Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › British Literature › Analysis of Henry James’s Daisy Miller

Analysis of Henry James’s Daisy Miller

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on July 9, 2022

Originally subtitled “A Study,” this novella was first published by Leslie Stephen, the father of Virginia Woolf , in the Cornhill Magazine . The choice of a British press cost Henry James his American rights. The sheer amount of pirated versions, however, hints at the succès de scandale the book turned out to be in the literary marketplace on both sides of the Atlantic: Daisy-Millerites celebrated the textual subtleties of observation, while the (less numerous) anti-Daisy-Millerites disparaged it as a foreign and all-too-abrasive judgment on American citizens abroad.

The story of the young American naif sojourning in Europe was generally received as a theatrical comedy or tragicomedy of manners, even more so since James himself reworked his plot into a three-act comedy in 1883, characteristically failing at the dramatic medium. Critics have often commented on the text’s uncomfortable blend of the comic and mythic and the overly melodramatic structure peppered with a substantial amount of symbolically significant names, like “Daisy,” the spring flower suggesting freshness and innocence; a would-be lover whose name puns on winter-born; an inappropriately immobile Mrs. Walker; and the conflagration of old and new money imagery in the hotel’s name, Trois Couronnes.

Yet taking into account that even a literary master may accommodate effects generally associated with sentimental domestic traditions, it seems more fruitful to approach the text as a cultural study by an artistic expatriate. Daisy Miller furnishes an early example of James’s so-called international theme, which juxtaposes unsophisticated American travelers with an old Europe brimming uneasily with a profound, often strikingly carnal, knowledge of the world. As a structuring device, this theme traces the choreographies of curiously transitory identities, which circulate across boundaries of all sorts. Moreover, the characteristically Jamesian point of view can already be detected in the use of a third-person narrative voice as a central intelligence, embodied in the young American, Frederick Winterbourne. The novella thus focuses on the observer, and Daisy as the object of the gaze is accessible for the reader only through his jaundiced eyes. Winterbourne’s voice, however, is still framed by that of a first-person narrator whose minute hesitations and slips of the tongue prevent readers from an unproblematic identification with the male protagonist, calling into question his reliability as a storyteller and his frequently clinical judgments.

The novella begins with Winterbourne, just come over from Geneva, seated in the garden of the fashionably cosmopolitan hotel Trois Couronnes in the Swiss resort of Vevey. A disconnected bachelor with voyeuristic leanings, he is fully absorbed by his gentlemanly existence whose dated moral parameters account for his difficulty in understanding a fresh young woman, Daisy Miller, who is literally crossing his path.

The girl, with her fragmentary social know-how, seems on conscious display, adorned with a fan as an image of both feminine grace and challenge. In a recourse to a trope of realist writing, the text presents her as an unprotected daughter and a victim of flawed nurturing. She is associated with an uncultivated and alarmingly dysfunctional family background: Her father remains a blank, being far off on business; her mother is a hypochondriac dressing in Daisy’s discarded clothes; her younger brother is a xenophobic, provincial, and aggressively newly rich brat.

Fascinated with her good looks and confused by her candor, Winterbourne tests her to see to what violation of social codes she can be lured. Yet her behavior— when she upholds her suggestion of a boat trip à deux to Chillon, paying no heed to the warnings of the courier Eugenio, and even urges Winterbourne to come and see her in Rome—threatens to overwhelm the neat categories of her suitor’s obsessively itemizing mind. In his desperate attempts to make her legible by fi nding epithets and attaching labels, he seeks the feedback of his ilk in the expatriate American community of which his aunt Mrs. Costello is a crucial part. Here, among people more European than the Europeans, Daisy is unremittingly judged for letting herself be talked about in picking up chance acquaintances.

The subsequent geographical shift notwithstanding, rumors about Daisy fill the air in Rome as well. Confronted with her Italian cavalier, the gentleman lawyer Giovanelli, Winterbourne suddenly finds himself a substitute Eugenio dedicated to safeguard her. When the young woman is caught walking with both men in the Pincian Gardens in a blatant trespass of codes of propriety and refuses to heed Mrs. Walker’s urgent remonstrations, the American diaspora finally closes its ranks by ostracizing Daisy publicly as “damaged goods.” The object of this moral outrage, however, defiantly and deliberately leaves Winterbourne still at sea with regard to her possible engagement with Giovanelli.

