- The Open University

- Accessibility hub

- Guest user / Sign out

- Study with The Open University

My OpenLearn Profile

Personalise your OpenLearn profile, save your favourite content and get recognition for your learning

About this free course

Become an ou student, download this course, share this free course.

Start this free course now. Just create an account and sign in. Enrol and complete the course for a free statement of participation or digital badge if available.

4 Models of reflection – core concepts for reflective thinking

The theories behind reflective thinking and reflective practice are complex. Most are beyond the scope of this course, and there are many different models. However, an awareness of the similarities and differences between some of these should help you to become familiar with the core concepts, allow you to explore deeper level reflective questions, and provide a way to better structure your learning.

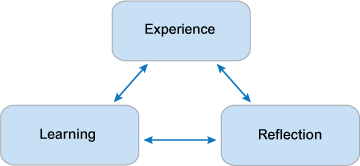

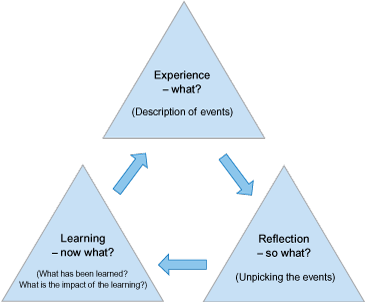

Boud’s triangular representation (Figure 2) can be viewed as perhaps the simplest model. This cyclic model represents the core notion that reflection leads to further learning. Although it captures the essentials (that experience and reflection lead to learning), the model does not guide us as to what reflection might consist of, or how the learning might translate back into experience. Aligning key reflective questions to this model would help (Figure 3).

This figure contains three boxes, with arrows linking each box. In the boxes are the words ‘Experience’, ‘Learning’ and ‘Reflection’.

This figure contains three triangles, with arrows linking each one. In the top triangle is the text ‘Experience - what? (Description of events)’. In the bottom-left triangle is the text ‘Learning - now what? (What has been learned? What is the impact of the learning?’. In the bottom-right triangle is the text ‘Reflection - so what? (Unpicking the events)’.

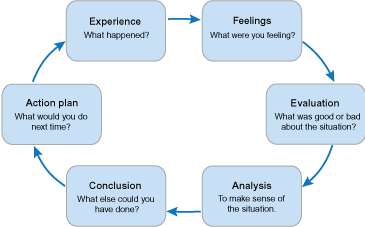

Gibbs’ reflective cycle (Figure 4) breaks this down into further stages. Gibbs’ model acknowledges that your personal feelings influence the situation and how you have begun to reflect on it. It builds on Boud’s model by breaking down reflection into evaluation of the events and analysis and there is a clear link between the learning that has happened from the experience and future practice. However, despite the further break down, it can be argued that this model could still result in fairly superficial reflection as it doesn’t refer to critical thinking or analysis. It doesn’t take into consideration assumptions that you may hold about the experience, the need to look objectively at different perspectives, and there doesn’t seem to be an explicit suggestion that the learning will result in a change of assumptions, perspectives or practice. You could legitimately respond to the question ‘what would you do or decide next time?’ by answering that you would do the same, but does that constitute deep level reflection?

This figure shows a number of boxes containing text, with arrows linking the boxes. From the top left (and going clockwise) the boxes display the following text: ‘Experience. What happened?’; ‘Feeling. What were you feeling?’; ‘Evaluation. What was good or bad about the situation?’; ‘Analysis. To make sense of the situation’; ‘Conclusion. What else could you have done?’; ‘Action plan. What would you do next time?’.

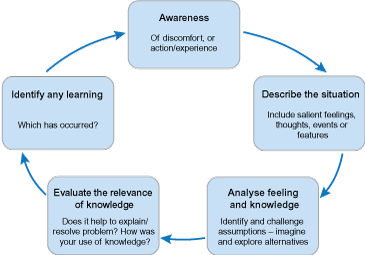

Atkins and Murphy (1993) address many of these criticisms with their own cyclical model (Figure 5). Their model can be seen to support a deeper level of reflection, which is not to say that the other models are not useful, but that it is important to remain alert to the need to avoid superficial responses, by explicitly identifying challenges and assumptions, imagining and exploring alternatives, and evaluating the relevance and impact, as well as identifying learning that has occurred as a result of the process.

