- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Tuskegee Experiment: The Infamous Syphilis Study

By: Elizabeth Nix

Updated: June 13, 2023 | Original: May 16, 2017

The Tuskegee experiment began in 1932, at a time when there was no known cure for syphilis, a contagious venereal disease. After being recruited by the promise of free medical care, 600 African American men in Macon County, Alabama were enrolled in the project, which aimed to study the full progression of the disease.

The participants were primarily sharecroppers, and many had never before visited a doctor. Doctors from the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS), which was running the study, informed the participants—399 men with latent syphilis and a control group of 201 others who were free of the disease—they were being treated for bad blood, a term commonly used in the area at the time to refer to a variety of ailments.

The men were monitored by health workers but only given placebos such as aspirin and mineral supplements, despite the fact that penicillin became the recommended treatment for syphilis in 1947, some 15 years into the study. PHS researchers convinced local physicians in Macon County not to treat the participants, and instead, research was done at the Tuskegee Institute. (Now called Tuskegee University, the school was founded in 1881 with Booker T. Washington as its first teacher.)

In order to track the disease’s full progression, researchers provided no effective care as the men died, went blind or insane or experienced other severe health problems due to their untreated syphilis.

In the mid-1960s, a PHS venereal disease investigator in San Francisco named Peter Buxton found out about the Tuskegee study and expressed his concerns to his superiors that it was unethical. In response, PHS officials formed a committee to review the study but ultimately opted to continue it—with the goal of tracking the participants until all had died, autopsies were performed and the project data could be analyzed.

Buxton then leaked the story to a reporter friend, who passed it on to a fellow reporter, Jean Heller of the Associated Press. Heller broke the story in July 1972, prompting public outrage and forcing the study to finally shut down.

By that time, 28 participants had perished from syphilis, 100 more had passed away from related complications, at least 40 spouses had been diagnosed with it and the disease had been passed to 19 children at birth.

In 1973, Congress held hearings on the Tuskegee experiments, and the following year the study’s surviving participants, along with the heirs of those who died, received a $10 million out-of-court settlement. Additionally, new guidelines were issued to protect human subjects in U.S. government-funded research projects.

As a result of the Tuskegee experiment, many African Americans developed a lingering, deep mistrust of public health officials and vaccines. In part to foster racial healing, President Bill Clinton issued a 1997 apology, stating, “The United States government did something that was wrong—deeply, profoundly, morally wrong… It is not only in remembering that shameful past that we can make amends and repair our nation, but it is in remembering that past that we can build a better present and a better future.”

During his apology, Clinton announced plans for the establishment of Tuskegee University’s National Center for Bioethics in Research and Health Care .

The final study participant passed away in 2004.

Tuskegee wasn't the only unethical syphilis study. In 2010, then- President Barack Obama and other federal officials apologized for another U.S.-sponsored experiment, conducted decades earlier in Guatemala. In that study, from 1946 to 1948, nearly 700 men and women—prisoners, soldiers and mental patients—were intentionally infected with syphilis (hundreds more people were exposed to other sexually transmitted diseases as part of the study) without their knowledge or consent.

The purpose of the study was to determine whether penicillin could prevent, not just cure, syphilis infection. Some of those who became infected never received medical treatment. The results of the study, which took place with the cooperation of Guatemalan government officials, were never published. The American public health researcher in charge of the project, Dr. John Cutler, went on to become a lead researcher in the Tuskegee experiments.

Following Cutler’s death in 2003, historian Susan Reverby uncovered the records of the Guatemala experiments while doing research related to the Tuskegee study. She shared her findings with U.S. government officials in 2010. Soon afterward, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Secretary of Health and Human Services Kathleen Sebelius issued an apology for the STD study and President Obama called the Guatemalan president to apologize for the experiments.

How an Enslaved African Man in Boston Helped Save Generations from Smallpox

In the early 1700s, Onesimus shared a revolutionary way to prevent smallpox.