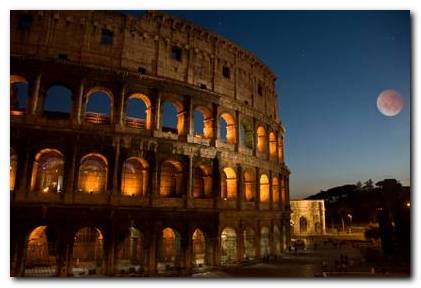

Moreover, she even ventures to pay a nocturnal visit to the Colosseum with the Italian, even though the sacrificial site is notorious for its miasmal atmosphere. Winterbourne overhears their plans and seems to arrive finally at his sought-for ultimate reading of Daisy. He settles on the worthlessness of his former object of attention, and this pivotal scene is followed by the laconic report of her death by fever, which she contracted during her nightly excursion. Ambiguously, her loss of life in spring is either sentimentally readable as a willed suicide motivated by Winterbourne’s rejection of her or as a mere outcome of her imprudence. Winterbourne himself admits that confusion as to the young woman’s character still lingers in his mind, even more so since Daisy’s mother fulfills her daughter’s last wish in informing him that Daisy was never Giovanelli’s fiancée.

With his return to Geneva, however, which seems motivated by some foreign lady who is sojourning there, the plot comes full circle: Any illusion of personal development is shattered, as Winterbourne continues in his determination to censor otherness in order to maintain the social entropy that is required for his survival as a gentleman gigolo.

In this novella about the male gaze, everybody is busy forging fictions about others to such an extent that none of the narratives can be authenticated. Always alive to alternative options, the text resists the very conventions of realistic characterization on which it relies. The central consciousness is forever failing to arrive at ultimate certainty; the excess of sobriquets attached to Daisy drains them of any defining function. The gossip that characterizes the settings of Rome and Geneva may well look back on long traditions of moral absolutism, be they Catholic or Calvinist, yet it never fully manages to blot out Daisy’s plain formulation of relativity: “People have different ideas.”

The novella furnishes an example of indeterminacy and the provisionality of identities that came to be registered as a distinctively Jamesian hallmark. Moreover, in setting its characters afloat on a sea of rumors while telling a tale of failed communication and epistemological insecurity, the text anticipates a central concern of modernist writing.

Analysis of Henry James’s Novels

BIBLIOGRAPHY Bell, Millicent. Meaning in Henry James. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1991. Fogel, Daniel Mark. Daisy Miller: A Dark Comedy of Manners. Boston: Twayne, 1990. Graham, Kenneth. “Daisy Miller: Dynamics of an Enigma.” In New Essays on Daisy Miller and The Turn of the Screw, edited by Vivian R. Pollak, 35–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. James, Henry. Daisy Miller and Other Stories. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998. Weisbuch, Robert. “Henry James and the Idea of Evil.” In The Cambridge Companion to Henry James, edited by Jonathan Freedman, 102–119. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Share this:

Categories: British Literature , Literature , Novel Analysis , Short Story

Tags: Analysis of Henry James's Daisy Miller , appreciation of Henry James's Daisy Miller , guide of Henry James's Daisy Miller , Henry James , Henry James's Daisy Miller , Henry James's Daisy Miller criticism , Henry James's Daisy Miller essays , Henry James's Daisy Miller guide , Henry James's Daisy Miller notes , Henry James's Daisy Miller plot , Henry James's Daisy Miller story , Henry James's Daisy Miller structure , Henry James's Daisy Miller summary , Henry James's Daisy Miller themes , notes of Henry James's Daisy Miller , plot of Henry James's Daisy Miller , structure of Henry James's Daisy Miller , themes of Henry James's Daisy Miller

Related Articles

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Alex Garcia Topete

The spectator and the muses, daisy miller: a study of american realism.