This figure shows a number of boxes containing text, with arrows linking the boxes. From the top (and going clockwise) the boxes display the following text: ‘Awareness. Of discomfort, or action/experience’; ‘Describe the situation. Include saliant feelings, thoughts, events or features’; ‘Analyse feeling and knowledge. Identify and challenge assumptions - imagine and explore alternatives’; ‘Evaluate the relevance of knowledge. Does it help to explain/resolve the problem? How was your use of knowledge?’; ‘Identify any learning. Which has occurred?’

You will explore how these models can be applied to professional practice in Session 7.

Models of reflection you can use

There are many different models of reflection. They vary from the straightforward to the complex. Ultimately, though, all the models are based on the simple progression of thinking about what happened to you and what it means to you for the future.

However, you may be asked to write your reflection using a particular academic model of reflection. So, here is a handy guide to the most popular models of reflection that are widely used.

The ERA Cycle

The ERA Cycle was summarised by Professor Melanie Jasper in her book “Beginning Reflective Practice” as being: Experience – Reflection – Action .

We experience everything. You are experiencing reading this. You may have experienced drinking a coffee this morning as well. You might also have experienced a stunning lecture yesterday. Everything we do is an experience.

Sometimes you reflect on each experience. Sometimes you don’t. I doubt if you have reflected on that coffee you drank earlier – unless it triggered some kind of response because it was too hot, or tasted dreadfully. But if it was just your usual, everyday coffee, you didn’t think much about it. However, other experiences you do reflect upon. If you have been to an amazing lecture today, you may well have chatted with your friends about it afterwards and reflected on what it meant. So, some experiences get more of our attention and we think about them.

After we have thought about these more important experiences we then might go on to consider what it all means and what actions we might need to take. For example, if you did not have your usual coffee this morning and bought something else you might have experienced a more bitter taste. You would have reflected on that and thought you didn’t like it. Then you would consider the action you might take such as never buying it again…!

The simplicity of the ERA cycle is appealing because we can easily relate everything we do to it.

Borton’s Model

This model goes back to 1970 when the American schoolteacher, Terry Borton, wrote a book called Reach, Touch and Teach about his desire to make High School “as relevant, involving, and joyful as the learning each of us experienced when we were infants first discovering ourselves and our surroundings”. Borton describes three essential questions which need asking if we are to reflect on our learning effectively. These are “What?”, “So What?” and “Now What?”.

This model asks you to describe what happened. Then you consider what it means to you. Then you think about what you can do about it.

Driscoll’s Model

Some years after Borton’s book was published John Driscoll adapted the model specifically for clinical practice in nursing . Since then, the Driscoll Model has been widely used in the medical and health sectors. The Driscoll Model adds further questions as triggers for thinking about each of the main “what” questions that Borton suggested.

What? This includes trigger questions such as “What happened?”, “What did I do?” and “What was my reaction?”

So what? This has trigger questions including “So what did I feel at the time?”, “What do I feel now” and “What were the effects on me?”

Now what? This involves trigger questions like “Now what are the implications for me?” and “Now what is the main learning I take from this?”

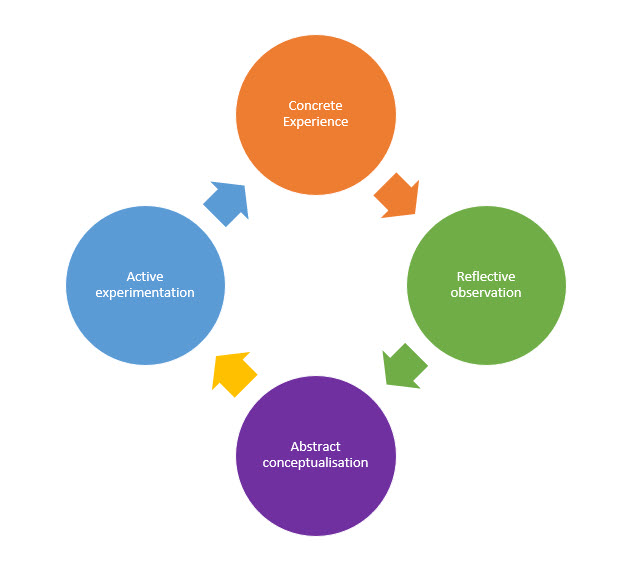

Kolb’s Experiential Cycle

The Kolb Experiential Cycle is not just a model of reflection. It is a theoretical model of how we learn.