7 of the Most Outrageous Medical Treatments in History

Why were parents giving their children heroin in the 1880s?

The ‘Father of Modern Gynecology’ Performed Shocking Experiments on Enslaved Women

His use of Black bodies as medical test subjects falls into a history that includes the Tuskegee syphilis experiment and Henrietta Lacks.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Remembering the man who blew the whistle on the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

The Associated Press is finishing up 2025 by remembering notable newsmakers who died this year. One may be familiar to longtime listeners to Alabama Public Radio. Pete Buxton died in May at the age of eighty six. He was the federal health care worker who blew the whistle on the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment. Buxton spoke with APR about what happened when doctors tried to treat black men deliberately infected with the disease..

“The doctor who did the right thing had the medical society and the county health authorities jump down his throat. Look what you've done,” said Buxton. “You've treated one of these guys, you're not supposed to treat them. If he had had, let's say, pneumonia, there would have been a procedure to go through some paperwork to get permission to save the guy's life. For Christ's sake.”

Buxton’s comments were part of APR investigation that won the fiftieth annual Robert F. Kennedy Journalism Award for Radio. Our coverage of the Tuskegee Syphilis experiment was at a twentieth anniversary observance of President Bill Clinton’s apology for what happened. APR reported how, in 1972 Buxton tipped off a reporter from the Associated Press, and the story soon broke.

“The men started out wanting just for me to sell their lawsuit and get an apology,” said attorney Fred Gray before Tuskegee. His client list included civil rights icon Rosa Parks.

"And, they wanted a permanent memorial here. What was done cannot be undone, but we can end the silence,” he said.

Gray sued. The government settled, and in 1997 President Clinton gave the subjects of the Tuskegee syphilis study the words they wanted to hear.

“What the United States government did was shameful, and I am sorry,” the President said.

- Academic Calendar

- Campus Directory

- Campus Labs

- Course Catalog

- Events Calendar

- Golden Tiger Gear

- Golden Tiger Network

- NAVIGATE 360

Quick Links

- Academic Affairs - Provost

- ADA 504 Accommodations - Accessibility

- Administration

- Advancement and Development

- Air Force ROTC

- Alumni & Friends

- Anonymous Reporting

- Bioethics Center

- Board of Trustees

- Campus Tours

- Career Center

- Colleges & Schools

- COVID-19 Updates

- Dean of Students and Student Conduct

- E-Learning (ODEOL)

- Environmental Health & Safety

- Facilities Services Requests

- Faculty Senate

- Financial Aid

- General Counsel and External Affairs

- Graduate School

- HEERF - CARES Act Emergency Funds

- Housing and Residence Life

- Human Resources

- Information Technology

- Institutional Effectiveness

- Integrative Biosciences

- Office of the President

- Online Degree Admissions

- Parent Portal (Family & Parent Relations)

- Police Department - TU

- Research and Sponsored Programs

- ROTC at Tuskegee University

- Staff Senate

- Strategic Plan

- Student Affairs

- Student Complaints

- Student Handbook

- Student Health Center

- Student Life and Development

- Tuskegee Scholarly Publications

- Tuition and Fees

- Tuskegee University Global Office

- TU Help Desk Service Portal

- TU Office of Undergraduate Research

- University Audit and Risk Management

- Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory Services

- Visitor Request Form

Tuskegee University

- Board Meeting Dates

- Current Trustees

About the USPHS Syphilis Study

Where the Study Took Place

The study took place in Macon County, Alabama, the county seat of Tuskegee referred to as the "Black Belt" because of its rich soil and vast number of black sharecroppers who were the economic backbone of the region. The research itself took place on the campus of Tuskegee Institute.

What it Was Designed to Find Out

The intent of the study was to record the natural history of syphilis in Black people. The study was called the "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male." When the study was initiated there were no proven treatments for the disease. Researchers told the men participating in the study that they were to be treated for "bad blood." This term was used locally by people to describe a host of diagnosable ailments including but not limited to anemia, fatigue, and syphilis.

