions in individual concepts or arguments; it was a way of understanding the entire process of reality’s development. In this view, reality itself is in a constant state of becoming, and dialectics serves as the engine of this process.

Fichte’s subjective idealism

Fichte was one of the first philosophers to fully embrace dialectics as a way of understanding how the self (the “I”) comes to understand the world. He argued that the “I” posits itself and creates the world through its own activity. For Fichte, dialectics was a way of understanding how the self and the world are intertwined in a process of mutual development. The “I” is constantly in tension with the world, and this tension drives the dialectical unfolding of reality.

Schelling’s nature and the Absolute

Schelling, a contemporary of Fichte, expanded dialectical thinking to include the natural world. He argued that nature itself is dialectical, evolving through a process of self-development. For Schelling, the dialectic revealed the unity of nature, mind, and spirit in the Absolute—a total, all-encompassing reality that transcends the distinction between subject and object.

Hegel’s dialectical idealism

Hegel is perhaps the most famous philosopher associated with the dialectical method. His dialectic was more systematic and complex than any before him. Hegel’s most famous formulation of dialectics is the triadic structure of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. According to Hegel, history, ideas, and reality itself unfold in a dialectical process. Each stage of development (thesis) creates its opposite (antithesis), and the tension between these opposites leads to a higher, more comprehensive synthesis. This process continues indefinitely, with each new synthesis becoming the starting point for a new dialectical progression. For Hegel, dialectics was the way in which spirit (or mind) comes to know itself through history, ultimately culminating in absolute knowing.

Dialectical method across philosophical frameworks 🔗

As we’ve seen, the dialectical method has evolved significantly throughout history, but its central principles—engaging contradictions, resolving oppositions, and understanding the development of ideas and reality—have remained consistent. The method’s adaptability across various philosophical frameworks is part of what has allowed it to endure as a powerful tool for intellectual inquiry.

Dialectics in Marxism 🔗

The dialectical method also played a crucial role in the development of Marxist thought. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels adapted Hegel’s dialectics to develop a materialist theory of history. Marx argued that history unfolds through a dialectical process driven by class struggles. The contradictions between the proletariat (working class) and the bourgeoisie (capitalist class) lead to revolutionary change and the eventual establishment of a classless society. Marx’s materialist dialectic emphasized the role of material conditions in shaping ideas and society, offering a stark contrast to the idealist dialectic of Hegel.

Dialectics in contemporary philosophy 🔗

In contemporary philosophy, the dialectical method continues to be relevant. It is used in fields such as political theory, cultural studies, and postmodern philosophy to examine contradictions within social structures, ideologies, and power dynamics. Philosophers like Theodor Adorno and Herbert Marcuse, key figures of the Frankfurt School, further developed dialectical thought by combining it with critical theory to analyze the relationship between society and individual freedom.

Conclusion 🔗

The dialectical method has come a long way since its beginnings in ancient Greece. From Socrates’ questioning to Hegel’s grand system of history, it has evolved into a complex and multifaceted tool for understanding the contradictions that shape our ideas, society, and reality. Whether in ancient debates about justice or modern critiques of capitalism, dialectics remains a powerful method for exploring the complexities of thought and the world. As you reflect on the dialectical method, think about how you encounter contradictions in your own thinking—how do opposing ideas or forces shape your understanding of the world? What insights might emerge from reconciling these contradictions?

What do you think? How do you see the dialectical method applying to the world today? Can you identify contradictions in contemporary debates that might benefit from dialectical analysis?

How useful was this post?

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating / 5. Vote count:

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.

We are sorry that this post was not useful for you!

Let us improve this post!

Tell us how we can improve this post?

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Research Methodology

1 Introduction to Research in General

- Research in General

- Research Circle

- Tools of Research

- Methods: Quantitative or Qualitative

- The Product: Research Report or Papers

2 Original Unity of Philosophy and Science

- Myth Philosophy and Science: Original Unity

- The Myth: A Spiritual Metaphor

- Myth Philosophy and Science

- The Greek Quest for Unity

- The Ionian School

- Towards a Grand Unification Theory or Theory of Everything

- Einstein’s Perennial Quest for Unity

3 Evolution of the Distinct Methods of Science

- Definition of Scientific Method

- The Evolution of Scientific Methods

- Theory-Dependence of Observation

- Scope of Science and Scientific Methods

- Prevalent Mistakes in Applying the Scientific Method

4 Relation of Scientific and Philosophical Methods

- Definitions of Scientific and Philosophical method

- Philosophical method

- Scientific method

- The relation

- The Importance of Philosophical and scientific methods

5 Dialectical Method

- Introduction and a Brief Survey of the Method

- Types of Dialectics

- Dialectics in Classical Philosophy

- Dialectics in Modern Philosophy

- Critique of Dialectical Method

6 Rational Method

- Understanding Rationalism

- Rational Method of Investigation

- Descartes’ Rational Method

- Leibniz’ Aim of Philosophy

- Spinoza’ Aim of Philosophy

7 Empirical Method

- Common Features of Philosophical Method

- Empirical Method

- Exposition of Empiricism

- Locke’s Empirical Method

- Berkeley’s Empirical Method

- David Hume’s Empirical Method

8 Critical Method

- Basic Features of Critical Theory

- On Instrumental Reason

- Conception of Society

- Human History as Dialectic of Enlightenment

- Substantive Reason

- Habermasian Critical Theory

- Habermas’ Theory of Society

- Habermas’ Critique of Scientism

- Theory of Communicative Action

- Discourse Ethics of Habermas

9 Phenomenological Method (Western and Indian)

- Phenomenology in Philosophy

- Phenomenology as a Method

- Phenomenological Analysis of Knowledge

- Phenomenological Reduction

- Husserl’s Triad: Ego Cogito Cogitata

- Intentionality

- Understanding ‘Consciousness’