At first reading, Henry James’s Daisy Miller: A Study seems to be just another romance—a story about lovers and wooing told in a way suitable to be read aloud as an engaging pastime. Because of the structure of its plot and the elements it encompasses (such as the pursuit of the love interest or the fancy European locales), the novella could easily be misunderstood as a Romantic piece, for it shares vaguely some of the traits of that movement. However, when examined more thoroughly, the details in Daisy Miller of how its elements function to make the story unfold reveal a general lack of idealization (idealization which would be essential for Romanticism) proper to the Realistic movement to which the novella belongs.

Daisy Miller first lacks idealization in the very nature and development of the lead characters’ romance, since it doesn’t overtly involve “higher” emotions such as passionate and undying love. Rather, the relationship between Winterbourne and Daisy Miller arises from a sort of mutual curiosity. Winterbourne becomes “amused, perplexed, and decidedly charmed” (James, 118) with Mrs. Miller because of her free spirit, her uncultivated manners, and her being a compatriot in foreign lands (and her beauty, to a degree), all which contrast with the stern standards of the Calvinist society of his hometown, Geneva, which had “dishabituated him to the American tone.” (James, 118). His main drive is to understand his peculiar object of desire—the American flirt.

Daisy Miller’s interest for her suitor, on the other hand, springs from her general curiosity about Europe and its society, not from an interest in marriage or romantic engagements. Daisy wants to explore, to go places (such as the Chateau Chillon), and to be part of society as she is back in New York, for she is “very fond of society, and [she has] always had a great deal of it…a great deal of gentlemen’s society.” (James, 117-118). Her mother and brother, with whom she’s travelling, don’t entirely share her desire for discovery, nor do they participate in its fulfillment. Hence, the relationship between the two characters develops as a mutual enhancement: Winterbourne learns about “the regular conditions and limitation of one’s intercourse with a pretty American flirt” (James, 118) while he serves as companion and guide for Miss Miller when they meet. Their courtship is no love affair but (as the title suggests) a mutual study of culture and character.

Overall, the romantic aspect of the characters’ relationship, which is mostly implied by the narrative that reveals Winterbourne’s interest for the girl, reveals to be meek at best, for neither character displays or expresses great affection for the other, externally or internally. For instance, Winterbourne barely defends Daisy’s reputation when his aunt, Mrs. Costello, bashes it, at times submitting to her judgments (James, 122); and Daisy “goes about alone with her foreigners” (James, 133) in Rome, undermining the idea that Winterbourne might mean to her a special escort of any kind. Their courtship, limited to staggered days and a few encounters, never culminates in either an ideal, grandiose love proclamation or a passionate sex encounter—their courtship simply comprises their whole relationship.

Not only do Winterbourne and Daisy fail to be Romantic heroes or the epitome of passionate love, all the supporting characters are presented far from the ideals of what their roles would be under Romantic standards. Randolph, the little brother, and Mrs. Miller, the mother, long for America rather than enjoy the trip the way that people of their wealth should. Moreover, they long for America not because they miss some ideal of home, but because in America Randolph would get candy (James, 115) and Mrs. Miller would have Dr. Davies, the family physician, tending her illnesses and aches (James, 134)—both unsophisticated and superficial reasons. The family as a whole seems and acts so uncultivated that even their compatriots abroad shun them despite their wealth and rank back home, calling them “very dreadful people” (James, 133)—disdain expected more from the stuck-up English aristocracy than from the seemingly cosmopolitan Americans.

Winterbourne’s aunt, Mrs. Costello, who first shuns the Millers, has social prejudices which don’t allow her to even meet the possible romantic interest of her (presumably) beloved nephew. In spite of Winterbourne being more loyal and caring than her own children, she refuses to comply to Winterbourne’s request of meeting Daisy simply because “They are the sort of Americans that one does one’s duty by not—by not accepting.” (James, 121). In Daisy Miller , social scorn not only exists—it rules and isn’t ideally debunked or defeated by love and individuality.