Who Were the Participants

A total of 600 men were enrolled in the study. Of this group 399, who had syphilis were a part of the experimental group and 201 were control subjects. Most of the men were poor and illiterate sharecroppers from the county.

What the Men Received in Exchange for Participation

The men were offered what most Negroes could only dream of in terms of medical care and survivors insurance. They were enticed and enrolled in the study with incentives including: medical exams, rides to and from the clinics, meals on examination days, free treatment for minor ailments and guarantees that provisions would be made after their deaths in terms of burial stipends paid to their survivors.

Treatment Withheld

There were no proven treatments for syphilis when the study began. When penicillin became the standard treatment for the disease in 1947 the medicine was withheld as a part of the treatment for both the experimental group and control group.

How/Why the Study Ended

On July 25, 1972 Jean Heller of the Associated Press broke the story that appeared simultaneously both in New York and Washington, that there had been a 40-year nontherapeutic experiment called "a study" on the effects of untreated syphilis on Black men in the rural south.

Between the start of the study in 1932 and 1947, the date when penicillin was determined as a cure for the disease, dozens of men had died and their wives, children and untold number of others had been infected. This set into motion international public outcry and a series of actions initiated by U.S. federal agencies. The Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs appointed an Ad Hoc Advisory Panel, comprised of nine members from the fields of health administration, medicine, law, religion, education, etc. to review the study.

While the panel concluded that the men participated in the study freely, agreeing to the examinations and treatments, there was evidence that scientific research protocol routinely applied to human subjects was either ignored or deeply flawed to ensure the safety and well-being of the men involved. Specifically, the men were never told about or offered the research procedure called informed consent. Researchers had not informed the men of the actual name of the study, i.e. "Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male," its purpose, and potential consequences of the treatment or non-treatment that they would receive during the study. The men never knew of the debilitating and life threatening consequences of the treatments they were to receive, the impact on their wives, girlfriends, and children they may have conceived once involved in the research. The panel also concluded that there were no choices given to the participants to quit the study when penicillin became available as a treatment and cure for syphilis.

Reviewing the results of the research the panel concluded that the study was "ethically unjustified." The panel articulated all of the above findings in October of 1972 and then one month later the Assistant Secretary for Health and Scientific Affairs officially declared the end of the Tuskegee Study.

Class-Action Suit

In the summer of 1973, Attorney Fred Gray filed a class-action suit on behalf of the men in the study, their wives, children and families. It ended a settlement giving more than $9 million to the study participants.

The Role of the US Public Health Service

In the beginning of the 20th Century, the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) was entrusted with the responsibility to monitor, identify trends in the heath of the citizenry, and develop interventions to treat disease, ailments and negative trends adversely impacting the health and wellness of Americans. It was organized into sections and divisions including one devoted to venereal diseases. All sections of the PHS conducted scientific research involving human beings. The research standards were for their times adequate, by comparison to today's standards dramatically different and influenced by the professional and personal biases of the people leading the PHS. Scientists believed that few people outside of the scientific community could comprehend the complexities of research from the nature of the scientific experiments to the consent involved in becoming a research subject. These sentiments were particularly true about the poor and uneducated Black community.

The PHS began working with Tuskegee Institute in 1932 to study hundreds of black men with syphilis from Macon County, Alabama.