The essence of Kolb is similar to the other models discussed so far. However, added here is the concept of going beyond reflecting and thinking about what we have experienced. What Kolb introduces is the notion of “active experimentation”.

Kolb’s Cycle begins with us experiencing something, as in the ERA model. Then, Kolb suggests we reflect on it. We think about what the experience means to us. The ERA model suggests we then consider how to act in the future. However, Kolb’s model essentially splits this into two stages. Kolb’s model suggests that having reflected on our experiences we then form abstract concepts about meanings. Then we change our behaviour according to those concepts to see if we have made a difference. That leads to new experiences, and we go around and around the cycle again and again.

Gibb’s Reflective Cycle

One of the most popular models of reflection is Gibb’s Reflective Cycle.

This extends the earlier models even further. The three steps of the ERA model have now become six steps.

Description: What happened?

Feelings: What did you feel and what did you think?

Evaluation: What was good or bad about the experience you described?

Analysis: What other impacts can you think about?

Conclusion: What could you have done instead?

Action plan: What would you do in future in the same situation?

Using models of reflection

There are many other models of reflection you may read about. They all have the same fundamental basis in common, though, which is the ERA model. You may be asked to write reflections using a particular model, so make sure you conduct all the steps necessary. If you are in the healthcare sector using the Driscoll Model is going to be commonplace.

However, models of reflection are just that – models. They have problems. They do not always match the circumstances of your studies. Equally, they suggest you have to follow the “cycle” in a particular order that might not be useful in your specific situation.

So, even though these models are popular they are not the “final word” on reflective practice. Good reflection has an impact. And if your way of producing that impact does not follow one of these models, then it doesn’t matter. Reflection is personal, so having a personal model of reflection is just fine.

Reflective Writing Tips has been compiled by Graham Jones, a UK university lecturer. Graham is a psychologist and has been teaching reflective thinking and reflective writing for more than 20 years to undergraduates and postgraduates.

How to Write a Reflective Essay

You’re probably used to responding to different sources in essays. For example, in an academic essay, you might compare two books’ themes, argue for or against a position, analyze a piece of literature, or persuade the reader with facts and statistics.

In one way, a reflective essay is similar to an academic essay. Like an academic essay, a reflective essay can discuss ideas and concepts from books, literature, essays, or articles. However, unlike an academic essay, it focuses on how your personal experience relates to these things.

Give your writing extra polish Grammarly helps you communicate confidently Write with Grammarly

What is a reflective essay?

Reflective essays are a type of personal essay in which the writer examines a topic through the lens of their unique perspective. Reflective essays are more subjective about their subjects than an academic essay, use figurative language, and don’t require academic sources. The purpose of a reflective essay is to explore and share the author’s thoughts, perspectives, and experiences.

Reflective essays are often written for college applications and cover letters as a way for the writer to discuss their background and demonstrate how these experiences shaped them into an ideal candidate. For example, a college applicant might write a reflective essay about how moving every few years because of their parent’s military service impacted their concept of home.

Sometimes, reflective essays are academic assignments. For example, a student may be assigned to watch a film or visit a museum exhibition and write a reflective essay about the film or exhibition’s themes. Reflective essays can also be pieces of personal writing, such as blog posts or journal entries.

Reflective essay vs. narrative essay

There are a few similarities between reflective essays and narrative essays. Both are personal pieces of writing in which the author explores their thoughts about their experiences. But here’s the main difference: While a narrative essay focuses on a story about events in the author’s life, a reflective essay focuses on the changes the author underwent because of those events. A narrative essay has many of the same elements as a fictional story: setting, characters, plot, and conflict. A reflective essay gets granular about the circumstances and changes driven by the conflict and doesn’t necessarily aim to tell a full story.

Reflective essays based on academic material

You might be assigned to write a reflective essay on an academic text, such as an essay, a book, or an article. Unlike a reflective essay about your own personal experiences, this type of reflective essay involves analysis and interpretation of the material. However, unlike in an analytical essay , the position you support is informed by your own opinion and perspective rather than solely by the text.