Mr. Giovanelli, Daisy’s Roman suitor, fails to be the epitome of gallantry too. He does have the manners and etiquette of a gentleman, but his intentions seem questionable due to his reputation as a chaser of American heiresses with whom he had learned English so well (James, 139). His worst display of non-gallantry and selfishness happens towards the conclusion of the story, when he accompanies Daisy to the Coliseum at night despite the danger of the Roman fever (James, 154). Giovanelli claims twice that he took Daisy there (which led her to become ill and die) and disregarded the danger because he didn’t fear for himself (James, 154, 156), thus hinting at his selfishness and lack of strong emotional attachment to Daisy.

The Roman fever that killed Daisy also belongs to the details that portray Europe as a non-idealistic place: Rome is an ill-ridden city with a judgmental society which is just as pernicious as the epidemic; scammers and money-grubbing suitors populate all of Italy; and Swiss spas attract tourists but lack liveliness while Calvinist Geneva chokes liveliness out of those who live in it (such as Winterbourne). Only the ship in which the Miller’s travelled, “The City of Richmond,” is presented favorably—through the opinion of a young boy who had fun and enjoyed the trip except for its destination.

Maybe the conclusion of the novella falls farthest from any sort of ideal, considering that Daisy Miller ends with a courtship instead of a full romance; that the main female character dies suddenly; that Daisy leaves with her mother only a meek and unclear dying-words message for Winterbourne (James, 156); and that Winterbourne regrets “his mistake” and moves on with his life at Geneva mostly unaffected (James, 157).

Despite its apparent Romantic plot, Daisy Miller cannot be deemed romantic when love is so weak or Romantic when emotions are so absent, social constraints succeed at keeping the couple apart, and existence appears unjust and imperfect. Ultimately, all the bleakness of the world and the flaws of the characters in Daisy Miller exist to bring the story closer to the reality of the late 1800s and put that world into perspective—the perspective of a Realistic study.

Works Cited

James, Henry. Daisy Miller: A Study. New York: Pearson Custom Publishing, 1878.

Dallas, TX. June 2008.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Information Science and Technology

- Social Issues

Home Essay Samples Literature

Essay Samples on Daisy Miller

Analysis of the misunderstandings surrounding the main heroine from henry james’ novel daisy miller.

In Henry James’ Daisy Miller, the remark made by the novel regarding Winterbourne’s initial observation of daisy is that Winterbourne could not clearly read Daisy’s face. According to the novel, Winterbourne made a number of observations regarding Daisy immediately after encountering her, one of which...

- Daisy Miller

Literary Realism in Henry James' Novel "Daisy Miller"

Realism is the representation of a person, thing, or situation that is true to life and as explained by Norris, “..Is the kind of fiction that confines itself to the type of normal life” (Norris 811). As Frank Norris describes, it is used as a...

The Equation of Illness as a Form of Immunity in Henry James' Daisy Miller

Henry James was, after all, a physical man. Throughout his childhood and young adulthood, James was deeply affected by the drama of competing illnesses enacted in his family: William suffered from neurasthenia and amusia; Wilkinson was frightfully wounded in the Civil War; Alice struggled with...

- Literature Review

The Character Analysis of Daisy's Life in Daisy Miller by Henry James

There are quite a few characters in this story, but for now lets mainly focus on Daisy Miller the main character. Daisy was an American girl, rich and beautiful. She came from uptown New York, but she started traveled Europe with her family. Her mom,...

Best topics on Daisy Miller

1. Analysis Of The Misunderstandings Surrounding The Main Heroine From Henry James’ Novel Daisy Miller

2. Literary Realism in Henry James’ Novel “Daisy Miller”

3. The Equation of Illness as a Form of Immunity in Henry James’ Daisy Miller

4. The Character Analysis of Daisy’s Life in Daisy Miller by Henry James

Stressed out with your paper?

Consider using writing assistance:

- 100% unique papers

- 3 hrs deadline option

- Sonny's Blues

- A Raisin in The Sun

- Hidden Intellectualism

- William Shakespeare

- A Long Way Gone

- American Born Chinese

- Tragic Hero

- Black Men And Public Space

Need writing help?

You can always rely on us no matter what type of paper you need

*No hidden charges

100% Unique Essays

Absolutely Confidential

Money Back Guarantee

By clicking “Send Essay”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement. We will occasionally send you account related emails

You can also get a UNIQUE essay on this or any other topic

Thank you! We’ll contact you as soon as possible.