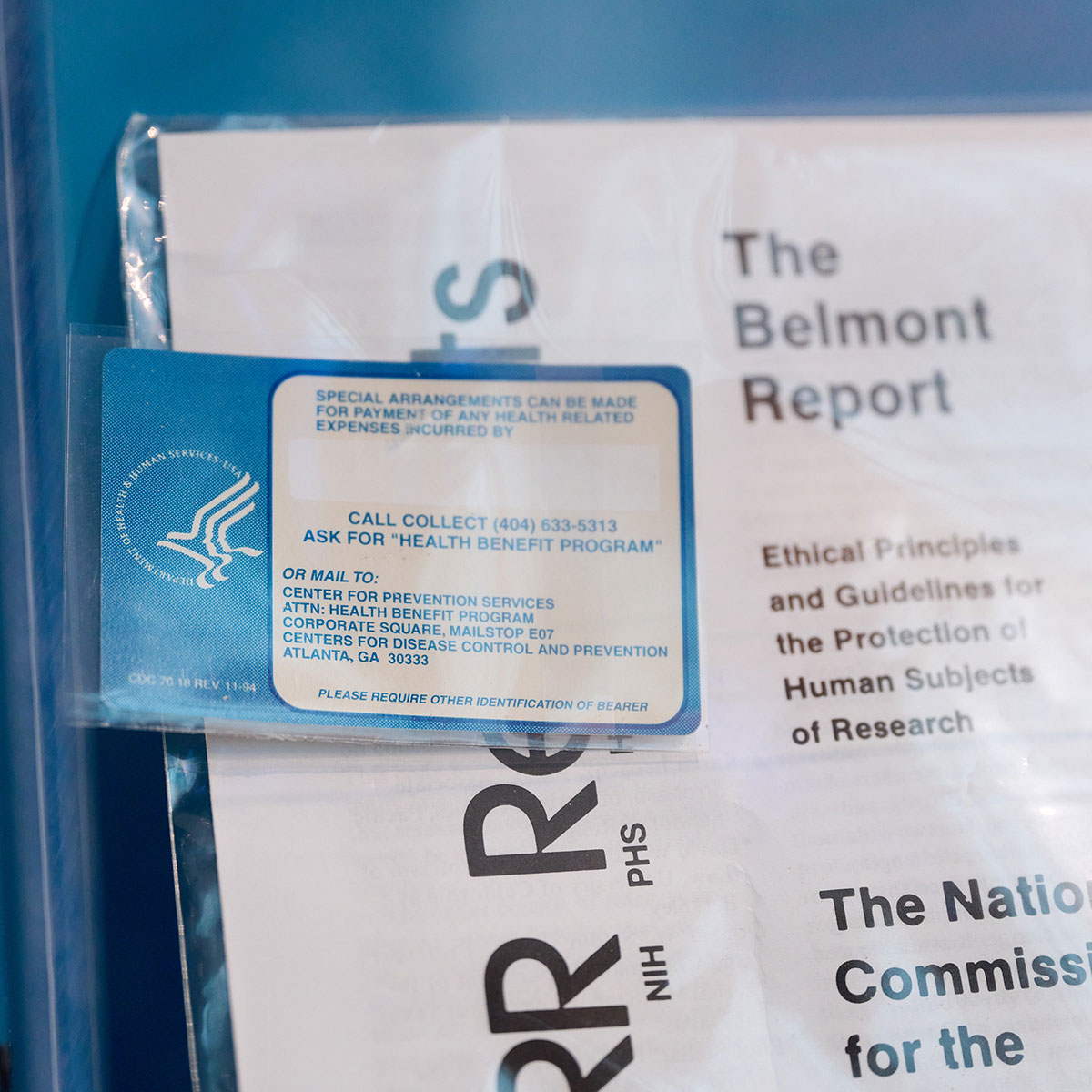

Compensation for Participants

As part of the class-action suit settlement, the U.S. government promised to provide a range of free services to the survivors of the study, their wives, widows, and children. All living participants became immediately entitled to free medical and burial services. These services were provided by the Tuskegee Health Benefit Program, which was and continues to be administered by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in their National Center for HIV, STD and TB Prevention.