- Phenomenological Method in Indian Tradition

- Phenomenological Method in Religion

10 Analytical Method (Western and Indian)

- Analysis in History of Philosophy

- Conceptual Analysis

- Analysis as a Method

- Analysis in Logical Atomism and Logical Positivism

- Analytic Method in Ethics

- Language Analysis

- Quine’s Analytical Method

- Analysis in Indian Traditions

11 Hermeneutical Method (Western and Indian)

- The Power (Sakti) to Convey Meaning

- Three Meanings

- Pre-understanding

- The Semantic Autonomy of the Text

- Towards a Fusion of Horizons

- The Hermeneutical Circle

- The True Scandal of the Text

- Literary Forms

12 Deconstructive Method

- The Seminal Idea of Deconstruction in Heidegger

- Deconstruction in Derrida

- Structuralism and Post-structuralism

- Sign Signifier and Signified

- Writing and Trace

- Deconstruction as a Strategic Reading

- The Logic of Supplement

- No Outside-text

13 Method of Bibliography

- Preparing to Write

- Writing a Paper

- The Main Divisions of a Paper

- Writing Bibliography in Turabian and APA

- Sample Bibliography

14 Method of Footnotes

- Citations and Notes

- General Hints for Footnotes

- Writing Footnotes

- Examples of Footnote or Endnote

- Example of a Research Article

15 Method of Notes Taking

- Methods of Note-taking

- Note Book Style

- Note taking in a Computer

- Types of Note-taking

- Notes from Field Research

- Errors to be Avoided

16 Method of Thesis Proposal and Presentation

- Preliminary Section

- Presenting the Problem of the Thesis

- Design of the Study

- Main Body of the Thesis

- Conclusion Summary and Recommendations

- Reference Material

Share on Mastodon

- Anatomy & Physiology

- Astrophysics

- Earth Science

- Environmental Science

- Organic Chemistry

- Precalculus

- Trigonometry

- English Grammar

- U.S. History

- World History

... and beyond

- Socratic Meta

- Featured Answers

What are thesis, antithesis, synthesis? In what ways are they related to Marx?

COMMENTS

Thesis, antithesis, synthesis (or TAS) is a persuasive writing structure because it: Reduces complex arguments into a simple three-act structure. Complicated, nuanced arguments are simplified into a clear, concise format that anyone can follow. This simplification reflects well on the author: It takes mastery of a topic to explain it in it the ...

The thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad actually originated with Johann Fichte. dialectical method synthesis hegel. 1. History of the Idea. Thomas McFarland (2002), in his Prolegomena to Coleridge's Opus Maximum, identifies Immanuel Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (1781) as the genesis of the thesis/antithesis dyad. Kant concretises his ideas into:

Learn how Hegel used the structure of thesis, antithesis and synthesis to advance his philosophy, even though he never used these terms. See an example of how to apply this structure to a religious idea.

This synthesis then becomes a new thesis, continuing the process. Hegel applied this method to the evolution of ideas and history, arguing that progress occurs through such dialectical movement. Examples include the evolution from family (thesis) to civil society (antithesis) to state (synthesis), and from despotism (thesis) to democracy ...

The use of thesis and antithesis in literature enable the author to give more emphasis to an event or a theme in a story or play. Karl Marx used the thesis, antithesis and conclusion of a synthesis, to explain the evolution of communism. Using this format in debate helps to understand how two opposing ideals, around one debatable topic, can ...

Thesis and antithesis also are often used in philosophical discussions in order to reach new conclusions about accepted ways of thinking. First, the thesis or accepted way of thinking or acting, is expressed. Next, an antithesis is proposed that demonstrates conflicts or problems with the original thesis. The third step is referred to as synthesis.

Synthesis - the resolution of the conflict between thesis and antithesis In CISC 497, the rationales must be backed up with facts found during research on the topic. For the presentations, the thesis/antithesis/synthesis structure may be divided between speakers. For instance, one person could present the thesis, one the antithesis, and one

Thesis, antithesis, synthesis The classic pattern of academic arguments is: An Idea (Thesis) is proposed, an opposing Idea (Antithesis) is proposed, and a revised Idea incorporating (Synthesis) the opposing Idea is arrived at.

Hegel's most famous formulation of dialectics is the triadic structure of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis. According to Hegel, history, ideas, and reality itself unfold in a dialectical process. Each stage of development (thesis) creates its opposite (antithesis), and the tension between these opposites leads to a higher, more comprehensive ...

In general terms a thesis is a starting point, an antithesis is a reaction to it and a synthesis is the outcome. Marx developed the concept of historical materialism whereby the history of man developed through several distinct stages, slavery, feudalism, capitalism and in the future communism.. The movement from one stage to another could be explained by using thesis, antithesis and synthesis.