- Ask LitCharts AI

- Discussion Question Generator

- Essay Prompt Generator

- Quiz Question Generator

- Literature Guides

- Poetry Guides

- Shakespeare Translations

- Literary Terms

Daisy Miller

Henry james.

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Henry James's Daisy Miller . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

Daisy Miller: Introduction

Daisy miller: plot summary, daisy miller: detailed summary & analysis, daisy miller: themes, daisy miller: quotes, daisy miller: characters, daisy miller: symbols, daisy miller: literary devices, daisy miller: theme wheel, brief biography of henry james.

Historical Context of Daisy Miller

Other books related to daisy miller.

- Full Title: Daisy Miller

- When Written: 1877-1878

- Where Written: London

- When Published: In serialized magazine form between June and July 1878; in book form later that year.

- Literary Period: Literary realism

- Genre: Novella

- Setting: Vevay, Switzerland and Rome, Italy

- Climax: Winterbourne discovers Daisy with her Italian admirer, Mr. Giovanelli, wandering the Coliseum late at night, risking illness in addition to her reputation.

- Antagonist: In some ways, the women in Rome who band against Daisy, judging and condemning her because of her social improprieties, can be considered to be Daisy’s antagonists. But Daisy herself can also be seen as an antagonist to the very way of life sketched out by Henry James in the novella.

- Point of View: The novella, written in the third person, distinguishes the narrator from Winterbourne, although it cleaves closely to Winterbourne’s perspective. The narrator also often adopts a character’s point of view and speaking style without directly quoting him or her, leading to a greater collapse between narrator and characters.

Extra Credit for Daisy Miller

Upstaged: Henry James attempted to gain wider public success by writing for the stage, but his play, Guy Domville, was a disaster. It was ridiculed by the public when it was staged in 1895.

All in the Family : Henry’s brother, William James, was perhaps the most well-known philosopher and psychologist in the United States in the later part of the nineteenth century, and indeed is often considered the first modern American psychologist.

- Quizzes, saving guides, requests, plus so much more.

Tutorials, Study Guides & More

Daisy Miller

November 4, 2011 by Roy Johnson

tutorial, commentary, study resources, and web links

Daisy Miller is one of Henry James’s most famous stories. It was first published in the Cornhill Magazine in 1878 by Leslie Stephen (Virginia Woolf’s father) and became instantly popular. It was reprinted several times within a couple of years, and it was even pirated in Boston and New York. On the surface it’s a simple enough tale of a spirited young American girl visiting Europe. She is a product of the New World, but her behaviour doesn’t sit easily with the more conservative manners of her fellow expatriates in Europe. She pushes the boundaries of acceptable behaviour to the limit, and ultimately the consequences are tragic.

the Colosseum in moonlight

Daisy Miller – critical commentary

Story or novella?

Daisy Miller represents a difficult case for making distinctions between the long short story and the novella. Henry James himself called it a ‘short chronicle’, but as a matter of fact it was rejected by the first publisher he sent it to on the grounds that it was a ‘nouvelle’ – that is, too long to be a short story, and not long enough to be a novel.

It should be remembered that the concept of the novella only emerged in the second half of the nineteenth century, and publishers were sceptical about its commercial appeal. This was the age of three-volume novels, serial publications, and magazine stories which were written to be read at one sitting.

If it is perceived as a long short story, then the basic narrative line becomes ‘a young American girl is too forthright for her own good in unfamiliar surroundings and eventually dies as a result’. This seems to trivialize the subject matter, and reduce it to not much more than a cautionary anecdote.

The case for regarding it as a novella is much stronger. Quite apart from the element of length (30,000 words approximately) it is a highly structured work. It begins with Winterbourne’s arrival from Geneva, and it ends with his return there. It has two settings – Vevey and Rome. Daisy travels from Switzerland ‘over the mountains’ into Italy and Rome, one of the main centres of the Grand Tour. And it has two principal characters – Winterbourne and Daisy. It also has two interlinked subjects. One is overt – Winterbourne’s attempt to understand Daisy’s character. The second is more complex and deeply buried – class mobility, and the relationship between Europe and America.

Class mobility

Daisy’s family are representatives of New Money. Her father, Ezra B. Miller is a rich industrialist. He has made his money in unfashionable but industrial Schenectady, in upstate New York. Having made that money, the family have wintered in fashionable New York City. This nouveau riche experience has given Daisy the confidence to feel that she can act as she wishes.

But the upper-class social group in which she is mixing have a different set of social codes. They are in fact imitating those of the European aristocracy to which they aspire. In this group a young woman should be chaperoned in public, and she must not even appear to spend too long in the company of an eligible bachelor because this might compromise her reputation.

Daisy has the confidence and the social dynamism provided by her father’s industrial-based money back in Schenectady, but she is denied permanent entry into the upper-class society in which she is mixing because she flouts its codes of behaviour.

Conversely, Winterbourne is attracted to Daisy’s frank and open manner, but he does not understand her – until it is too late. In fact he fails to recognise the clear opportunities she offers him to make a fully engaged relationship, and as she rightly observes, he is ‘too stiff’ to shift from his conservative attitudes. The text does not make clear his source of income, but he obviously feels at home with the upper-class American expatriates, and his return to Geneva at the end of the novella to resume his ‘studies’ underscores his wealthy dilettantism.

He is trapped in his upper-class beliefs in a way that Daisy is not in hers. She has the confidence of having made a transition from one class into another at a higher level. She has a foot in both camps – but her tragedy is that she fails to recognise that she cannot enjoy the benefits of the higher class without accepting the restrictions membership will impose on her behaviour.

Daisy Miller – study resources

Daisy Miller – plot summary

Part I . Frederick Winterbourne, an American living in Geneva is visiting his aunt in Vevey, on Lake Leman. In the hotel garden he meets Daisy Miller via her young brother Randolph. He is much taken with her good looks, but puzzled by her forthright conversation. He offers to show her the Castle of Chillon at the end of the lake.

Part III . Some weeks later on his arrival in Rome, Winterbourne’s friend Mrs Walker warns him that Daisy is establishing a dubious reputation because of her socially unconventional behaviour. Daisy joins them, and Winterbourne insists on accompanying her when she leaves to join a friend alone in public. He disapproves of the friend Signor Giovanelli who he sees as a lower-class fortune hunter, and Mrs Walker even tries to prevent Daisy from being seen alone in public with men.

Part IV . The American expatriate community resent Daisy’s behaviour, and Mrs Walker then snubs her publicly at a party they all attend. Winterbourne tries to warn Daisy that she is breaking the social conventions, but she insists that she is doing nothing wrong or dishonourable. He defends Daisy’s friendship with Signor Giovanelli to her American critics. Finally, Winterbourne encounters Daisy with Giovanelli viewing the Colosseum by moonlight. Winterbourne insists that she go back to the hotel to avoid a scandal. She goes under duress, but she has in fact contracted malaria (‘Roman Fever’) from which she dies a few days later. At the funeral Giovanelli reveals to Winterbourne that he knew that Daisy would never have married him. Winterbourne realises that he has made a mistake in his assessment of Daisy, but he ‘nevertheless’ returns to live in Geneva.

Henry James – portrait by John Singer Sargeant

Daisy Miller – principal characters

Daisy miller – film adaptation.

Directed by Peter Bogdanovich (1974)

Starring Cybill Shepherd and Barry Brown

Daisy Miller – further reading

Biographical

Critical commentary

Other works by Henry James

© Roy Johnson 2012

Henry James – web links

Get in touch.

- Advertising

- T & C’s

- Testimonials

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Daisy Miller — Daisy Miller: the subject of a research, and a narrative objective

Daisy Miller: The Subject of a Research, and a Narrative Objective

- Categories: Daisy Miller

About this sample

Words: 1039 |

Pages: 2.5 |

Published: Jun 29, 2018

Words: 1039 | Pages: 2.5 | 6 min read

If she looked another way when he spoke to her, and seemed not particularly to hear him, this was simply her habit, her manner . . . He had a great relish for feminine beauty; he was addicted to observing and analyzing it; and as regards this young lady’s face he made several observations. It was not at all insipid, but it was not exactly expressive; and though it was eminently delicate, Winterbourne mentally accused it – very forgivingly – of a want of finish. (1504)

And then he came back to the question whether this was in fact a nice girl. Would a nice girl – even allowing for her being a little American flirt – make a rendezvous with a presumably low-lived foreigner? …It was impossible to regard her as a perfectly well conducted young lady; she was wanting in a certain indispensable delicacy. It would therefore simplify matters greatly to be able to treat her as the object of one of those sentiments, which are called by romancers “lawless passions”. (1524)

Winterbourne stopped, with a sort of horror; and, it must be added, with a sort of relief. It was as if a sudden illumination had been flashed upon the ambiguity of Daisy’s behavior and the riddle had become easy to read. She was a young lady whom a gentleman need no longer be at pains to respect . . . He felt angry with himself that he had bothered so much about the right way of regarding Miss Daisy Miller.” (1536)

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1.5 pages / 767 words

3 pages / 1428 words

2.5 pages / 1035 words

6 pages / 2830 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

War, deeply intertwined with human existence, overshadows action with impasse and ideals with sterility. Although war results in the facade of victory for one side, no true winner exists, because under this triumphant semblance [...]

“For he alone knew, what no other initiate knew, how easy it was to fast. It was the easiest thing in the world.” Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist” What does it mean to willfully fast, or to deny hunger, the most fundamental of [...]

“These are but the spirit of things that have been.” The metaphorical words of the Ghost of Christmas Past are typical of Dickens’ melodramatic writing style. Set in Victorian England, a time rife with greed and social [...]

Ernest Hemingway called his novel A Farewell to Arms his “Romeo and Juliet.” The most obvious similarity between these works is their star-crossed lovers, as noted by critic Carlos Baker; another is that the deaths of both [...]

In Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms, Frederic Henry finds in his relationship with Catherine Barkley – a relationship they think of as a marriage – safety, comfort, and tangible sensations of love: things that conventional [...]

When a man’s name is synonymous with greed and misery, most readers would not associate him with the shining image of a hero. The hero’s journey is a classic literary pattern in which a character goes on an adventure, faces [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Daisy Miller Henry James

Daisy Miller essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Daisy Miller by Henry James.

Daisy Miller Material

- Study Guide

- Lesson Plan

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2374 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11025 literature essays, 2794 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Daisy Miller Essays

Through the eyes of the narrator: a change in perspective on daisy miller anonymous college, daisy miller.

The Novel Daisy Miller by Henry James portrays a study of an outgoing American tourist, Daisy herself, and the downfall of her reputation through the eyes of the narrator. Daisy Miller’s characterization throughout the novel is based solely on the...

At First, Second, and Third Sight: Observational Refinement in "Daisy Miller" Theoderek Wayne

He said to himself that she was too light and childish, too uncultivated and unreasoning, too provincial, to have reflected upon the ostracism or even to have perceived it. Then at other moments he believed that she carried about in her elegant...

Etiquette: A Social Ideology Joshua Lopez

Daisy Miller is a potent social commentary that considers the ideologies of transplanted Americans residing in Europe. During the late nineteenth century, the United States surfaced as a political and economic power. Wealthy Americans, anxious to...

Tracking Changes in Daisy Miller Robin Ryan

There are hundreds of differences between the 1878 edition of Daisy Miller and its 1909 / New York edition. While many of the changes are slight modifications to the placement of words or changes of some terms to an American English spelling, some...

Daisy Miller as the subject of a study, and the object of a narrative Diana Waugh

“Daisy Miller: A Study” by Henry James, a story about an American girl in Europe named Daisy Miller, is told by an unknown narrator who only has access to the main character Winterbourne’s thoughts. The story is framed around Daisy Miller and her...

The Verdict on Winterbourne in Daisy Miller Kathleen A. Cullen

Many have written about the guilt or innocence of Henry James' heroine, Daisy Miller. In her story, James tells of a young American girl in Europe who ignores Old World conventions and goes about, unchaperoned, with two gentlemen: one, an American...