1996 Tuskegee Legacy Committee

In February of 1994 at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library in Charlottesville, VA, a symposium was held entitled "Doing Bad in the Name of Good?: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study and Its Legacy." Resulting from this gathering was the creation of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study Legacy Committee which met for the first time in January 18th & 19th of 1996. The committee had two goals; (1) to persuade President Clinton to apologize on behalf of the government for the atrocities of the study and (2) to develop a strategy to address the damages of the study to the psyche of African-Americans and others about the ethical behavior of government-led research; rebuilding the reputation of Tuskegee through public education about the study, developing a clearinghouse on the ethics of scientific research and scholarship and assembling training programs for health care providers. After intensive discussions, the Committee's final report in May of 1996 urged President Clinton to apologize for the emotional, medical, research and psychological damage of the study. On May 16th at a White House ceremony attended by the men, members of the Legacy Committee and others representing the medical and research communities, the apology was delivered to the surviving participants of the study and families of the deceased.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Say Their Names

- Green Library Exhibit

- 3 T's (Systemic Racism)

Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment

The official title was “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male.” It is commonly called the Infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Beginning in 1932 and continuing to 1972 the United States Public Health Services lured over 600 Black men, mostly sharecroppers in Tuskegee, Alabama, into this diabolical medical experiment with the promise of free health care. For 40 years, hundreds of African American men with syphilis went untreated, given placebos and other ineffective treatments, so that scientists could study the effects of the disease, even after there was a cure. None of the men who had syphilis were ever told they had it. Instead they were only told that they had “bad blood.” They were also never given penicillin, despite the fact that it had become a standard treatment by 1947.

The last survivor of the study died in 2004. This was not that long ago.

The Hippocratic Oath is used as a symbolic gesture that binds physicians to their patient’s well-being. Those who choose to take the oath makes an affirmation about treatment of those entrusted in their care, “I will do no harm or injustice to them.” It is commonly simply rephrased as, "First, do no harm." That was not the case with healthcare providers in Tuskegee, AL.

Below is an excerpt from an official admission of systematic racial discrimination issued by the United States President in 1997:

The President’s words confirmed the institutionally and racially discriminatory practices that have spanned not just decades as in this case, but centuries. Medical malfeasance is nothing new. Currently, amends are being made symbolically. In 2018, New York City finally removed an offensive statue from high atop a pedestal in Central Park. The statue depicted an infamous 19th-century gynecologist who experimented on enslaved women named Anarcha, Lucy and Betsey. He was part of a medical apartheid system that treated Black subjects as sub-human. He inflicted unimaginable torture because he operated under the ridiculous notion that Black people did not feel pain.

Remarkably, present day studies reveal that a frightening number of healthcare providers believe the myth that Black people have thicker skin and therefore need less pain management. The University of Virginia reported that racial bias partially explains research documenting how Black Americans are systemically undertreated for pain.

The Tuskegee Experiment was relatively recent and at least partially impacts the reactions to the current Novel Coronavirus pandemic. Black Americans have this recent example, in addition to a long history of other examples, explaining why it is reasonable to be suspicious of governmental medical information.

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis at Tuskegee and Macon County, AL

In 1932, 399 African American men in Tuskegee and Macon County, Alabama were enrolled in a Public Health Service study on the long-term effects of untreated syphilis . At that time, there was no cure for syphilis, though many ineffective and often harmful treatments, such as arsenic, were used. In the 1940s, penicillin was discovered, and by the 1950s, it was widely accepted by the medical community as the quickest and most effective treatment for syphilis . The men in the study were not made aware of the availability of penicillin as treatment, however, and the study continued and was transferred to CDC along with the PHS VD Unit in 1957.

The study was intended to last only six months but continued into the 1970s. In 1968, Peter Buxton, a CDC Public Health Advisor in the USPHS, raised questions about the study. After several years of questioning by Mr. Buxton, several news articles were published, leading to a Senate investigation headed by Sen. Edward Kennedy. It was this investigation that forced the study’s end in 1972. CDC and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) acknowledged the study as unethical, ended it, and compensated study survivors for medical care and burial expenses.