How to choose a topic

A reflective essay can be about any topic. By definition, a reflective essay is an essay where the writer describes an event or experience (or series of events or experiences) and then discusses and analyzes the lessons they derived from their experience. This experience can be about anything , whether big life events like moving to a new country or smaller experiences like trying sushi for the first time. The topic can be serious, lighthearted, poignant, or simply entertaining.

If your reflective essay is for an assignment or an application, you might be given a topic. In some cases, you might be given a broad area or keyword and then have to develop your own topic related to those things. In other cases, you might not be given anything. No matter which is the case for your essay, there are a few ways to explore reflective essay ideas and develop your topic.

Freewriting is a writing exercise where you simply write whatever comes to mind for a fixed period of time without worrying about grammar or structure or even writing something coherent. The goal is to get your ideas onto paper and explore them creatively, and by removing the pressure to write something submittable, you’re giving yourself more room to play with these ideas.

Make a mind map

A mind map is a diagram that shows the relationships between ideas, events, and other words related to one central concept. For example, a mind map for the word book might branch into the following words: fiction , nonfiction , digital , hardcover . Each of these words then branches to subtopics. These subtopics further branch to subtopics of their own, demonstrating just how deep you can explore a subject.

Creating a mind map can be a helpful way to explore your thoughts and feelings about the experience you discuss in your essay.

Real-life experiences

You can find inspiration for a reflective essay from any part of your life. Think about an experience that shifted your worldview or dramatically changed your daily routine. Or you can focus on the smaller, even mundane, parts of life like your weekly cleaning routine or trips to the grocery store. In a reflective essay, you don’t just describe experiences; you explore how they shape you and your feelings.

Reflective essay outline

Introduction.

A reflective essay’s introduction paragraph needs to include:

- A thesis statement

The hook is the sentence that catches the reader’s attention and makes them want to read more. This can be an unexpected fact, an intriguing statistic, a left-field observation, or a question that gets the reader’s mind thinking about the essay’s topic.

The thesis statement is a concise statement that introduces the reader to the essay’s topic . A thesis statement clearly spells out the topic and gives the reader context for the rest of the essay they’re about to read.

These aren’t all the things that a reflective essay’s introduction needs, however. This paragraph needs to effectively introduce the topic, which often means introducing a few of the ideas discussed in the essay’s body paragraphs alongside the hook and thesis statement.

Body paragraphs

Your essay’s body paragraphs are where you actually explore the experience you’re reflecting on. You might compare experiences, describe scenes and your emotions following them, recount interactions, and contrast it with any expectations you had beforehand.

Unless you’re writing for a specific assignment, there’s no required number of body paragraphs for your reflective essay. Generally, authors write three body paragraphs, but if your essay needs only two—or it needs four or five—to fully communicate your experience and reflection, that’s perfectly fine.

In the final section, tie up any loose ends from the essay’s body paragraphs. Mention your thesis statement in the conclusion, either by restating it or paraphrasing it. Give the reader a sense of completion by including a final thought or two. However, these thoughts should reflect statements you made in the body paragraphs rather than introduce anything new to the essay. Your conclusion should also clearly share how the experience or events you discussed affected you (and, if applicable, continue to do so).

6 tips for writing a reflective essay

1 choose a tone.

Before you begin to write your reflective essay, choose a tone . Because a reflective essay is more personal than an academic essay, you don’t need to use a strict, formal tone. You can also use personal pronouns like I and me in your essay because this essay is about your personal experiences.

2 Be mindful of length

Generally, five hundred to one thousand words is an appropriate length for a reflective essay. If it’s a personal piece, it may be longer.

You might be required to keep your essay within a general word count if it’s an assignment or part of an application. When this is the case, be mindful to stick to the word count—writing too little or too much can have a negative impact on your grade or your candidacy.

3 Stay on topic

A reflective essay reflects on a single topic. Whether that topic is a one-off event or a recurring experience in your life, it’s important to keep your writing focused on that topic.

4 Be clear and concise

In a reflective essay, introspection and vivid imagery are assets. However, the essay’s language should remain concise , and its structure should follow a logical narrative.

5 Stay professional

Although you aren’t bound to a formal tone, it’s generally best to use a professional tone in your reflective writing. Avoid using slang or overly familiar language, especially if your reflective essay is part of a college or job application .

6 Proofread

Before you hit “send” or “submit,” be sure to proofread your work. For this last read-through, you should be focused on catching any spelling or grammatical mistakes you might have missed.

Reflective essay FAQs

Reflective essays are a type of personal essay that examines a topic through the lens of thewriter’s unique perspective. They are more subjective about their subjects than an academic essay, use figurative language, and don’t require academic sources.

What’s the difference between a reflective essay and a narrative essay?

While a reflective essay focuses on its author’s feelings and perspectives surrounding events they’ve experienced or texts they’ve read, a narrative essay tells a story. A narrative essay might show changes the author underwent through the same conventions a fictional story uses to show character growth; a reflective essay discusses this growth more explicitly and explores it in depth.

What are example topics for a reflective essay?

- Moving abroad and adapting to the local culture

- Recovering from an athletic injury

- Weekly phone conversations with your grandmother

- The funniest joke you ever heard (and what made it so funny)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.18: Reflective Writing

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 58227

- Lumen Learning

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

- Examine the components of reflective writing

Reflective Writing

Reflective writing includes several different components: description, analysis, interpretation, evaluation, and future application. Reflective writers must weave their personal perspectives with evidence of deep, critical thought as they make connections between theory, practice, and learning. The steps below should help you find the appropriate balance among all these factors.

1st Step: Review the assignment

As with any writing situation, the first step in writing a reflective piece is to clarify the task. Reflective assignments can take many forms, so you need to understand exactly what your instructor is asking you to do. Some reflective assignments are short, just a paragraph or two of unpolished writing. Usually the purpose of these reflective pieces is to capture your immediate impressions or perceptions. For example, your instructor might ask you at the end of a class to write quickly about a concept from that day’s lesson. That type of reflection helps you and your instructor gauge your understanding of the concept.

Other reflections are academic essays that can range in length from several paragraphs to several pages. The purpose of these essays is to critically reflect on and support an original claim(s) about a larger experience, such as an event you attended, a project you worked on, or your writing development. These essays require polished writing that conforms to academic conventions, such as articulation of a claim and substantive revision. They might address a larger audience than you and your instructor, including, for example, your classmates, your family, a scholarship committee, etc. It’s important before you begin writing, that you can identify the assignment’s purpose, audience, intended message or content, and requirements.

2nd Step: Generate ideas for content

As you generate ideas for your reflection, you might consider things like:

- Recollections of an experience, assignment, or course

- Ideas or observations made during that event

- Questions, challenges, or areas of doubt

- Strategies employed to solve problems

- A-ha moments linking theory to practice or learning something new

- Connections between this learning and prior learning

- New questions that arise as a result of the learning or experience

- New actions taken as a result of the learning or experience

3rd Step: Organize content

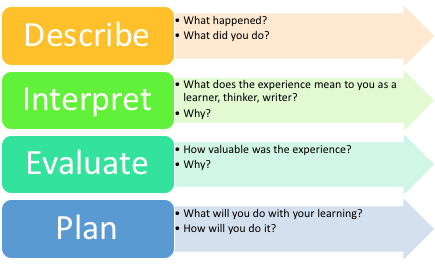

Researchers have developed several different frameworks or models for how reflective writing can be structured. For example, one method has you consider the “What?” “So what?” and “Now what?” of a situation in order to become more reflective. First, you assess what happened and describe the event, then you explain why it was significant, and then you use that information to inform your future practice. [1] [2] Similarly, the DIEP framework can help you consider how to organize your content when writing a reflective piece. Using this method, you describe what happened or what you did, interpret what it means, evaluate its value or impact, and plan steps for improving or changing for the future.

The DIEP Model of reflective writing

The DIEP model (Boud, Keogh & Walker,1985) organizes the reflection into four different components:

Remember, your goal is to make an interpretive or evaluative claim, or series of claims, that moves beyond obvious statements (such as, “I really enjoyed this project”) and demonstrates you have come to a deeper understanding of what you have learned and how you will use that learning.

In the example below, notice how the writer reflects on her initial ambitions and planning, the a-ha! moment, and then her decision to limit the scope of a project. She was assigned a multimodal (more than just writing) project, in which she made a video, and then reflected on the experience:

Student Example

Keeping a central focus in mind applies to multimodal compositions as well as written essays. A prime example of this was in my remix. When storyboarding for the video, I wanted to appeal to all college students in general. Within my compressed time limit of three minutes, I had planned to showcase numerous large points. It was too much. I decided to limit the scope of the topic to emphasize how digitally “addicted” college students are, and that really changed the project in significant ways.

4th Step: Draft, Revise, Edit, Repeat

A single, unpolished draft may suffice for short, in-the-moment reflections, but you may be asked to produce a longer academic reflection essay, which will require significant drafting, revising, and editing. Whatever the length of the assignment, keep this reflective cycle in mind:

- briefly describe the event or action;

- analyze and interpret events and actions, using evidence for support;

- demonstrate relevance in the present and the future.

The following video, produced by the Hull University Skills Team, provides a great overview of reflective writing. Even if you aren’t assigned a specific reflection writing task in your classes, it’s a good idea to reflect anyway, as reflection results in better learning.

You can view the transcript for “Reflective Writing” here (opens in new window) .

Check your understanding of reflective writing and the things you learned in the video with these quick practice questions:

https://h5p.cwr.olemiss.edu/h5p/embed/60

- Driscoll J (1994) Reflective practice for practise - a framework of structured reflection for clinical areas. Senior Nurse 14 (1):47–50 ↵

- Ash, S.L, Clayton, P.H., & Moses, M.G. (2009). Learning through critical reflection: A tutorial for service-learning students (instructor version). Raleigh, NC. ↵

Contributors and Attributions

- Process of Reflective Writing. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Reflective Writing. Provided by : SkillsTeamHullUni. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QoI67VeE3ds&feature=emb_logo . License : Other . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

- Frameworks for Reflective Writing. Authored by : Karen Forgette. Provided by : University of Mississippi. License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

Reflective writing: Reflective essays

- What is reflection? Why do it?

- What does reflection involve?

- Reflective questioning

- Reflective writing for academic assessment

- Types of reflective assignments

- Differences between discursive and reflective writing

- Sources of evidence for reflective writing assignments

- Linking theory to experience

- Reflective essays

- Portfolios and learning journals, logs and diaries

- Examples of reflective writing

- Video summary

- Bibliography

On this page:

“Try making the conscious effort to reflect on the link between your experience and the theory, policies or studies you are reading” Williams et al., Reflective Writing

Writing a reflective essay

When you are asked to write a reflective essay, you should closely examine both the question and the marking criteria. This will help you to understand what you are being asked to do. Once you have examined the question you should start to plan and develop your essay by considering the following:

- What experience(s) and/or event(s) are you going to reflect on?

- How can you present these experience(s) to ensure anonymity (particularly important for anyone in medical professions)?

- How can you present the experience(s) with enough context for readers to understand?

- What learning can you identify from the experience(s)?

- What theories, models, strategies and academic literature can be used in your reflection?

- How this experience will inform your future practice

When structuring your reflection, you can present it in chronological order (start to finish) or in reverse order (finish to start). In some cases, it may be more appropriate for you to structure it around a series of flashbacks or themes, relating to relevant parts of the experience.

Example Essay Structure

This is an example structure for a reflective essay focusing on a single experience or event:

When you are writing a reflective assessment, it is important you keep your description to a minimum. This is because the description is not actually reflection and it often counts for only a small number of marks. This is not to suggest the description is not important. You must provide enough description and background for your readers to understand the context.

You need to ensure you discuss your feelings, reflections, responses, reactions, conclusions, and future learning. You should also look at positives and negatives across each aspect of your reflection and ensure you summarise any learning points for the future.

- << Previous: Reflective Assessments

- Next: Portfolios and learning journals, logs and diaries >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/reflectivewriting

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Reflective Practice & Reflective Writing

- What is Reflective Practice

- Barriers to Reflecting

Models of Reflection

- Reflection for Learning

- Reflective Writing

- Useful Resources

Further Resources

- A Handbook of Reflective and Experiential Learning by Jennifer A. Moon ISBN: 9780415335164 Publication Date: 2004-06-15 This handbook acts as an essential guide to understanding and using reflective and experiential learning - whether it be for personal or professional development, or as a tool for learning.

- Gibb's Reflective Cycle

- Kolb's Experiential Learning Model

- Driscoll's Model

Models provide a framework to guide you through the steps involved in reflection. Models can be basic, like Driscoll’s, which is a three step plan or much more detailed and structured such as Gibb’s model, which has six steps. The models share similar characteristics such as; descriptive, analytical and critical sections and a final section that outlines a plan for the future.

Each tab in this section provides details of the model and a short video how you might use it.

Image; Details

A worked example of using Gibb's Reflective Cycle

Image:Details

Overview of Kolb's Experiential Learning

Image Details

Overview of Driscoll's Reflective Model

- << Previous: Barriers to Reflecting

- Next: Reflection for Learning >>

- Last Updated: Sep 7, 2023 4:13 PM

- URL: https://tudublin.libguides.com/reflective_practice

Reflective Writing

- Reflective writing

- Sessions and recordings

- What is reflective writing?

- Planning reflective writing

- Frameworks and models

- Comparison to the literature

- Critical reflective writing

- Quick resources

- E-learning and books

- SkillsCheck This link opens in a new window

Reflective Frameworks & Models

There are many reflective frameworks to choose from. See the comprehensive Reflective Writing Guide from the University of Hull for information about some of the most popular models. When selecting a framework, look at your brief, your word count, and the strengths and weaknesses of each model. You can also justify why you chose the model in the introduction to your essay. This evidences your critical thinking.

- Reflective Example - Gibbs

- Reflective Example - Rolfe et al.

- << Previous: Planning reflective writing

- Next: Comparison to the literature >>

Adsetts Library

Collegiate library, sheffield hallam university, city campus, howard street, sheffield s1 1wb, contact us / live chat, +44 (0)114 225 2222, [email protected], accessibility, legal information, privacy and gdpr, login to libapps.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

This cyclic model represents the core notion that reflection leads to further learning. Although it captures the essentials (that experience and reflection lead to learning), the model does not guide us as to what reflection might consist of, or how the learning might translate back into experience.

There are many different models of reflection. They vary from the straightforward to the complex. Ultimately, though, all the models are based on the simple progression of thinking about what happened to you and what it means to you for the future. However, you may be asked to write your reflection using a particular academic model of reflection.

is purely to show how a reflective assignment might look. Assignment – write a reflection of around 1000 words about an incident which occurred during the first few weeks of your teaching placement. Use Gibbs’ model, and structure your assignment using Gibbs’ headings. Description . I am currently on a teaching practice placement in

May 17, 2023 · Or you can focus on the smaller, even mundane, parts of life like your weekly cleaning routine or trips to the grocery store. In a reflective essay, you don’t just describe experiences; you explore how they shape you and your feelings. Reflective essay outline Introduction. A reflective essay’s introduction paragraph needs to include: A hook

Jul 22, 2023 · The DIEP Model of reflective writing. The DIEP model (Boud, Keogh & Walker,1985) organizes the reflection into four different components: Figure 1. The DIEP model for reflective thinking and writing has you first describe the situation, interpret it, evaluate it, then plan what to do with that new information.

Jan 19, 2024 · Frameworks of reflective practice. If your assignment requires you to make reference to a framework (or 'model') of reflective practice, you will need to choose a framework through which to structure your assignment. Each framework establishes a different approach to reflection and will require you to approach your writing differently.

Based on Graham Gibbs’s model of reflection. When writing a reflective essay, you might need to analyze a particular object, event, or concept. It is crucial to remember that a reflective essay isn’t just a summary of your observations. It should have an in-depth analysis of whatever you write about.

Jan 19, 2024 · When you are asked to write a reflective essay, you should closely examine both the question and the marking criteria. This will help you to understand what you are being asked to do. Once you have examined the question you should start to plan and develop your essay by considering the following:

Jun 15, 2004 · Models can be basic, like Driscoll’s, which is a three step plan or much more detailed and structured such as Gibb’s model, which has six steps. The models share similar characteristics such as; descriptive, analytical and critical sections and a final section that outlines a plan for the future.

There are many reflective frameworks to choose from. See the comprehensive Reflective Writing Guide from the University of Hull for information about some of the most popular models. When selecting a framework, look at your brief, your word count, and the strengths and weaknesses of each model.