Obsessions and the Unsatisfied Life: A Comparison of Daisy Miller and The Beast in the Jungle Anonymous College

In the works of Daisy Miller and The Beast in the Jungle, author Henry James provides readers with multiple explanations as to why it is important for one to live a full life. These two novellas share many broad similarities, including central...

American Illness in Daisy Miller: A Study Gabriella Calvino College

Before the revelations of modern medicine, illness of any kind was a highly mysterious and inexplicable phenomenon that was accompanied by little hope for a solution to ease or eliminate the ailment. During this time when no one knew the origin of...

Daisy's Ghost: A Feminist Reading of "Daisy Miller" Jasmine Melwing College

Daisy’s Ghost: A Feminist Reading of Daisy Miller

The novel Daisy Miller is set in the late 18th century, within high class European society. In that time period, feminism was misunderstood and even unrecognized by both genders and varying...

Storytelling in American Literature: "The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” by Mark Twain and “Daisy Miller: A Study” by Henry James as Patriotic Narratives Marissa Polodna College

Storytelling has become an important literary device found in American Literature. Stories like “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County” by Mark Twain and “Daisy Miller: A Study” by Henry James use storytelling as the simplest way promote...

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Jul 9, 2022 · Fogel, Daniel Mark. Daisy Miller: A Dark Comedy of Manners. Boston: Twayne, 1990. Graham, Kenneth. “Daisy Miller: Dynamics of an Enigma.” In New Essays on Daisy Miller and The Turn of the Screw, edited by Vivian R. Pollak, 35–63. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993. James, Henry. Daisy Miller and Other Stories.

In the story Daisy Miller, written by Henry James, James tells a story about a young American lady named Daisy Miller and her family members who are vacationing in Europe. Daisy is vacationing in a new world and is trying to find a way to learn and adapt to her new surroundings.

Jun 11, 2019 · Ultimately, all the bleakness of the world and the flaws of the characters in Daisy Miller exist to bring the story closer to the reality of the late 1800s and put that world into perspective—the perspective of a Realistic study. Works Cited. James, Henry. Daisy Miller: A Study. New York: Pearson Custom Publishing, 1878. Dallas, TX. June 2008.

Analysis Of The Misunderstandings Surrounding The Main Heroine From Henry James’ Novel Daisy Miller. 2. Literary Realism in Henry James’ Novel “Daisy Miller” 3. The Equation of Illness as a Form of Immunity in Henry James’ Daisy Miller. 4. The Character Analysis of Daisy’s Life in Daisy Miller by Henry James

We provide you with various Daisy Miller essay topics free of charge. Take your time to browse through our free samples and take notes as you make an outline. Some topics to consider include observation of sights or the social dialogue and the etiquette skills of Daisy Miller.

Feb 6, 2022 · Introduction. Henry James, a prominent figure in classic literature, left an enduring legacy with works like "Daisy Miller."In this essay, we delve into the central theme of innocence that permeates Daisy's character and the intricate ways it shapes her journey.

After returning to New York in 1905, he began to heavily revise a number of his works and to write literary introductions to them, which are considered exemplary essays in their own right. But despite his critical acclaim, approval from the general public continued to elude him, and he began to be deeply depressed.

Nov 4, 2011 · Daisy Miller – critical commentary. Story or novella? Daisy Miller represents a difficult case for making distinctions between the long short story and the novella. Henry James himself called it a ‘short chronicle’, but as a matter of fact it was rejected by the first publisher he sent it to on the grounds that it was a ‘nouvelle’ – that is, too long to be a short story, and not ...

Jun 29, 2018 · “Daisy Miller: A Study” by Henry James, a story about an American girl in Europe named Daisy Miller, is told by an unknown narrator who only has access to the main character Winterbourne’s thoughts. The story is framed around Daisy Miller and her “abnormal behavior” as the subject of Winterbourne’s study.

Daisy Miller as the subject of a study, and the object of a narrative Diana Waugh Daisy Miller “Daisy Miller: A Study” by Henry James, a story about an American girl in Europe named Daisy Miller, is told by an unknown narrator who only has access to the main character Winterbourne’s thoughts. The story is framed around Daisy Miller and her...