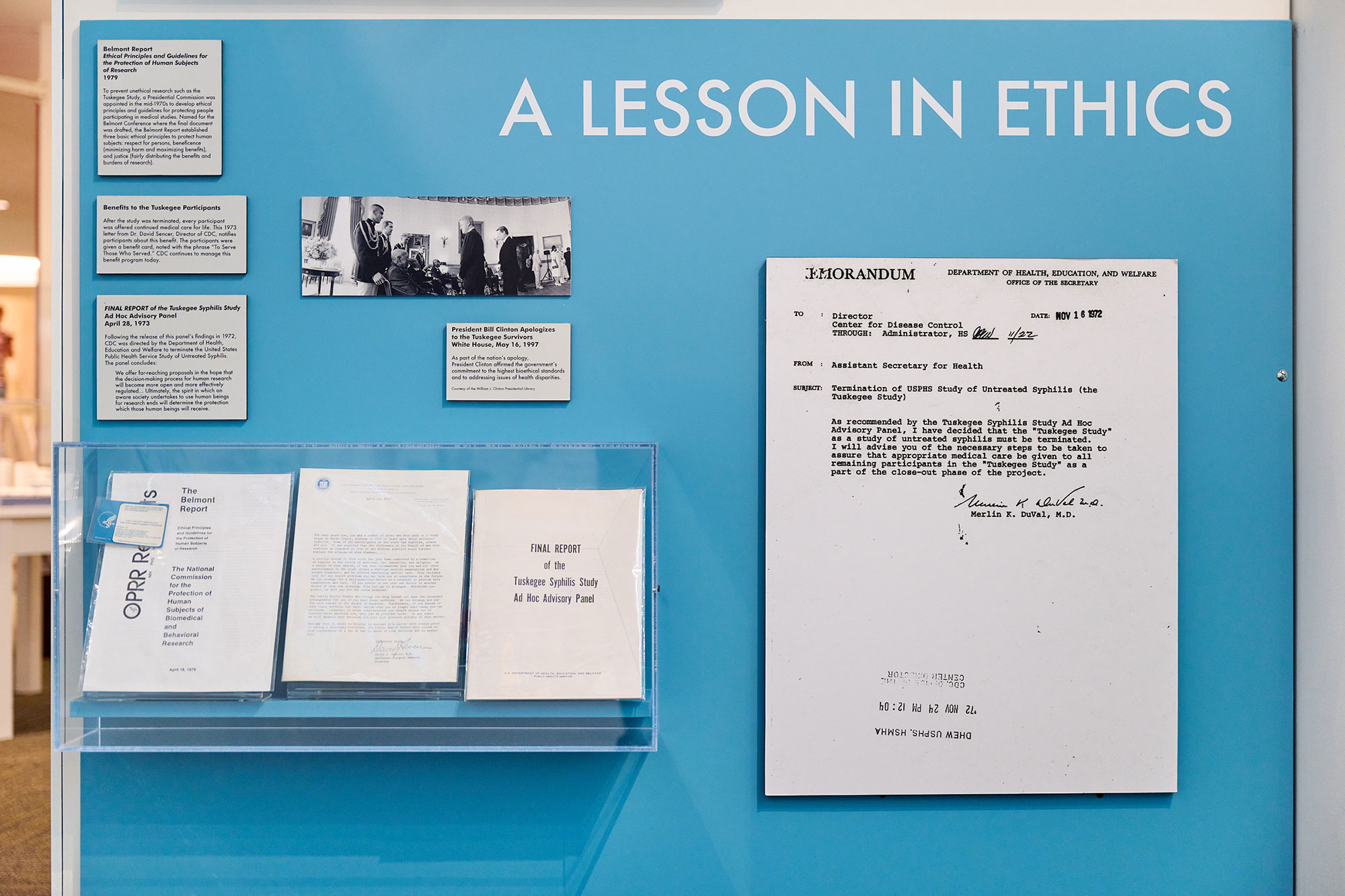

Shown above is a letter that then-CDC Director Dr. David J. Sencer wrote to the survivors of the U.S. Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis at Tuskegee and Macon County, AL explaining that they would receive medical care for the rest of their lives. Also on display is one of the benefits cards that was distributed, which reads, “To Serve Those Who Served,” as well as a photograph of President Clinton with the survivors at the White House, where on May 16th, 1997, he officially apologized to the last living participants.

Out of this tragedy came the Belmont Report , a comprehensive document that created new standards of research to protect participants from unethical practices.

For more information, including the names of the men in the study, please visit Voices for Our Fathers Legacy Foundation (voicesforfathers.org) and Tuskegee Study and Health Benefit Program – CDC – OS .

Take a closer look:

- What is syphilis and how does it spread? Learn more about syphilis and the bacterium that causes the disease, Treponema pallidum .

- View a close-up image of Treponema pallidum under a microscope and grimace at symptoms of syphilis symptoms on a human hand .

- Learn more about gonorrhea and the bacterium that causes it, Neisseria gonorrhoeae .

- Explore CDC’s STD resources covering prevention initiatives, surveillance, treatment, training programs, and so much more.

- Did you know human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S.? Learn more in this CDC Museum Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter .

From the source:

- Meet Brandy Maddox , Health Scientist in the Division of Sexually Transmitted Disease Prevention at CDC.

- Hear from a CDC expert about her path to public health and her work in adolescent sexual health at CDC in the CDC Museum Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter: September 2020 – Healthy Schools Zoom .

- Keep up with the latest STD updates from CDC on Twitter and Facebook .

- Did you know that there is a vaccine to protect against some strains of HPV that cause cancer? Learn more from the cervical cancer survivor in this video .

- Listen to CDC experts talk about their paths to public health and their work with human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States in the CDC Museum Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter: January 2021 – HPV Zoom .

Then and now:

- Learn more about incidence, prevalence, and cost of STIs over time in the U.S.

- Read about CDC’s STD prevention success stories .

- View a timeline of the Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee and learn how this study informed ethical data collection and changed research practices for good.

- Explore the history of traveling and sexually transmitted diseases in this EID issue .

- Learn about preventing antibiotic-resistant gonorrhea and CDC measures to combat antibiotic resistance across the U.S.

- Contemplate the impact of the Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee on affected families .

- Read about nurse Eunice Rivers , the nurse who worked on the Tuskegee Study.

Give it a try:

- A Public Health Advisor (PHA) conducts a contract tracing investigation [572 KB, 1 Page]

- A Public Health Advisor (PHA) dons gear to conduct contact tracing in the community [459 KB, 1 Page]

- A patient shows symptoms to a PHA in order to be diagnosed and treated [206 KB, 1 Page]

- How does contract tracing work? Find CDC contact tracing guidance and resources .

- 3D print a model of a portion of human papillomavirus through the National Institutes of Health 3D Print Exchange .

- Looking to expand your knowledge on STDs? Check out these continuing education resources .

- Know your status. Find a testing site near you.

- Take a deep dive into human papillomavirus (HPV), the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States in the CDC Museum Public Health Academy Teen Newsletter: January 2021 – HPV .

- Request a Speaker

- CDC History

- Smithsonian Institution

- CDC Museum Brochure [8.8 MB, 2 Pages, 16″ x 9″]

- CDC Museum Press Sheet [2.3 MB, 1 page]

Monday: 9am-5pm Tuesday: 9am-5pm Wednesday: 9am-5pm Thursday: 9am-7pm Friday: 9am-5pm Closed weekends & federal holidays

Always Free Government–issued photo ID required for adults over the age of 18 Passport required for non-U.S. citizens

- Weapons are prohibited. All vehicles will be inspected.

1600 Clifton Road NE Atlanta, GA 30329

404-639-0830

To receive email updates about this page, enter your email address: